This is the 100th birth anniversary of Mrinal Sen, a revered icon of Indian political cinema. Mrinal Sen was born on 14 May 1923 in present-day Faridpur, Bangladesh. He died in Kolkata at the age of 95. In the meantime, that genius brought Bengali cinema to the stage of world cinema. He has received state government awards, national awards, to international recognition. He was felicitated at film festivals like Berlin, Cannes, Moscow, and Karlovy Vary and was honored by the French and Russian governments.

Research and experiments in the cinematic medium already existed before the Lumiere brothers screened the world’s first film. Apart from the French inventors, many people displayed the archetypes of cinema. The camera obscura, bioscope, and kinetoscope were the attempts before the successful film screening of the Lumière brothers. In 1891, Edison’s company successfully tested the kinetoscope and brought it to market. The earlier short films of the Lumière brothers can be seen as the ultimate success of many such attempts.

As cinema started developing as an art form and capturing the market, it also became politically divided. Talents like Griffith propagated racism by lionizing white supremacists. At the same time, filmmakers Oscar Micheaux, William D. Foster, Emmet J. Scott, Noble Johnson, etc., waged a war of social resistance against malevolent white nationalism. In fact, Black cinema was not only a film of resistance but also of survival. These films give us a picture of self-realization and self-empowerment of people who have been subjugated for centuries and are still helpless with all kinds of ridicule for being black.

Later on in the film, there were two sides. Oppressors and combatants. Most of the commercial films we see propagate the oppressors’ ideology. All of them are politically anti-people. The films many look down on as political films were also films of struggle. These stood by the side of all humans fighting across continents. Wherever people struggle for freedom and equality, films have explored the politics behind it. In Latin America, Eastern Europe, Iran, and Turkey, such films have appeared wherever people struggled under the oppressive, authoritative Nation-State.

Ousmane Sembène in Senegal, Youssef Chahine in Egypt, Oumarou Ganda in Nigeria, Jean-Pierre Dikongué Pipa in Cameroon, Carlos Zora in Spain, Fernando Solanos in Argentina, Mohamed Lakhdar Hamina in Algeria and that line can be extended to any length. Such reflection of sociopolitical struggles in cinema continues in contemporary society, too—Jafar Panahi in Iran, Ken Loach in the UK, and Costa Gavres in Greece. Many directors from India joined in that struggle. However, Mrinal Sen was the most prominent among them.

Mrinal Sen is a genius who politicized not only Bengali cinema but Indian cinema as well. He is the director who showed Indians what real political cinema is. In his book on Mrinal Sen, Soumik Kanti Ghosh writes that political films depict the conflicts between those governing and the governed. It indicates how the media, leaders, voters, etc., should respond to national and international events. In this sense, Sen has expressed his opinions through his films on all of Bengal and India’s contemporary political and social issues, which directly or indirectly affect the people. All of them perceived the monumental human struggles from the side of the oppressed.

Most people think of Satyajit Ray when they hear Bengali cinema. He was hailed as an apostle of Indian cinema. He is internationally known as an icon of Indian cinema. But Ray’s films are not overtly political. Even in the 70s, when anarchy and chaos were unleashed, Ray embarked on a cinematic journey that’s less politically critical. Ray mostly depicted the personal experiences of ordinary people, although the poverty shown in his films can be felt as a sin of birth.

Even the poverty shown in the Apu Trilogy was a mere showcase piece. In films like Jalsagar, Ray portrayed the psychological conflicts and sense of injustice of upper-class life that lost its power. Ray’s only consideration was the poetic language of the film. Through it, he carefully presented the psychological anguish of the man on the screen. They were all great movies. Starvation, exploitation, and oppression appear in Ray’s films, but they do not become a political experience.

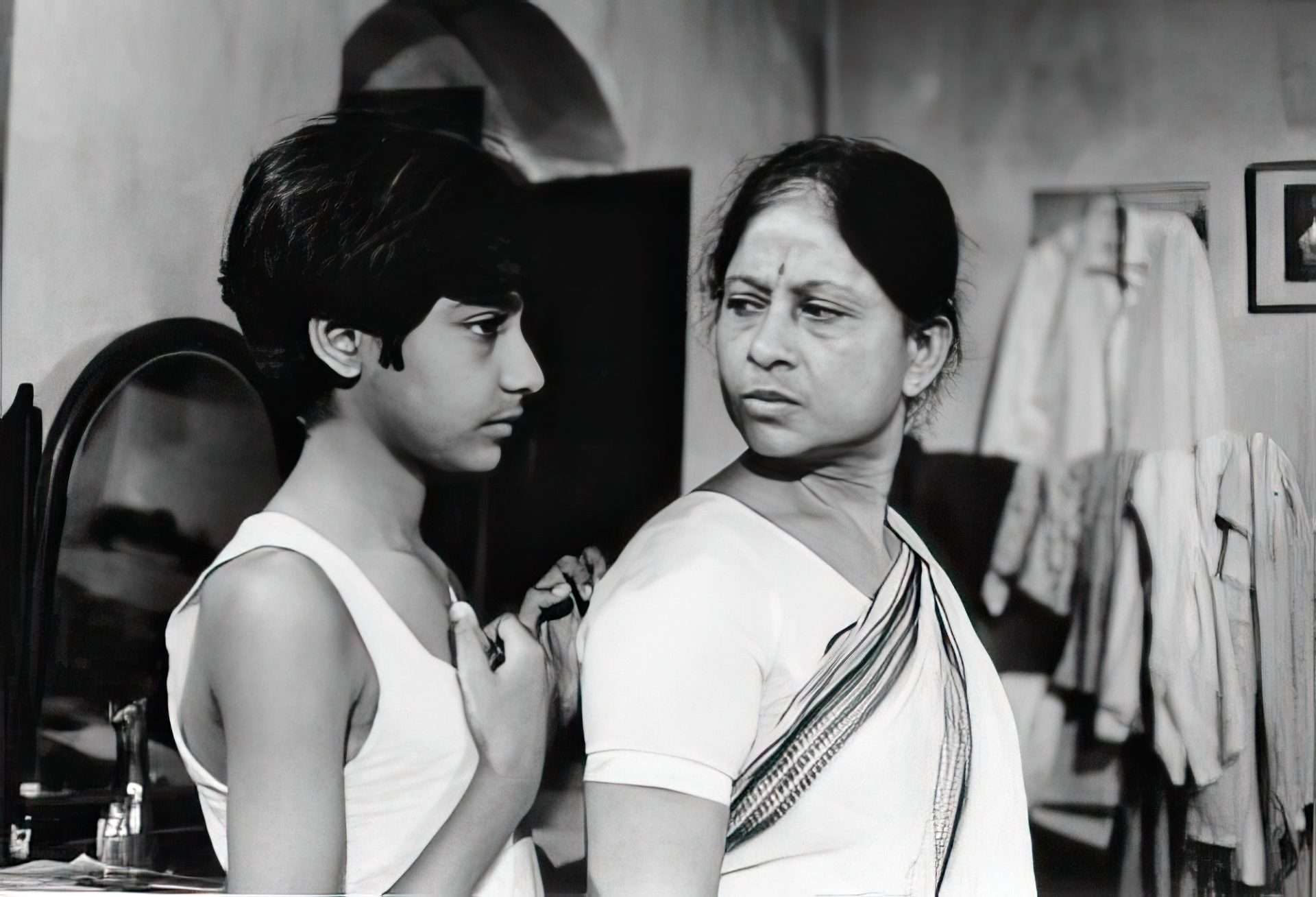

But Mrinal Sen is entirely different from this. Sen’s camera roamed the streets and slums of Calcutta and the cramped homes of the oppressed in search of human struggles for survival. In films such as Interview, Calcutta 71, Chalchitra, and Mrigaya, he presented a vivid picture of human efforts for survival. In his films, he tore off the mask of an Indian who hesitated to get rid of foreign culture even after years of independence. It’s the theme he tackles in the interview.

The film revolves around the problems of a young man working in an ordinary newspaper who is willing to attend an interview for a better job. His uncle tells him to attend the interview wearing a foreign suit, coat, and tie. But his coat and suit got stuck in the laundry, so he had to borrow them. But he could not keep even the borrowed suit. So he was forced to appear dressed in traditional Bengali attire for the interview.

Sen exposes the Indian who, despite his political independence, remains mentally enslaved to foreigners. Even today, the social respect accorded to English speakers suggests that Sen’s cinema has not lost its relevance to date. It should also be remembered that the hero of ‘Interview’ was not self-centered. He reacts to all the fundamental problems of the society in which he lives, even if it endangers his own life. It is during one such interaction that he loses his borrowed coat. The Interview is the first film in Mrinal Sen’s famous Calcutta trilogy.

It was followed by “Calcutta 71” and “Padatik.” Calcutta 71 is an anthology of multiple stories. The movie’s plot is about the poverty and exploitation faced by the ordinary people of Calcutta. Sen depicts the lives of ‘enslaved’ human beings, unable to protest and react. The influence of Italian neorealist films is evident in Sen’s films. We can see that most of his movies are set in the middle-class residences of Kolkata. Sen captures the life experiences of the people who suffer the hell of life in these shelters and are often unresponsive. Sen is transplanting De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves and Fellini’s La Strada to the Indian environment.

Though Sen was a fervent ideologue when it came to politics, he also tried to criticize the flaws in the ideology he supported. In Padatik, Sen critically examines the Naxalbari movement of the 70s. Sen questions the political ethos of the Naxalbari movement through a young revolutionary who escapes from police custody and lives in a hideout set up by the party. Padatik is a movie that created a lot of buzz.

Both left and right attacked the film. Padatik is still discussed as one of Sen’s most essential films. Through the movie “Bhuvan Shome,” Sen says that no matter how honest a person is, he can walk on the wrong path without realizing it. The protagonist was honest and strict. The movie ends with him insisting that things should be done correctly without compromise, but he eventually and unwittingly joins the circle of corruption. Moreover, Bhuvan Shome (1969) is a film that beautifully portrays the simplicity of rural life.

Sen often sees and chooses themes that others hesitate to visit. All of them will be replicas of the everyday miseries of common people in Calcutta. Chalchitra (The Kaleidoscope, 1981) deals with one such theme. Coal stoves were the most fundamental problem of Calcutta’s housewives. These coal stoves were used in hundreds of homes, and smoke from these coal stoves was one of the critical health problems faced by middle-class households. But no one took this issue seriously.

By doing so, Sen brought to the public’s attention a fundamental problem experienced by all homemakers in a city. The consternation created by the sudden disappearance of individuals is beyond our imagination. While ‘Ek Din Achanak’ deals with the sudden disappearance of a person from a family, ‘Ek Din Pratidin’ deals with the non-arrival of a girl who is the family’s only breadwinner.

The theme of Ek din Achanak is that the surprise of the head of the family suddenly disappears one day, and the family gradually forgets his absence. The story of Ek Din Pratidin is that the eldest daughter was late coming home one day from work which caused a disturbance in the family and neighbors.

Everything calms down when the girl returns. Beyond telling us that time can overcome the disappearance of even our most loved ones, Sen tells us how even the temporary departure of each person can endanger the lives of their loved ones. And that there are no wounds that time does not erase.

Actor Dritiman Chatterjee shares his experience of visiting Sen during his last days. At that time, Sen was oscillating between memory and oblivion. At one point in his memory, Dritiman told Sen that he had acted in Sen’s film. Then, from unconsciousness, Sen suddenly asked, “Who is the cameraman of that movie?” Dritiman Chatterjee says that only a true movie lover would ask such a question.

Mrinal Sen was primarily a radical and innovative filmmaker. Mrinal Sen’s explosive works remind us how much the director elegantly blended Indian socio-political issues and cinema.

Read More:

The 10 Best Indian Films of All Time As Chosen By FIPRESCI-INDIA

50 Years of Nirmalyam (1973): Timeless, Introspective, and Radical

Raj Kapoor – Director’s Study