At a moral level, I don’t think we have any lesson to learn from Europe

- Ousmane Sembene

Senegalese author, screenwriter, and director Ousmane Sembene was one of the first sub-Saharan African film-maker to take his humanist films for viewers around the globe (best known as ‘Father of African Cinema’). Unlike Western movies’ controlled image of Africa, Sembene’s movies cleared itself of the stereotypes & dehumanizing portrayals. Film Critic Jonathan Rosenbaum argues that Semebene’s works gains importance because of the pure African perspective (or authorship), compared to the perspective of a well-meaning European. Ousmane Sembene (born Jan.1, 1923) was the son of a fisherman, who migrated to France (in his early 20s) due to the ravages of war. He worked at the Marseilles docks and joined French communist party and anti-racist movement. In 1960, Senegal declared independence and one of the trips back to home provoked Sembene to communicate with different classes of people through literary means. He established himself as a novelist and a short story writer. Few years later, he enrolled at Moscow film school (also briefly worked in Moscow’s Gorki film studio).

Ousmane Sembene saw cinema as a means to elevate or kindle the society’s political and cultural consciousness. His criticism on the Western colonialism and archaic views of the African society employed deeply artistic methods rather than a didactic approach. The seminal works of Sembene reexamined the colonial history and African traditions from the well-rounded perspective of the African people. Through this process, he tried to rediscover their people’s identity and showcase disparities of post-colonial African societies. In 1963, Sembene made an artful, audacious short film ‘Borom Sarret’ (about a horse-driven cart driver), which is often cited as the first sub-Saharan African film made by a black African. He followed it up with one-hour feature-film Black Girl (aka ‘Le Noire De…’, 1966). Both Borom Sarret and Black Girl were set in the immediate aftermath of Senegal independence. Black Girl explores the struggles of a young Senegalese woman working for a white bourgeois French family. The relationship between the maid and French couple serves as microcosm for the colonized people’s victimization.

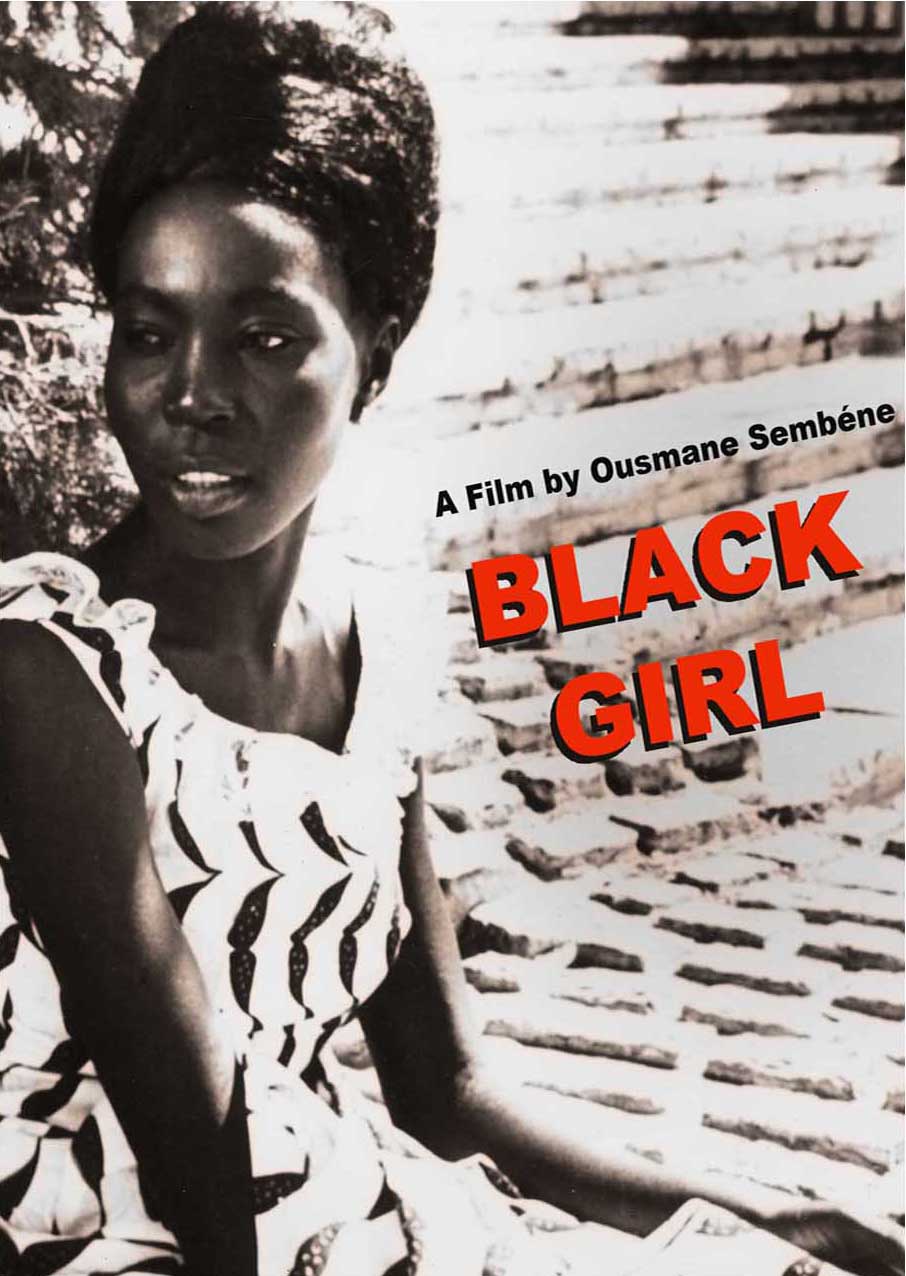

Sembene’s black-and-white debut feature was entirely shot in location in Dakar (capital of Senegal) and Antibes, France. Based on one of Sembene’s own stories of colonialism, Black Girl won France’s prestigious ‘Prix Jean Vigo’. The movie opens with a shot of ocean liner reaching the French coastal town. Diouana (Mbissine Therese Diop) arrives with a single suitcase, cloaked in a beautiful, chic polka-dot dress. The Western attire Diouana hopes would allow her to blend in with the French Riviera community. Her employers are simple addressed as Madame (Anne-Marie Jelinek) and Monsieur (Robert Fontaine). At her room, Diouana wears a pair of white daisy earrings, symbolizing the flowering youth of the girl. Diouana has had fantasies about traveling across France and visiting posh shopping centers. But to her dismay, she is simply given the works of a domestic slave. A brief flashback reveals that in Dakar (Senegal), Diouana worked as a nanny for the same indifferent couple’s three children. Though she was promised the same job in Antibes, the children isn’t present (apparently studying abroad) and Diouana was asked to sweep floors and prepare different spicy cuisine for the rich, prejudiced guests.

Diouana isn’t locked up by her masters, but still her own lack of education and self-worth, escalated by years of poverty and unemployment, leads the girl down the whirlpool of depression. Materials like high-heels and daisy earrings are few things that retain her sense of hope and dream. But the madame repeatedly insists to not wear those things during house work. The madame even shoves a dirty apron to affix Diouana into the paid, domestic slave status. The girl endures all the petty tyranny of her employer with a placid face and expresses herself only through a vividly detailed internal monologue. She is deeply unsettled at the prospect of this life being an alternative to her life in Dakar. Diouana stages little revolts against the madame, but a letter from the mother completely breaks her down The film culminates with a tragedy and also a brilliant final scene, which conveys the film-maker’s righteous fury through a profound symbol of an African (Dogon) mask.

Black Girl went unnoticed after its Cannes screening and Sembene’s style was considered to be too simple amidst the raging French New Wave era. The film also faced many technical shortcomings. The chief among them is the recording of internal monologue (done by French actress). The internal voice is erratic in its tone and fails at times to convey the despondence of Diounana. This is only a minor flaw in a movie, strengthened by rhythmic, non-intrusive direction of Sembene. Although Black Girl has a deceptively simple story, each of its multi-layered moments profoundly studies the effects of neocolonialism. Director Sembene casts a non-judgmental eye towards all of his characters. The employers are not shown as cruel, but only as apathetic individuals, incapable of understand the girl’s decline. Sembene doesn’t shy away from explaining the meaningless nature of Diouana’s dream: like using the wages to buy stylistic dress and send pictures of her to the relatives in order to make them jealous. Through this ultimately shallow dream, Sembene explores the ridiculous expectations and desires, saddled by colonizing nation upon the poor natives. The expectation of happiness through materialistic orientation is pretty much an idea proposed by economically exploiting, consumerist nation-states. Despite independence and decolonization of Senegal (or other colonies around the world), these shallow dreams seems to be deeply rooted and becomes essential for the thriving of class-ridden consumerist societies.

Sembene’s angry tone is plainly visible in certain sequences. He justly criticizes about how the people of so-called ‘Third World countries’ are repeatedly exoticized by the European or Western bourgeois communities. In one scene, a guest kisses Diouana in the cheek, saying “I have never kissed a Negress before!” It depicts how the young girl is seen more as an exotic object (similar to the spicy cuisine or antique artwork) than as a fellow human being. The power of Black Girl lies in the way Sembene combines his ideas (which doesn’t fully turn into a political manifesto) with unique artistic techniques. For example, the manner he uses the ‘wooden mask’ as a recurring visual motif. Diouana offers the antique mask as a gift to her employers when she first works for them in Dakar. The mask is placed alongside other great works of art. Later, Diouana sees the mask in Antibes’ home as it is nailed against the cold, white wall in the living room. No other artworks are seen in the wall near the mask, which seems to mirror the Diouana’s isolation. The mask’s menacing presence could be experienced in the final scene when the meek French employer travels to the impoverished quarters of Dakar to return Diouana’s belongings. A little boy wears the mask (Diouana’s brother) and chases the guilt-ridden monsieur out of their quarters. It’s like chasing away the callous exploiter or colonizer, but the boy’s pursuit with the mask doesn’t pronounce any small victory over the oppressors. A poignant final shot follows where the unmasked, devastated face of the boy looks towards the camera; a shot that questions the aftermath of the personal and collective loss due to wounds of imperialism; one that delivers the same impact of one receiving a fist to the face.

Black Girl (65 minutes) focuses on the realities of post-colonial Africa from a rare, humanist perspective of a Senegalese girl. It reflects the unexpressed emotional despair of people whose voices are persistently quelled in the neo-colonial societies.