Oppenheimer Defining Films Of Our Era? By the end of the decade following World War II, America’s nuclear weapons stockpile had leaped from some 300 warheads to nearly 18,000 nuclear weapons. Over the next five decades, the US produced over 70,000 nuclear weapons, spending a staggering $5.5 trillion on their nuclear weapons programs. Later, the decision to go ahead with making the Hydrogen-bomb proved to be a turning point in the Cold War’s spiraling arms race.

Christopher Nolan has said in multiple recent interviews how he thinks J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man history calls ‘the father of the atomic bomb,’ remains “the most important person who ever lived.” The filmmaker has also cited how the contemporary moral quandaries posed by the advancements in artificial intelligence mirror those faced by Robert Oppenheimer himself. In one such interview, present-day theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli joined Nolan to talk about how the story of Oppenheimer fits into the 21st century.

Every movie should be free of the burden on the audience of having a prerequisite to reading about its subject going in. But things become different when dealing with a figure whose life was as tragically grandiose as Oppenheimer’s. Based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer-prize-winning book, “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” Nolan wrote the film’s first-person screenplay during the COVID-19 pandemic. But his 3-hour long biographical drama about the titular character demands no less subtext about the man going in as it requires a careful examination of our cultural point.

Needless to say, the film is densely packed, juggling different timelines and mostly playing out, to paraphrase one character, in “shabby little rooms far from the limelight.” Nolan’s most noteworthy achievement as one of the most important contemporary filmmakers is how he’s repeatedly brought science into the public consciousness. In “Oppenheimer,” the story unfurls along two oscillating lines – one titled ‘Fission’ which plays out in vivid color, and the other titled ‘Fusion’ in monochrome. Unlike the book it’s based upon, the film plays out non-linearly, cutting between beats and revelations about the controversial physicist’s life with a riveting sense of urgency, reminiscent of the 70s paranoid thrillers as well as Oliver Stone’s incredible “JFK.”

Like the physicist’s desire to bring his two muses in physics and the canyons of New Mexico together, Nolan deftly recreates most exteriors of the movie at Ghost Ranch and Santa Fe. Moreover, casting famous actors as supporting characters – most of whom appear as mythical beings for their contribution to science and history – make an impact in that you realize the gravitas of their presence on screen. After all, the filmmaker is best known for using visual cues that orient viewers into his grand narratives so they don’t feel lost.

But unlike conventional biopics, “Oppenheimer” strictly serves as a portal into the life of a man who bore the weight of his intellect and the guilt of his creation, not a chronological portrait of his life. In that regard, it aligns with biopics such as “Andrei Rublev” that steer away from the basic cause-and-effect structure while turning inward. Thus, Nolan imposes the cultural undercurrents and sensibilities of the McCarthy-era on the life of one person who found himself right at the center of its combustible fallout. The notable absence of dates or location-providing subtitles further helps the movie function on a different level in terms of its understanding of time and history.

In doing so, the film uses Oppenheimer as a static and ultimately tragic beacon to examine the hopeless state the nuclear age has left us with. That’s also what makes the film the most in control Nolan has been of his craft; by tethering the film to a sense of shared history, the director avoids the pitfalls of loudly submitting his audience to half-baked and intangible leaps of faith in the narrative. In fact, much like Wes Anderson’s recent film, “Asteroid City” – another deeply ruminating film that examined the paranoia of living in a nuclear age – “Oppenheimer” too sees a pre-eminent auteur fully committed to his filmmaking style.

Nolan’s movies are best known for compacting and conveying hefty narrative information through visual demonstrations. The scene from “Interstellar,” where a wormhole is explained by showing a folded piece of paper and then poking a hole in it with a pencil, comes to mind. While the filmmaker has been criticized for his frequently expository dialogue, “Oppenheimer” adroitly turns every technical decision into a well-thought-out storytelling choice. The information laid out then doesn’t become an act of lazy writing but a tool to better service the subjective view and sheer obsession with which the titular character approaches his project.

It’s also startling to see how committed the screenplay remains to the actual transcripts, laced into the film with Jennifer Lame’s feverish editing. Despite being the longest entry in Nolan’s filmography, it might just be one of the best-paced movies of the year. It indicates the most confident Nolan has been of not losing his audience through his almost-unfeasible cross-editing. Because of that, even the parts that fail to be factually accurate feel historically immersive.

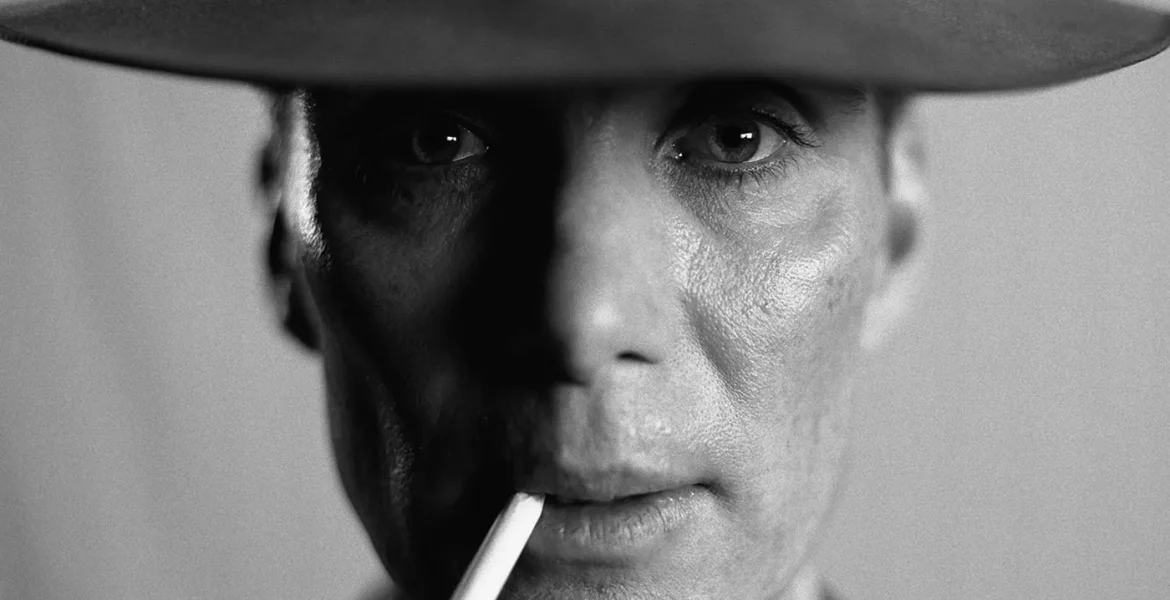

With “Oppenheimer,” Nolan has singularly given us the quintessential antithetical answer to all modern-day blockbusters. By shooting the film on massive IMAX 70mm, the grandest moments and takeaways remain of the microscopic glances and stare that characters pass through shabby rooms. By entirely avoiding the use of CGI, the most visceral moments remain the ones of prodigious stillness, channeling all the scope of the story through their intimacy. The movie tops emotionally and physically with its 10-minute Trinity test sequence but works as a whole even better because it acknowledges the same; it’s the third act of the film that creates a sense of tangible urgency not through visceral or physical action but by showing the political fallout of the decisions made in the first half.

“You’re the great salesman of science,” a character tells Oppie at one point in the film. During another instance, a colleague advises him not to bring his politics to the class. There’s an implication of how Oppenheimer was recruited to oversee the Manhattan Project not despite his Communist connection but because of it. Although the film brushes past his early years of life before he eventually got into Berkeley, the temporal shift into the man’s psyche provides us with the kind of indelible impact his extramarital affair and communist learnings had on his conditioning. But Nolan chooses to crack those dormant doors of guilt open only after the man is confronted with the terrible revelation of his power. The very power that he feared the Americans would let loose if they failed to retain any “moral advantage” after using the atomic bomb.

In one of the film’s most crucial scenes, Oppenheimer and Edward Teller discuss the possible ramifications their creation could entail as they watch the same being carried away to a government facility. As the two men with conflicting moral ideals stand covering each side of the frame, Oppenheimer suggests that just because they’ve built it “doesn’t mean we get to decide how it’s used.” He was right. As we watch the immediate sidelining of the man from the American authorities, granted that his job was done, the voices in Oppenheimer’s troubled psyche begin to supersede his outspoken arrogance.

In one of the best scenes, we watch him speak to his cheering colleagues and subordinates on stage. Oppie knows he has to congratulate them and stay upbeat as a leader. Stammering out a fatuous remark about how the Japanese surely “didn’t like it,” he instantly realizes its callousness as we watch an extra dimension fold upon him.

It’s the only time we really see the recurring motif of stamping feet on screen, played out in a moment of glory and triumph, but one that continues to pierce the film’s soundscape along with the plaguing state of its subject’s psyche. “Oppenheimer” remains a story about dealing with the consequences of your achievements. As the catastrophic potential of the physicist’s work becomes clear, the film spends its second half clawing back onto the man’s individualism, a man burdened by his skills and greatness. After all, that’s what makes it a Greek tragedy.

In a 1955 interview, Oppenheimer was asked whether scientists had been alienated from the government. The repercussions of the same question underline Nolan’s film. After almost 70 years of the physicist’s hounding by the McCarthyites for his communist connections, the film punctures through nauseous air the uncrossable moral chasm between the establishment and the scientific temperament that he has left us with today. The choice of never directly showing the atomic bombings further reinstates the filmmaker’s intention of not making the film about the blast but rather about its fallout.

The double helix storytelling also allows Nolan to expand upon the character dynamics and interplay; simultaneously placing supporting characters adjacent to Oppenheimer, the movie creates visual dichotomies through its two narratives and distinct thematic perspectives. Lewis Strauss and Oppenheimer’s obsession over professional matters soon overlap into an uncontainable personal rivalry until it gets buried under their fragile egos. Just like the opposing nature behind the two scientific processes, the two perspectives also echo the crippling faith of the scientific establishment as a result of its political exploitation.

There’s been a steady rise in metamodern movies for some years now. An increasing number of stories now oscillate between aspects of both modernism and postmodernism in pursuit of navigating truth and reality in an increasingly anxious world. The humongous success of last year’s “Everything Everywhere All At Once” will probably compound the pursuit of such narratives. During such a time, “Oppenheimer” actively responds and interacts with both notions of postmodernism and modernism while preserving the complex interiority of its central enigma. The first half shows the promising aspirations the rise of modernity and American individualism had brought. However, in the second half, the movie criticizes the modernist wave by depicting the terror the McCarthy era had dawned upon the country.

In the metamodern era, as AI continues to develop rapidly, Oppenheimer’s ethical qualms about forgoing the scientific process in favor of national safety looms higher than ever as experts warn of the weaponization of the same. At 90 seconds to midnight, the ‘Doomsday Clock’ now sits the closest it has ever been to midnight. Christopher Nolan’s resounding new film is here as the creeping anxieties brought upon by the climate change catastrophe, political polarization, and the ever-increasing threat of nuclear annihilation loom above us.

In 2023, the story of ‘the father of the atomic bomb’ remains essential as it symbolizes those who voice such disquiet. While his overall motivations and internal turmoil shall remain only areas of academic interest, what remains primary is for every generation to reaffirm the importance of having a moral dilemma. Oppenheimer’s defeat marked the death of American liberalism, as the politics of the time crushed the physicist’s long tenure while changing the context of his New Mexico landscape. The man spent his late years as a social outcast.

The justification for postmodernist theory had become reinforced with President Dwight Eisenhower’s farewell address in 1961 – the famous speech in which he had warned against establishing a ‘military-industrial complex.’ While making the atomic bomb, Oppenheimer kept referring to the kind of international cooperation President Franklin D. Roosevelt had always imagined. But as he soon learned, the good we humans do may never make up for the destruction wrought upon us by our good intentions.