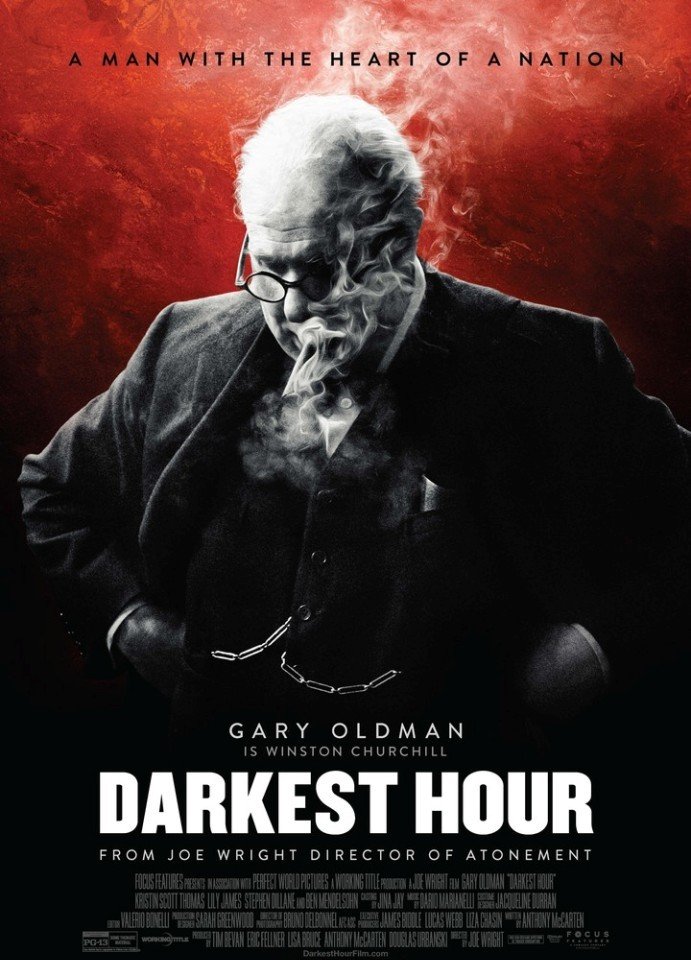

Darkest Hour [2017]: A Decent Historical Drama Powered by First-Rate Cast

Joe Wright’s Darkest Hour (2017), similar to Steven Spielberg’s mesmerizingly nuanced Lincoln (2012), adopts a narrative structure that makes it less of a biopic about a great political leader, and more of a gritty historical drama which tries to encapsulate the specific leader’s personality over the course of a single, momentous event. Darkest Hour offers an engaging take on the inner workings of British government in spring 1940, the crucial period that saw Britain’s controversial and charismatic leader Winston Churchill’s ascension as Prime Minister and later his famous call-to-arms speech, when Adolf Hitler’s military forced seemed unstoppable. Looking back at the Allied victory of World War II, it seems like fighting against Nazi menace was the only possible decision left to English statesmen. However, in reality, the Nazi threat was soaring high enough to make the reasonable English statesmen of 1940 to actually consider a truce and open negotiations with Hitler. While his close-circle of advisors, despite their hatred for Hitler sought for peace at ‘any’ cost, Churchill planned up due response to quell the cancerous fascism. Subsequently, Churchill was conflicted over the formidable human cost his decision would bring upon fellow Brits. Darkest Hour is at pains to showcase how Churchill succeeded over those political obstacles and put up with inner torment to cling to his sound judgment that eventually became the first, big triumphant step taken against Hitler.

Of course, unlike Spielberg’s Lincoln, Darkest Hour doesn’t take a subtle fly-on-the-wall-of-history approach. The movie uses good-old sentimentality and romanticized nostalgia to establish itself as a populist entertainment. In spite of the alleged tear-jerking moments and rabble-rousing speeches, the complexities of the pivotal historical moment remain underdeveloped (the script by Anthony McCarten isn’t exactly hollow yet it lacks profundity). Nevertheless, the film stays compulsively watchable due to Gary Oldman’s rousing performance and Joe Wright’s intriguing aesthetic signatures.

Darkest Hour is the third movie of 2017 whose narrative revolves around the Dunkirk evacuation. Nolan’s Dunkirk was a fantastic spectacle that showcased first-hand experiences of soldiers on the ground whose lives were at stake. Lone Scherfig’s Their Finest viewed the Blitzkrieg-era from civilian point-of-view as group of young film-makers were left in charge to boost people’s morale by zeroing-in on stories of ordinary citizen’s courage during the evacuation of Dunkirk. Darkest Hour places Churchill at the helm to look behind the closed doors, in order to reckon the strenuous, conflicted political climate of the time. And, director Joe Wright has previously visualized the chaos of Dunkirk through the breathtaking five minute single take tracking shot in Atonement (a wonderful adaptation of Ian McEwan’s novel). In fact, Wright and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel’s (Amelie, Inside Llewyn Davis) effective creative choices bestows magnetic imagery into the otherwise talky chamber drama.

Darkest Hour opens with a vertical aerial shot of British Parliament which looks like a dull chamber, fleetingly illuminated by a sun beam. Gradually, the camera moves down to catch up with the screaming members of Parliament. Then the camera horizontally zooms out, crisply revealing the warring factions, seated on either side of the House, who in the earlier vertical aerial shot simply looked like cluster of things pinned over a sprawling map. Now, the reason for the clamor becomes clear: the opposition is calling for resignation of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup). Missing from the scene is Churchill whose notorious reputation however hangs in the air. Then we get an interesting introductory scene of Churchill (Gary Oldman): the future Prime Minister is lying in his robes and drinking booze. He doesn’t come off as the lionized historical figure and not very much an imposing figure. However, when the new secretary Elizabeth Layton (Lily James) fumbles around, Churchill wears upon his haranguing self. The opposition, as Churchill comes to know, won’t accept no other candidate except him. Nevertheless, despite offering Prime Minister job, his own conflicted party members urge for immediate negotiations with Hitler. The narrative moves between 10 Downing Street, Houses of Parliament, stiff meetings with the King (Ben Mendelsohn) at Buckingham Palace, and Churchill’s War Rooms, cramped bomb-proof bunkers, where hundreds of men and women co-ordinate Britain’s war efforts. Amidst the thick fog of war, Churchill has to decide between fighting for ideals and surrender to the all-consuming fascist threat.

Darkest Hour is at its best when capturing Churchill’s dilemmas and his constrained personal relationships. Anthony McCarten also does well in writing Churchill’s clashes with his rivals in the war room. Of course, the script very often includes moments that either plays to the gallery or designed to squeeze out the emotions. Some of those fictionalized crowd-pleasing moments work pretty well, while some remain cringe-worthy. The most heavy-handed scene that I absolutely despised is the prime minister taking the Tube instead of a private car to learn about his subjects’ views on cowering to Nazi menace. The small crowd in the train which includes a pre-teen girl and a black man actively denounces fascism and sees Churchill’s poetry recital with amazement. The crowd’s solidarity and nationalist furor elicits warm tears from Churchill. It’s a blatantly propagandist sequence, designed to elevate or sanitize Churchill’s persona for the contemporary viewers. Instead of bringing out the contradictions that surrounds Churchill, the final strands of the narrative gives into the temptation of reinforcing his mythical image. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t fascinating yet entirely fictionalized scenes which digs beneath the surface. Take the phone conversation between Churchill and Roosevelt, where the American President firmly states his reluctance to involve in war with Germany. Historians suggest that such earnest conversation didn’t happen in spring 1940, yet the Prime Minister’s appeal in this scene was very moving. Another interesting factor in the story was the slowly evolving mutual admiration between King George VI and Churchill.

The personality clashes in Darkest Hour piques our interest more than the behind-the-doors political decisions. The film’s highest points are the tender as well as darkly humorous exchanges between Churchill and his wife Clementine, between Churchill and secretary Layton, or King George. Furthermore, thanks to the excellent actors those verbal stand-offs are brilliantly played out. Lily James’ Layton reminds us of the role Alexandra Maria Lara played in Downfall (chronicles the last days of Hitler and his inner circle). Kristen Scott Thomas despite her minimal appearance on-screen weaves a robust portrait of Churchill’s wife, who now and then pricks at her husband’s inflated ego. Both Oldman and Kristen Scott share excellent on-screen chemistry, diffusing subtler shades to their relationship. More potent are the scenes between George VI and the Prime Minister. Ben Mendelsohn’s is much more nuanced than the Oscar-winning performance of Colin Firth’s George VI (in The King’s Speech). Mendelsohn doesn’t overplay the king’s disability (his stutter), ably divulging his insecurities and feelings of intimidation in facing Churchill. Spearheading all these impressionable acting is Gary Oldman’s impassioned central performance. Oldman doesn’t just hide behind layers of make-up to make a passable attempt at Churchill imitation, but truly gets under the skin of the famous political figure and breathes emotional depth into the scenes which otherwise would appear to be hollow. Arguably, Oldman’s roles can be either categorized as blustering (Leon, True Romance) or subtle (Immortal Beloved, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy). By embodying Churchill, Oldman ably sways between both sides of his acting spectrum, offering flamboyant speeches as well as nuanced mannerisms. Director Joe Wright isn’t particularly subtle with the use of symbolism yet his aesthetic flourishes, as mentioned earlier, are very pleasing to watch.

Darkest Hour (125 minutes) is an entertaining dramatization of the early days of Winston Churchill’s leadership and the idealistic decisions he took in the face of Nazi terror. At times, the narrative paints an over-romanticized and utterly simplistic portrait of Churchill, although the stirring performances provide a sedate movie experience.