Author Janet Frame was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, on 28 August 1924. With a pudgy body and mushy cloud of orange-red curls, Janet Frame right from her childhood found it hard to fit in. She lived with poor working-class parents, three sisters and a brother. The green hills and blue waters gracing the atmosphere of the Frame’s family farm have enough beauty to soothe one’s mind and heart. Yet, the poverty of 1930s and early 1940s had plunged Janet into a tortured childhood. Janet, however, decorated her isolated world by focusing on poetry and short stories. In her adulthood, Janet was misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. For eight long years, she was locked in the soul-sucking spaces of a mental asylum. Thankfully, her creative skills weren’t affected. She took the preordained path to become a full-time writer and went on to gain great literary reputation over the years. Janet was far removed from conventional family life and lived in a unique state of freedom, until her gentle soul departed the earth on January 29, 2004.

In the early 1980s, Janet Frame commenced her writing on three volume autobiography, collectively titled as ‘An Angel at My Table’. The first volume ‘To the Is-land’ was released in 1982 and 28 year old New Zealander Jane Campion after reading the book immediately went to Frame’s flat seeking the rights for a movie adaptation (on December 24, 1982 as quoted in ‘Guardian’ article). Campion read her first Janet Frame novel (Owls do Cry – considered it as one of the best novels to hail from New Zealand) at the age of 14. With a BA in anthropology and BA in painting major, Jane Campion has just entered the film-making universe in the early 1980s. She is yet to make a short film. And, fascinated by Campion’s boldness, Janet asked Campion to wait until the release of the two more volumes. Janet also promised that she would not sell the rights to others. Jane Campion, after directing her first spectacular feature-film Sweetie (1989) decided to get back to the dream project. The movie also titled An Angle at My Table (1990) was initially planned as a mini TV series. But armed with an interesting script from Laura Jones (High Tide, Angela’s Ashes), Campion opted to make a lengthy feature-film (157 minutes). The film stole the heart of movie-lovers when it was first screened at Venice Film Festival and signaled the arrival of a great film-making talent.

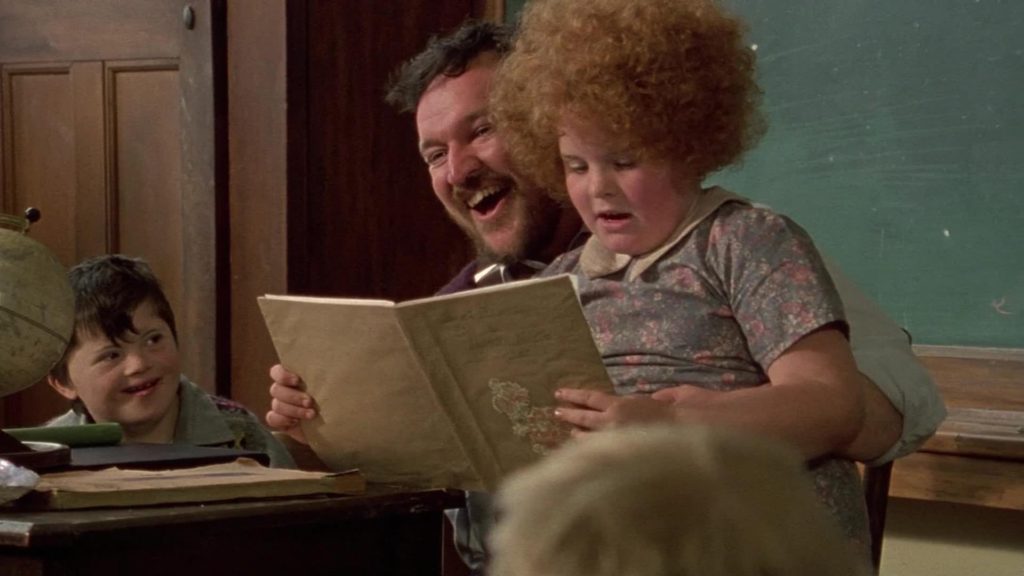

The film was divided into three parts, in tune with the auto-biography’s three volumes. The first one chronicles Janet’s childhood years, followed by distressing teenage years and then the independent years, when she chased after her dream. Few years back, before watching the film for the first time, I was skeptical about it. A biopic with a 150 plus running time didn’t interest me much. But, when little, plump Janet with a brightly colored tousled hair walks into the frame, set against striking post-card beauty landscape, I was instantly engrossed. The next two-and-half hours quickly passed away, instilling a powerful, emotionally overwhelming movie experience. The biggest strength of An Angel at My Table is the way director Campion adheres to a unique visual style which feels so organic and natural that you don’t feel like observing the life of some relatively unknown author (I didn’t come across any of Janet’s books before watching the biopic) from remote corner of New Zealand. The yearning, the delight, and the misery faced by Janet Frame directly speak to our hearts, unlike many traditional biopics. The film also happens to have one of my most favorite female performances. Kerry Fox’s portrayal of Janet Frame is one of the primary reasons for me to often revisiting this magnificent work.

Most of the biopics are carried away by the idea of reiterating the important facts of a famous personality’s life that the entire film becomes a visual metonym of a Wikipedia page. It doesn’t happen with Jane Campion’s film. Screenwriter Laura Jones’ script has a traditional structure and is full of intriguing vignettes. Yet, it stays away from biopic conventions. Director Campion primarily realizes the rich inner life of Janet Frame with perfect casting of actors. The minimal self-esteem, isolation, love, and yearning are subtly affixed to the character. The little Janet’s domestic life varies between bitter and bittersweet. We witness her large family (dad is a railway worker) scraping through the depression era. Janet looks up to her outspoken and very beautiful elder sister Mrytle. Nicknamed ‘Fuzzy’ by her schoolmates, Janet was never adored like her elder sister. Her small attempts to make the schoolmates look up to her only adds up to the misery. But, Janet also understands that she is different and special because of the ability to write spectacular poems. The child was duly encouraged by the dad who gifts her first notebook.

Nevertheless, tragedy always has an overwhelming presence in the Frame family farm. Despite the exuberant beauty of the landscape, the economical troubles of the era push the family to live in a rusted old-house at the center of nowhere. Janet’s young brother Bruddie suffers from epileptic seizures. Delightful teenager Myrtle dies in a drowning accident. This tragic incident creates a big emotional scar on the family, setting in the alienation (some years later, Janet’s another sister also died in a drowning accident). The shy, teenage Janet (Karen Fergusson) is also burdened with sexual loneliness as she is wary about talking with boys. She boards a room in strict aunt’s house. Although she dreams of becoming a full-time writer, the solitary life only puts her on the path of becoming a teacher. A little anxious moment makes Janet to throw away her teaching career to only work in the kitchens of the college. All this time, Janet becomes a more introverted person, finding solace only in writing from the cramped resident space.

The feelings of uncertainty and the failure of others to understand Janet’s personality eventually bundles her up to a mental asylum. In the old, apathetic mental healthcare treatment system (the 1940s &50s), Janet’s emotional condition worsens. Wrongly diagnosed with schizophrenia, she is subjected to hundreds of electroshock treatments (‘each one equal in fear to an execution’ recalls Janet). She very nearly escaped from being lobotomized. It was so painful to look at Janet’s expression of fear when the doctor says she is not going to be lobotomized and that her book has won a prize. After being in the hellish environment for eight years (at Sea-cliff Lunatic Asylum), Janet faced the prospects of a better future as her books gained some reputation. A generous admirer of Janet’s works arranges for a literary grant to travel around Europe. The intention was to experience a bit of cultural shock and to broaden her perspective. The trip proves to be fruitful and Janet even has a romantic fling with an American teacher (in Spain). Eventually, after her father’s death, Janet was drawn to homeland. She now returns to New Zeland as an energetic, confident and free woman. From then on, Janet’s splendid literary voice resonated within and outside the island nation.

Director Jane Campion has the unparalleled knack for capturing human emotions. She simultaneously creates this fragile world of little Janet and keeps our emotions attuned to it. Take the scene, when the little girl’s plan to make the classmates adore her totally flops or the tragicomic scene when child Janet says the word ‘fucked’ at dinner table, we are absorbed by the character’s emotions. Campion tightens the frames with close-ups when little Janet experiences the bitter things. Finally, when the child realizes that she is not only different from others, but also has a unique gift of writing, Campion’s tight frame now provides a sort of emotional catharsis. This ability to closely observe Janet’s emotional conflicts, loneliness and the ultimate relief provides a window to the real Janet’s soul. The unbelievable finesse in each sequence delivers a very pure cinematic experience. There’s none of the additional visual flavors; something to distract our attention or to strongly make a point. As expected, Stuart Dyburgh’s framing of New Zealand is a wonder to behold. The true talent of Dyburgh-Campion, however, is more visible in the mental asylum sequence as they go for bluish tint and tighter frames to evoke the unsettling mood. The brief phase of cruelty experienced by Janet passes off the agony and strangely subverts from the visual cliches of depicting mental asylum.

Writer Laura Jones and Campion were clever enough to understand what matters in the biopic. They inject the facts from Janet’s life, but the primary task was to impeccably present a strong female figure, who wasn’t brought down by numerous tragedies in life. In the interview to Guardian, Campion recalls how she felt when reading Janet’s Owls do cry at the age of 14: “she affirmed it in me, and in countless other sensitive teenage girls that we had been given a voice: powerful and poetic”. The same could be said about Campion’s visualization of Janet Frame’s life. She addresses the desires of female figures, which isn’t often addressed in the movie framework. While there have been countless dramas about introverted, talented male artists, we don’t find a lot of cinematic works about similarly great female artists. But, of course Campion’s works differs from what you could refer as ‘rigidly feministic’ (what they label as ‘cinema only for women’). It is captivating to see the female gaze of a male body or the moment when the girl realizes her sexual desires or comes to terms with her own body’s limitations. Yet, the overall mood is achingly humanistic. The female subjectivity or female experience works in tandem to impart universally recognizable human emotions. Every introvert (male & female) could feel Janet’s yearning to be at the center of a larger group and the accompanying doubts and shyness that stops us from making that yearning come true. For highly talented introverts, the inability to mix in a group in fact kindles their artistic persona.

Kerry Fox as Janet Frame is absolutely phenomenal. There’s couple of splendid scenes of her that would always stand out in my memory: When Janet is sensually touched by a man; When Janet cleans her old farmhouse. In the former scene, Janet’s body experiences something new and special, yet at the same time her mind says the opposite: to withdraw which she eventually does. Kerry Fox astoundingly captures Janet’s emotional conflict in this scene. In the later scene, Janet finds her dad’s old boot. She slips her feet inside, trying to imitate her father’s mannerisms. This is another beautifully enacted intimate moment that our emotions are perfectly in tune with the on-screen character’s.

An Angel at My Table (157 minutes) must be watched to witness Jane Campion and Kerry Fox’s remarkable collaboration in order to weave humanistic portrait of a woman with an unbreakable spirit. As far as the biopic goes, this is one of the best ever made.