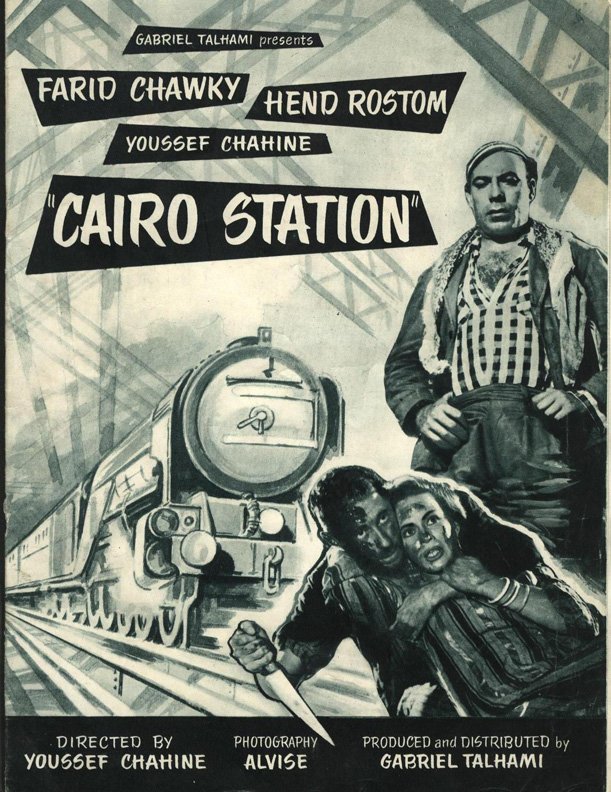

The unbridled energy, immediacy and meticulously visualized set-pieces in Youssef Chahine’s Cairo Station (aka ‘Bab el hadid’, 1958) could serve as the fine introduction point to one of Egypt’s most renowned and controversial film-maker. Mr. Chahine (1926-2008) directed 36 feature films between 1950 and 2007, and Cairo Station (his 11th movie and as some say it is ‘Chahine the auteur’s 1st film’) was acclaimed as his first great artistic breakthrough. Cairo Station stands tall as a crowning achievement in Youssef Chahine’s oeuvre due to the eclectic mixture of tone and styles. It was one part social commentary in the vein of Italian neorealism, one part lighthearted comedy, and one part psychosexual horror. Somehow, those entirely different styles co-exist to create an experience that’s incredibly captivating. However, the film during its release didn’t fare well with critics and audiences. Film researcher Mr. Joel Gordon in his essay (Broken Heart of the City) on the movie writes that the numerous walkouts during the film’s initial screening was due to Chahine’s radical departure from his melodramatic genre conventions (Cairo Station has niggling amount of melodrama). While the late 1950s Egyptian movie-goers were appalled over the distressing resolution and the frank exploration of psychosexual behavior, the foreign critics of the time belittled it for the hybridized film-form (confirming neither to neo-realist standards nor melodrama). The film was of course re-discovered and acclaimed twenty years after its first premiere. Cairo Station went on to achieve international recognition and it was screened at Cannes when Mr. Chahine received life achievement award at Cannes in 1998 [In 1951, Cannes invited Chahine to show his film ‘Nile Boy’].

The 1950s were one of the most turbulent decades in Egyptian history. It was the decade monarchy was overthrown by Gamer Abdel Nasser, who officially became the country’s President in 1956 and served until his death in September 1970. Cairo bustled with life amidst numerous crisis and structural changes (at the same time international crisis sparkled when Mr. Nasser nationalized Suez Canal Company). In this transforming backdrop, directors like Yousseh Chahine were set to transcend the rigid boundaries of national cinema. The little relaxation of the censorial parameters during revolutionary regime was said to have facilitated film-makers to take to the streets and explore societal ills through camera (although Cairo Station was banned after the public demand). The film opens with an excellent montage and voice-over proclaiming ‘Cairo Station as the heart of the capital’. And, the station does remain as microcosm of the city with burgeoning sociopolitical conflicts. The narrative takes place with in a day (may be only 11 hours or so). The voice-over that serves as a prologue perfectly sets up the central character Qinawi (played by Youssef Chahine himself), his defeats and the irrepressible sexual frustration.

The narrator is Madbouli, a genial elderly man who runs a newsstand in the station platform. He takes in poor Qinawi, whose limp is often a source of ridicule. Qinawi now works as newspaper vendor and dwells in a decrepit tin-shed that’s affixed with pictures of scantily clad women. The day the narrative is set begins at 7.30 a.m. with a shot of group of middle-aged men, cloaked in business suits and traditional garb, waiting in line at the ticket counter. One man ogles at a young woman, and the other is standing at the wrong queue to get a ticket. Those little gaze and chaos entwines the realism into setting, which is punctuated with mundanity as well as the extraordinary. Director Chahine rapidly sets up the other two important characters in the film: Hanouma (Hind Rostom), a beautiful free-spirited young woman illegally selling soft drinks in buckets to passengers and often chased by guards; and Abu Serih (Faris Shawqi), an idealistic, strongly built porter desperately trying to form a union, who is also Hanouma’s fiance.

Qinawi is obsessed with plucky Hanouma and at few occasions he obscenely leers at her. He corners her and offers his own marriage proposal. He further shares his dream to live peacefully in a rural village. ‘We will be very kind to our children’ he expresses to Hanouma. The sadness in his eyes when he says those words suggests of toughest childhood Qinawi has experienced. But she is set on course to prepare her trunk and take a train journey in the evening and marry Abu-Serih the next day. Meanwhile, Abu-Serih is intent to join members for his union (he requires at least 50) as the government delegate is visiting the station in that particular day. He gives impassioned speech before the workers, hoping to pry them out from the dominance of corrupted old leader Abu Gamel. Among the other idiosyncratic episodes in the movie, the one which indirectly sets up the narrative course is the infamous news story about the discovery of woman’s torso in a trunk (with heads and limbs missing). Often a figure of derision, Qinawi keeps on receiving emotional and physical bruises. These bruises alongside the repressed sexual frustration distort his grasp on reality and gradually a ‘perfect’ plan forms on his beleaguered mind.

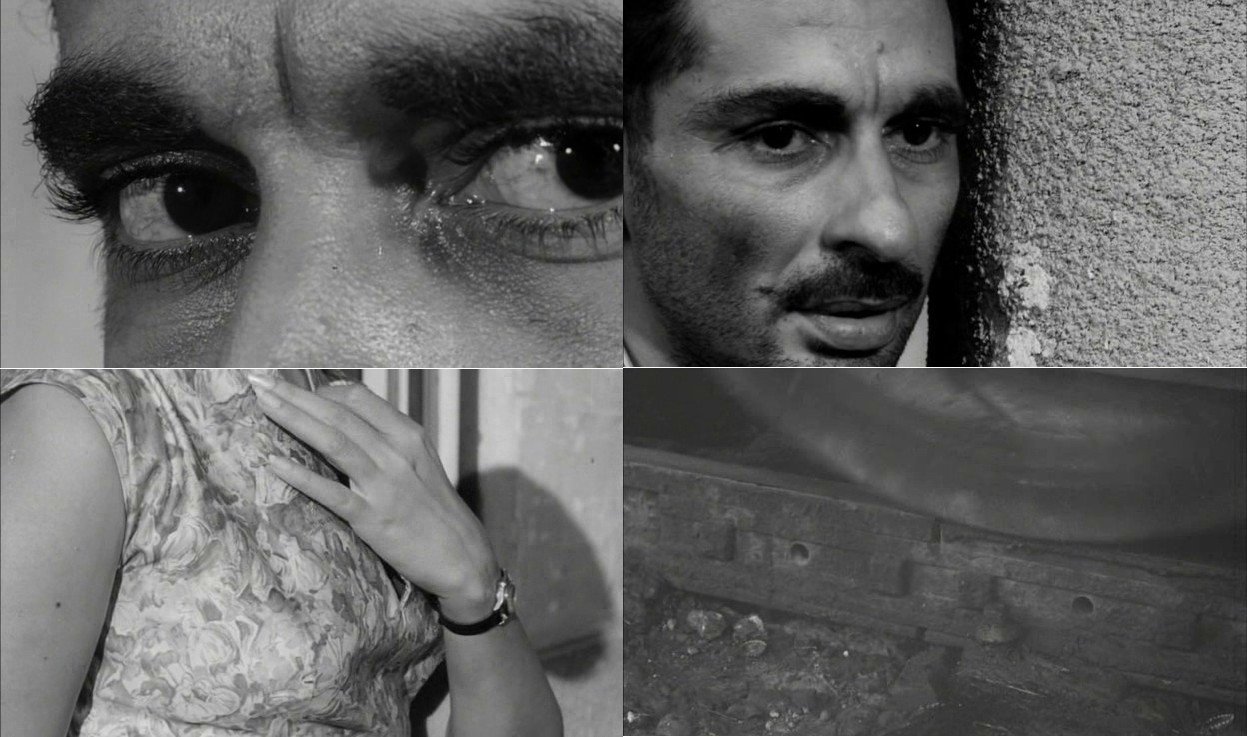

The excellent script by Abdel Hai Adib and Mohammed Abu Youssef succeeds in fleshing out the complex characteristics of Qinawi. Qinawi is without a doubt a pervert and a disturbed individual who frequently anticipates catching a glimpse of cleavage or other curvy parts of women’s body. Although the character is unlikable, he is presented as a human; not as monster seeking its prey. Moreover, Chahine’s impeccable acting bestows Qinawi with a depth which makes him alternately sympathetic and repulsive. Chahine imbues the look of a wounded animal in Qinawi’s eyes, except for the time he devours female bodies through his stares. His perfect facial and body expressions works as the window to look into the mind of a sexually repressed individual. Director Chahine later confided (in an interview) that no other Egyptian actor of the time would have played a physically challenged and emotionally disturbed lead-role like Qinawi.

The groundbreaking direction techniques, however, is the predominant element which elevates the film to masterpiece status. Chahine spellbindingly unites Qinawi’s dark thoughts with the noisy, dilapidated environment. There are Bressonian touches in the way Chahine closely studies the man’s obsession, fear, and excitement with respect to his surroundings (Bresson’s perfect realization of his distinct film-form came a year later in the renowned classic Pickpocket). Michael Powell is another masterful film-maker who comes to mind when Chahine intensely explores Qinawi’s descent into insanity. Furthermore, the director’s approach to escalate tension by playing with light and darkness brings Fritz Lang (“M”, 1931 – an earlier examination of a disturbed individual) and Hitchcockian elements to the surface (obsession and voyeurism are the recurring themes in the works of Lang, Hitchcock and Michael Powell). One of my favorite, neatly aligned shot happens when Qinawi is burdened by the day-time dallies between Abu Serih and Hanouma (in a warehouse). There’s a close-up shot of his face juxtaposed with the shot of railway track, slightly bobbing up and down as string of locomotive wheels move upon it. We not only equate the relation between these two controlled shots, but also understand the course of action he is about to take.

What set apart Chahine’s study of sexually repressed man from other similarly themed films are the odd black as well as light-hearted comic touches. When Qinawi decides violence is the only path left before him, a shot opens before a knife stand with big and small knives hanging upside down (a remainder of the phallic symbol). The seller asks, with no idea about Qinawi’s intention, ‘Can I help you?’ The conversation between young women selling soft drinks and their hard efforts to make a living under the scrutiny of guards leads to boisterous gags. In one such jubilant, stylized scene, Hanouma raucously dances to the tune of a rock n roll group and even winks at the camera (or may be at the conservative audience group). Apart from the fine marriage of styles, Chahine excels at weaving the palette for his neo-realist setting. The Cairo station is framed as a place of motion and emotion with its occupants ranging from peddlers, beggars to police officers and rich, well-clad passengers. Although the mid or low-level shots of Chahine champions and empathetically regards the plight of the poor, he doesn’t tediously villainize the other social classes. The solitude of the beautiful yet distressed damsel which lingers in the film’s final shot painfully echoes alongside the subjugation of Qinawi. The episode involving this unnamed young woman character also serves as the point to depict Qinawi’s compassionate inner psyche. We only study this woman’s story through Qinawi’s eyes, sans the perverted look.

Cairo Station has melodramatic touches here and there, but it doesn’t mar the realism of then relevant social issues. It conveys the broadened perspective of a society, striving to move forward while at the same time deep-rooted in poverty and social ills. It also provides a micro perspective of three individuals who in a way are the collective embodiment of a country, which needs a union of workers and should transcend its rigid sexual boundaries. Perhaps, the movie maintains its classic status because of Chahine’s elegance in neatly pulling the broad and narrow perspectives; the layers pertaining to the study of individual and society never tries to reduce each other’s importance.

Cairo Station (77 minutes) is a riveting character study which distinctly combines stark social realism with genre styles. It stands as a representation of director Youssef Chahine’s — the international face of Egyptian Cinema — eclectic and emotionally-charged storytelling approach.