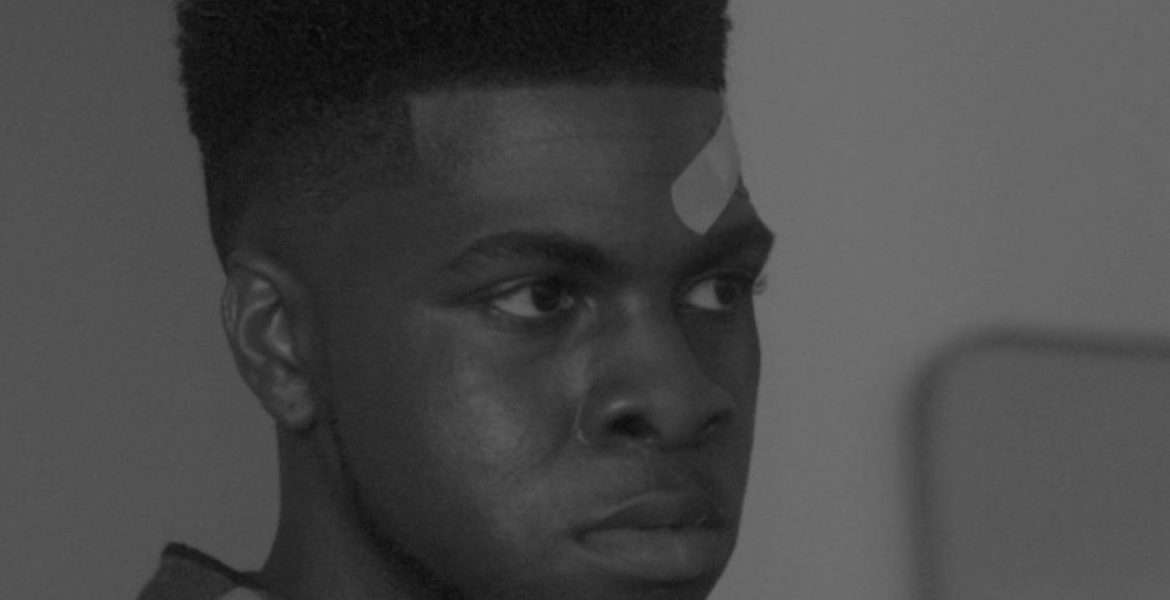

The story of Mickey Hardaway begins in media res. We follow the character (played by Rashad Hunter) as he breaks into a house and murders an unsuspecting victim, shooting a gun that we never hear go off. The film then cuts immediately to about three weeks prior without warning, as Mickey’s girlfriend Grace (Ashley Parchment) urges him to speak to a therapist about his troubles. The troubled artist acquiesces, and this is where the crisscrossing structure of Mickey Hardaway takes root. Written and directed by Marcellus Cox, this heartfelt drama about the cycles of trauma in black communities is very well-acted but held back by a clumsy, contrivance-prone script.

The titular Hardaway is a gifted artist born in an unforgiving household. His father, Randall (David Chattam), is abusive, carrying on the traditions of violence established by his forebears and embittered by his own victimization. Mickey’s mother (Gayla Johnson) is more sincere but powerless to stop her husband from striking their children. As Mickey leaves school and attempts to strike out on his own, he realizes that life as an artist is more challenging than he thought it would be, taking a toll on his health and revealing how black talent is exoticized and taken advantage of.

Cox and editor Jamil Gooding structure the film like a nesting doll, revealing layers of Mickey’s story in discrete sequences that incorporate flashbacks-within-flashbacks. The weekly therapy sessions serve as a neat framing device, functioning as bookends for each of the film’s three acts. The overall design of the plot is very methodical, covering the crests and troughs of a traditional three-act screenplay with great precision. Alas, the content of those acts feels earnest at best, manipulative at worst, wringing drama in a way that feels forced and overly miserable. But while the film certainly puts a lot of pressure on its protagonist, it punishes him most by painting him with that tired cliche: the tortured artist.

The film’s first act is quite powerful, covering Mickey’s transition from student to professional cartoonist. It features powerful performances from Hunter, Chattam, and Johnson and charming turns by actors Blake Hezekiah and Christopher M. Cook as younger Mickey and the older brother, respectively. Driven by said acting, this first section gives us a great sense of the character’s upbringing. Gifted in sketches and hand-drawn art from a young age, Mickey is discouraged from pursuing his dreams by his deadbeat dad. There is a bitterness inherent to the dynamic between father and son here that will be familiar to most artists with non-artistic backgrounds, and it is beautifully brought to life by the performances.

Unfortunately for the actors, the script here does not do much to support the work on display. The writing here is plagued by some very flimsy dialogue and tired platitudes. It’s a testament to the strength of the cast that formulaic lines like “Art is a waste of time. It’s not a liveable career” land with any amount of emotion whatsoever. When Mickey’s therapist asks him what his problem is, and Mickey replies with “Life. Life is the issue,” we sympathize with him because of the humanity in Hunter’s eyes, so soulful that they are able to enliven even the most wooden of dialogue. And Mickey Hunter, unfortunately, has plenty of that.

Up until the end of the first therapy session, that is not too much of a problem. During the rise and fall of the second act, the more forced elements of the script rear their heads. This begins with the introduction of Nathan Hammerson (Samuel Whitehill), a head writer at a local press firm where Mickey applies for work. This character is obviously villainous from his very first scene, attempting to sweet-talk our main character into devious deals. By introducing his first (and practically only) white character in this way, Cox makes his point with unnecessary bluntness.

Hammerson talks about Mickey’s work like it’s the most incredible thing he’s ever seen and emphasizes that Mickey is a big part of that. “You’re one of a kind,” he tells the young boy, and even Mickey finds this hard to believe. Cox’s point here appears to be that black artists are exoticized and treated as precious and different instead of simply being allowed to exist–a fine theme to explore. Unfortunately, this scene hammers home this form of intrinsic racism mercilessly; Mickey even comments on Hammerson’s superlatively praise some four times in the same sequence, and it doesn’t help that Whitehill’s expressions resemble the face of the man in “Hide the Pain Harold.” At this point, the film takes a turn for the worse.

Cox’s script can’t resist rubbing every single theme on its mind into the viewer’s mind, and this detracts from the film’s many strong suits: the capable direction, the sincere performances, and the beautiful cinematography (also by Jamil Gooding). The monochromatic imagery is gorgeous and serves a purpose beyond aesthetics. As much as we would like to pretend that stories of black criminals are black and white in nature, they are anything but. Gooding and Cox utilize this irony to significant effect, and it’s one of the subtler features of the film’s craft that makes an impression. There’s also a lovely sequence halfway through the picture where Gooding proves he is just as capable of shooting in color as he is in monochrome. The imagery in the film is well-composed and mature.

Also commendable is the love story between Mickey and Grace; Hunter and Parchment have excellent chemistry (though their first conversation obviously took place in a different location in the script–why would someone say, “If you like that phone so much, why don’t you put a ring on it?” to a stranger at a public park?). Their pairing feels like a missed opportunity, as Mickey Hardaway is too intent on meaning something to commit to a more fleshed-out portrayal of this intriguing relationship.

Ultimately, while the technical aspects of the production are commendable, the ultimate trajectory of the plot pulls the viewer away from appreciating them. The drama in Mickey Hardaway is unfortunately contrived–there is no texture to its world beyond the idea of the suffering of black artists. In a climactic conversation that spells out the movie’s themes, Cox suggests that society is to blame for the victimization of these young individuals. The observation is pat, so obvious that it feels insulting. Mickey Hardaway has other insights to share, but it ends where it does feel uninspired and defeatist.