Ruby Sparks: The Deconstruction of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl Persona.

Perception is a fluctuating currency that has the capacity to blind, distort, and disorient our views of the world. Elements like projection, bias, and romanticism are often culpable for such a dissonance. How this translates into a film is through the application of artistic liberties and exaggeration. This brings us to the manic pixie dream girl archetype, the epitome of these factors wielded for the sole purpose of serving the (male) protagonist.

In a lot of ways, the manic pixie dream girl is an extension of the ‘Stepford wife’ and a predecessor to the ‘cool girl’ persona.

To avoid confusion, a definition is in order.

Making the first appearance in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the manic pixie dream girl is the human manifestation of awe and bewilderment. Taking ‘carpe diem’ to a perverted level, this type of character finds whimsy in the most mundane everyday activities.

Having a hard time spotting one? Here’s a tip.

Her preferred venue of entry will likely include windows. She probably doesn’t believe in cars and favors something more magical like roller-skates or a unicycle. She often speaks in proverbs that sound profound but mean absolutely nothing.

Her full name most likely has a noun in it, but most importantly, she is an object to behold and not an autonomous subject.

Now here’s a movie that ruthlessly negates this persona and gives it the Scarlet Letter treatment, Ruby Sparks (a.k.a. the hipster version of Weird Science).

So what’s the story?

Upon his therapist’s request, author of one hit novel, Calvin Weir-Fields exorcises his inferiority complex by writing about his dream girl. Everything he types somehow comes true thus materializing his work of fiction, “Ruby Sparks”. As soon as things get “too real” and his Frankenstein’s monster develops an identity, Calvin edits (and re-edits) the parts of her that he doesn’t like.

At face value, this seems like a retread of Stepford Wives (or any other iteration of the Pygmalion myth- see My Fair Lady), but up close, it’s an indictment of this breed of character.

Given the significance of character introductions when it comes to framing and positioning, let’s look at how the movie presents Ruby and Calvin respectfully.

In the opening shot, we see the silhouette of a woman facing a man. She says to him “There you are. I’ve been looking for you” and then goes on to inquire about her missing shoe (a parallel to Cinderella?) In a way, that perfectly sets the tone for the future dynamic of their relationship. She’s out of focus and underdeveloped while he’s the center of the frame.

This relationship (and movie consecutively) is all about him; his neuroses, his feelings of inadequacy, his abandonment issues, and most importantly his willingness to overcome these issues.

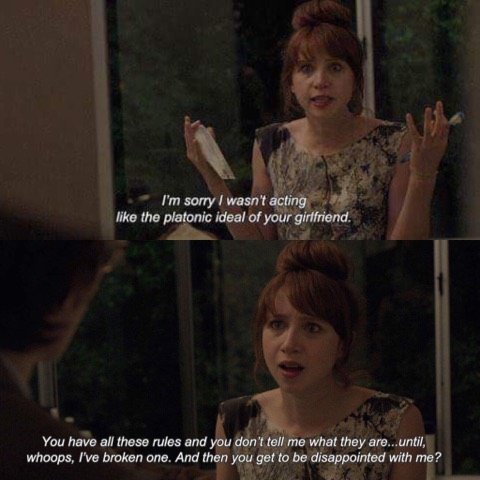

Ruby is just the GIRLFRIEND. Any iota of individuality is prematurely weeded out to fit his ideal of a partner. Thus, she’s confined to being a support system with no arc of her own.

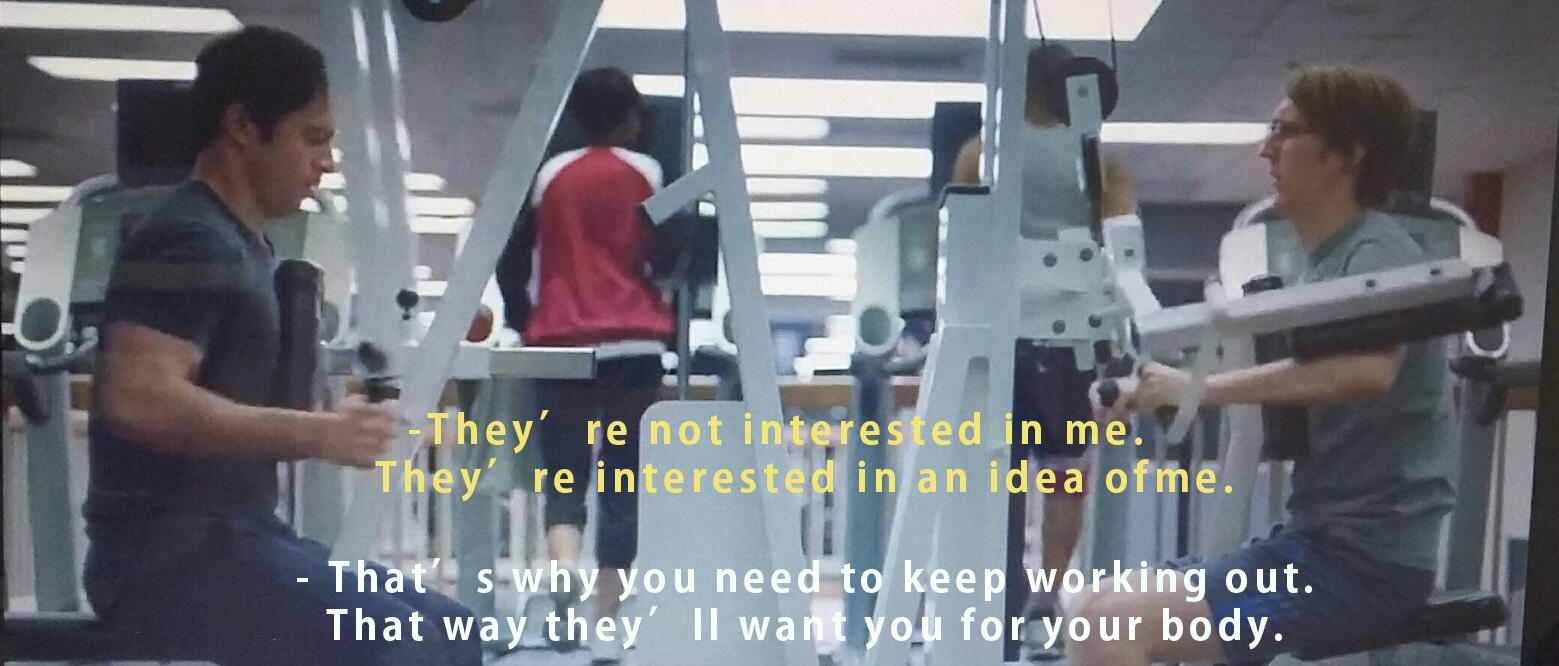

This is a classic case of projection. He treats HER the way the public treats HIM only seeing what they want to see and dismissing everything else. The only person who doesn’t adhere to such behavior is his brother Harry, an uninterrupted supply of reality checks whose main job is to dismantle the bullshit. He’s constantly setting his brother straight and un-muddying his rose-stained glasses. Sometimes seriously like when he says “you’re not writing a person, you’re writing a woman”.

And sometimes playfully so.

Now, Harry’s character is a bit problematic in that he sees Ruby as a science project and treats her as such. While he has an indisputable love for his wife Suzy, he seems pretty seduced by the idea of switching off some of her more ‘difficult’ qualities. As a result, he instructs his brother to take advantage of the situation and change Ruby for “men everywhere”.

This is actually a recurrent theme in movies that feature the manic pixie dream girl. She is a catalyst to the plot, something for the hero to chase.

With that said, Ruby Sparks is basically an intervention for all romantic comedies who romanticize this type of relationship or a stern PSA on why such thinking is inherently toxic.

The question remains, does this movie succeed in giving this archetype a much needed time out? Yes and No.

While it’s not the definitive nail in the coffin, it’s definitely a step in the right direction. As an indirect result, a slew of movies followed suit with the agenda of purging the entertainment industry of the pesky nuisance that is the manic pixie dream girl.

Her is the heavyweight that made the most waves in this endeavor. The film adheres to the clichés only to nullify them through a gradual tour of ‘everything wrong’ with this type of character.

Other less impressive efforts include John Green’s Paper Towns where this trope is courteously ridiculed and rejected.

And with that, a new surge of self-awareness blossoms from the ashes of past mistakes, paving the way for well-rounded characters in competent narratives.

So does this mean that Ruby Sparks is the best parody ever? Well, not really. While it is an adequate entry, it’s not witty enough to merit such a title, but definitely worth at least one viewing. Think of it as a gateway film to the smarter stuff.

This movie is rated G for Guess having free will isn’t really whimsical?