“This list is an attempt to highlight some of the best silent films from the Japanese film industry.”

The silent-era cinema was truly one of the most creative eras in cinema; its commitment to narrate stories, convey ideas, and establish a whole range of visual vocabulary (despite the technological limitations) is a marvel. However, silent cinema is often regarded with condescension; as simply a primitive form of film-making. Such misconceptions could be eradicated after just experiencing a handful of silent-era masterpieces. And it is important for movie-lovers to look beyond the non-stop mediocrities the streaming platforms offer and embrace the unique artistry of silent cinema.

This list is an attempt to highlight some of the best silent cinemas in the Japanese film industry. It’s clearly not a comprehensive list since many films from the era are lost or not widely available (or existing beyond my limited knowledge). It’s rather a simple effort to share my love for early Japanese cinema.

1. Souls on the Road (1921) | Director: Minoru Murata

As I mentioned, early Japanese silent films were known for their excessive benshi narration and simplistic imagery. That’s said to be changed with this landmark Japanese silent cinema, Souls on the Road (Rojo no reikion). Its director Minoru Murata was celebrated as one of those who modernized early Japanese silent cinema. Sadly most of his works are lost and he died at the age of 43 in 1937. Souls on the Road, one of the few surviving films of Murata, was made with an intent to cast away its highly theatrical kabuki influences.

Souls on the Road has four intertwining storylines. It primarily narrates the fate of a penniless son returning home with his family, and the suffering of two escaped yet kind convicts. Based on Maxim Gorky’s Lower Depths and a German novel by Wilhelm August Schmidtbonn, it’s a tale of Christian kindness, set in the harsh winter landscape. Director Murata erratically crosscuts between each story-lines that might initially exacerbate our confusion about the characters. That might be also because this is a patched-up cut and not the full version.

Murata was probably inspired by D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) whose cross-cutting technique covered events happening across four different historical periods. But despite the messy cuts in ‘Souls’ there’s lot to admire: from the storytelling devices (including flashbacks and dissolves) to location shooting and relatively naturalistic performances.

Similar to Japanese Silent Films: The Phantom Carriage [1921] Review – A Startlingly Inventive Morality Play of the Silent Film Era

2. Orochi (1925) | Director: Buntara Futagara

Buntara Futagara’s Orochi (‘Serpent’) is one of the earliest samurai action melodramas. It narrates the timeless tale of a short-tempered yet righteous man, crushed by a prejudiced, class-ridden society. Set in 18th century Japan, the central character Heizaburo is played by Tsumasburo Bando, who became an iconic star of the Japanese silent cinema. Heizaburo is a trustworthy and noble samurai, but he is repeatedly misunderstood by the narrow-minded society. Ostracized by the world, he becomes the bad guy he is said to be.

Like most of the silent films of the era, Orochi is available with Benshi performance, i.e., a performer theatrically provides voices and commentary. Though Benshi tradition was very much an integral part of Japan’s silent era, Orochi is more powerful when viewed without audio commentary. Particularly to appreciate Futagara’s mesmerizing action set-pieces and the production design. Furthermore, Bando as the anti-hero offers a stirring, heartfelt performance.

Related to Japanese Silent Films: The Tale of Zatoichi [1962] Review – The Magnificent First Chapter Featuring the Illustrious Fictional Swordsman

3. A Page of Madness (1926) | Director: Teinosuke Kinugasa

Teinosuke Kinugasa was one of the most important Japanese silent film-makers, whose independent works embrace the European film movements of the 1920s and Soviet formalism (including the montage theory). Mr. Kinugasa was often credited as the foremost Japanese filmmaker to have perceived cinema as a distinct art form. Several critics also championed his works for having crossed cultural boundaries and reached an international audience. Although Kinugasa entered the film industry in the early 1920s, it was the silent avant-garde horror, A Page of Madness (‘Kurutta ippegi’, 1926) that cemented his reputation as a seminal artist.

Set inside an insane asylum, the film revolves around a man (a retired sailor) who takes the janitorial job in the place to be with his insane wife. The details of the plot, however, aren’t easily discernible due to the fact that there are no inter-titles. But A Page of Madness is highly fascinating from a technical viewpoint alone. From its impressive range of cinematography tricks to astoundingly invoking the world of the mentally ill (full of eye-popping psychedelic/surreal sequences), the film is hailed for the audacity of its creator’s vision.

Watch the A Page of Madness Full Movie Here

4. Crossroads (1928) | Director: Teinosuke Kinugasa

The self-financed ‘A Page of Madness’ pushed director Teinosuke Kinugasa into a despondent financial situation. In the two years gap, before embarking on his next artistic, independent project, Crossroads (‘Jujiro’, 1928), Kinugasa was part of many commercial productions. Jujiro is a drama set during the Edo Period at Tokyo’s pleasure quarters. It focuses on the unrequited love of a young man (Rikiya) who is publicly humiliated and temporarily blinded by an old rival.Once again the fantastic visual sensibility of Kinugasa enlivens this story of vengeance and love. The mood-setting atmospheric lighting (influenced by German Expressionism) astutely helps to bring out the gloomy mental state of the characters.

Also similar to Japanese Silent Films – Watch Crossroads Full Movie Here

5. Walk Cheerfully (1930) | Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Days of Youth (1929) is the earliest surviving film among Ozu’s filmography. The filmmaker is said to have made five feature-length films before that (all apparently lost). However, I couldn’t yet stumble upon a decent print of Days of Youth. The next extant silent film of Ozu was Walk Cheerfully (1930) which is a very stylized crime melodrama. Critics note that Ozu was inspired by Pre-code Hollywood dramas, particularly the mid and late 1920s works of Josef von Sternberg.

The story is written by another great early Japanese filmmaker Hiroshi Shimizu. Walk Cheerfully tells the story of a hoodlum and pickpocket Kenji aka Ken the Knife (Minoru Takata) who falls in love with a hard-working office worker, Yasue (Hiroko Kawasaki). Kenji tries to go straight. But a complex, atypical scheme is set in motion.

Gangsters, sultry molls, and guns aren’t the things we would expect to be part of Ozu’s films. But Walk Cheerfully along with The Dragnet Girl (1933) showcases Ozu’s fondness for early American genre cinema. At the same time, Ozu brings an understated quality to the drama. Maybe it’s too plot-centric to accommodate the ‘mono no aware’ we witness in his later films.

Also Read: 5 Essential Takeshi Kitano Movies

6. What Made Her Do It? (1930) | Director: Shigeyoshi Suzuki

Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s ‘What Made Her Do It?’ was thought to be lost for a long time until an incomplete copy was thankfully found in the 90s in Russian archives. Though by the time this film was made, Japan was heavily leaning towards militaristic, right-wing ideology, there were quite a few proletarian political cinemas. It was one of the reasons why ‘What Made Her Do It’ was exported to socialist Russia. The restored print contains additional intertitles explaining the missing portions.

Based on a popular Japanese play, the film follows the tragic spiraling down of its innocent heroine Sumiko (a marvelous and intense Keiko Takatsu). The young girl’s father sends her to live with an uncle in a distant village. The impoverished uncle’s family naturally views Sumiko as a burden. She is soon sold to a circus. Fate takes Sumiko to different places, but the only constant in her life is the cruelty she endures everywhere.

‘What Made Her Do It?’ is a near-masterpiece with perhaps an unforgettable ending in silent film history (though a lot of it is filled with explanatory intertitles). The impressive array of visual techniques employed here only makes us sad over its lost bits. Nevertheless, this is an important tale about female suffering in a cruel world.

7. Tokyo Chorus (1931) | Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Tokyo Chorus (‘Tokyo no korasu’) was Ozu’s 22nd film which is often extolled as a bittersweet family drama on the struggles of a Tokyo-based family. The film’s protagonist Shiji Okajima (Tokihiko Okada), in the opening sequence, is shown as a foolhardy high-school student, giving a tough time to his teacher. Post-graduation, Okajima works in an insurance firm and takes up the duties of a caring family man (a wife and three children).

The recklessness he expressed in school days is now replaced by a sense of idealism, which actually costs him his job. Okajima complete deflation of his ego and education about modern salary-man life occurs when he later meets the same teacher.Tokyo Chorus was one of Ozu’s early films where you could experience his unobtrusive directorial presence and other trademarks (like static camera and grounded shots, etc). The sappy comedy tone (for eg, Okajima confrontation with the hard-headed boss) is although an imitation of Hollywood silent comedies of the era, Ozu expresses serious social themes and familial tensions in his own unique way.

Similar to Japanese Silent Films – 10 MUST-SEE JAPANESE HORROR FILMS

8. I Was Born, But… (1932) | Director: Yasujiro Ozu

In this family drama masterpiece, you could perceive Ozu freeing himself from the influence of Hollywood silent filmmakers (Ernst Lubitsch, Harold Lloyd, etc) and experimenting with a unique mise-en-scene, which later became his film-making signature. I Was Born, But… (‘Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo’) unfurls from the perspective of two little brothers — Keiji (Tomio Aoki) and Ryoichi (Hideo Sugawara) – who has freshly moved with their mom and dad to the suburbs.

Their father (Tatsuo Saito) is a salary-man who is happy to have been offered the managerial position and live in the same neighborhood as his boss. But the boys’ feeling of pride about their father is breached when they understand the reality of their family’s social standing. This is a charming little film with a remarkable visual pattern that mostly sees the social hierarchy from the children’s viewpoint.

9. Passing Fancy (1933) | Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Although the father-son relationship takes the center stage in this silent Ozu film, the father isn’t the disciplinarian like in Ozu’s later films. The freewheeling single dad named Kihachi is played by Ozu regular Takeshi Sakamato, who works at the brewery to give his boy (Tomio Aoki) a decent education. The illiterate father, however, has a weakness for the sake and fancies a destitute yet beautiful girl named Harue. And soon a love triangle develops since Harue likes Jiro, co-worker, and friend of Kihachi.

As usual, one can’t ignore the subtlety with which Ozu directs this simple story about the working poor. The director’s unique visual sensibility creates a portrait of a poor working-class neighborhood and depicts their economic woes in a mix of a comedic and somber tone.

Related to Japanese Silent Films – Watch Passing Fancy Full Movie Here

10. Apart From You (1933) | Director: Mikio Naruse

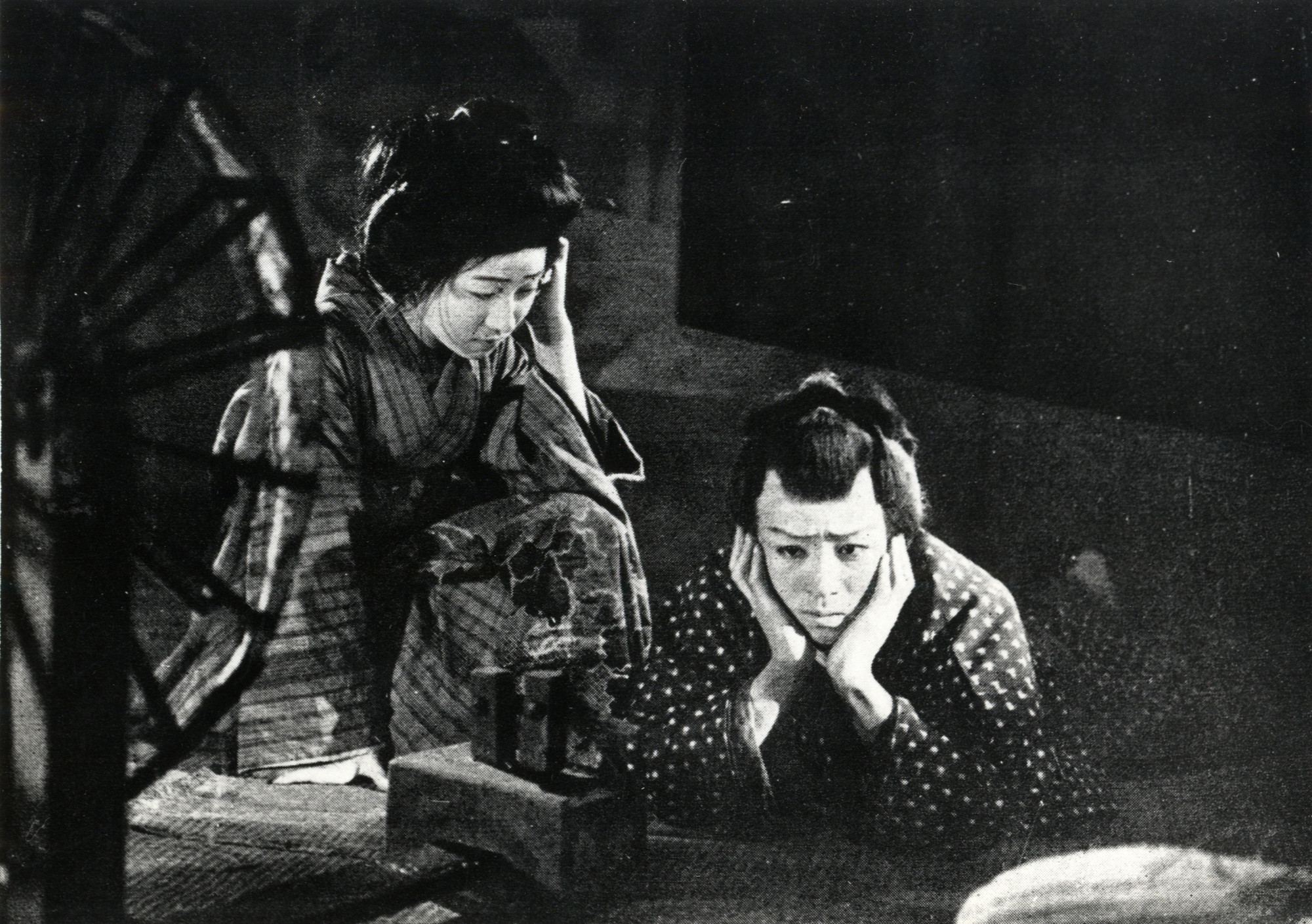

Mikio Naruse’s films often focused on the misfortunes of working-class women, particularly geishas who work at low-end bars, succumbing to the whims of men. Apart from You (‘Kimi to wakarete’, 1933), cited as a critical breakthrough for Naruse, contains all the familiar themes which the filmmaker profoundly dealt with in the latter part of his career (1950s & 60s). The simple plot revolves around two geishas – one middle-aged (Mitsuo Yoshikawa) and the other young (Sumiko Mizukubo) – who struggle to come to terms with the humiliation faced in the line of work and within the family.

The middle-aged woman, Kikue has a rebellious young son named Yoshio (Akio Isono). He resents her for the work she does. The younger girl Terugiko uses the camaraderie she has developed with Yoshio to make him see his mother’s sacrifices and travails. Naruse’s elegant staging clearly saves the narrative from wallowing in melodrama. His direction accumulates the smallest details to effectively construct an everyday portrait of the impoverished people. The nuanced performance of the beautiful Mizubuko also serves as the emotional fulcrum of the narrative.

Similar to Japanese Silent Films – PALE FLOWER [1964] REVIEW – A NOIRISH PARABLE WITH STRIKING IMAGERY

11. The Water Magician (1933) | Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

The Water Magician (‘Taki no Shiraito’) is one of the few surviving silent cinemas of Mizoguchi (the director made his debut a decade before, making five to ten films a year). The film tells the story of a 24-year-old Taki (Takako Irie), a famous water juggling performer, who is part of a traveling carnival. Taki falls in love with the penniless carriage driver Kinaya (Tokihiko Okada). She supports her lover and provides him money to finish his education at law school. However, the waning popularity of her act at the carnival forces Taki to take desperate measures in order to fund her lover’s dream.

Self-sacrificing female characters are a key feature in Mizoguchi films, even though these characters are developed with more depth and nuance in his later masterful works. Nevertheless, the brilliant imagery here shows Mizoguchi’s penchant for poetic framing.

Related to Japanese Silent Films – Watch The Water Magician Full Movie Here

12. Japanese Girls at the Harbor (1933) | Director: Hiroshi Shimizu

Even though relatively unknown in the West like his contemporary Yasujiro Ozu, Hiroshi Shimizu had a long and successful career in Japan, directing some of the most stylistically brilliant character studies in Japanese cinema. Japanese Girls at the Harbor (‘Minato no nihon musume‘) is a simple character piece about a pair of school girls (Sunako and Dora), living in the seaside town of Yokohama. They are best friends and are attracted to a handsome young man from the same area. Despite a thin narrative, Mr. Shimizu’s mise-en-scene (that is decidedly modern for its times) manages to subtly evoke the characters’ yearnings and their stifled existence.

Similar to Japanese Silent Films: 25 Feel-Good Movies And Where To Watch Them

13. Every-Night Dreams (1933) | Director: Mikio Naruse

This silent cinema shares the narrative and thematic threads of Naruse’s previous film, Apart From You. The protagonist is a poor, strong-willed woman (Sumiko Kurishima) who works as a Ginza bar hostess to raise her little son. Her deadbeat husband has left them a few years before. The single mother although doesn’t like working at the bar actually proves to be quite good at the job. Her life is disrupted when her husband reappears. Every-Night Dreams (‘Yogoto no yume’) was one of the most stylistic works among Naruse’s silent-era films, as we witness here the heavy use of dramatic zoom-ins and montages. He perfectly attunes to the increasingly distressing situations the central character finds herself in; the wordless yet meaningful glimpses sharply convey the woman’s mental state.

Also Read: Repast [1951] Review – A Wonderfully Subtle Marital Strife Drama

14. A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) | Director: Yasujiro Ozu

As Donald Richie wrote, “Yasujiro Ozu, the man whom his kinsmen consider the most Japanese of all film directors, had but one major subject, the Japanese family, and but one major theme, its dissolution.” In this silent classic, Ozu explores the itinerant life of an aged traveling actor who reconnects with his long-ago mistress and meets his now-grown college-going son. The son doesn’t know the actor is his dad and only calls him ‘uncle’. The actor’s current lover, embittered by his antics, conceives a plan to destabilize the son’s life. Although the plot sounds off like a loud melodrama, Ozu imparted marvelous nuances to his characters.

The breakneck pace of early Ozu silent cinema is completely replaced here with carefully composed static shots and low angles. The filmmaker revisited the same premise in 1959, which only deepened the narrative structure, thanks to Ozu’s more stream-lined disingenuous visual style and his deft handling of post-war themes.

Also, Read: 10 Best Tony Leung Chiu-Wai Movie Performances

15. An Inn in Tokyo (1935) | Director: Yasujiro Ozu

An Inn in Tokyo was Ozu’s last silent film. Similar to Passing Fancy and The Story of Floating Weeds, this also deals with the lives of lower-class Japanese, who were heavily burdened by the economic depression of the 1930s. The films were also termed as ‘Kihachi’ series because of the recurring name of the protagonist (all played by Takeshi Sakamato). An Inn in Tokyo revolves around Kihachi and his two young sons, Zenko and Shoko. He walks around Tokyo looking for a job and worrying about feeding his children. On the road, he meets a young widow Otaka and her little daughter. Kihachi befriends the single mother and later finds a job through an old friend. Yet things take a bleaker turn.

Episodic and quite restrained, this film has almost all of the Ozu-esque elements which he more keenly focused starting with his first sound film The Only Son (1936). A vast area of barren wastelands and shadowy interiors, Ozu’s aesthetics here is exactly opposite to what we witnessed in the cheerily optimistic I Was Born But… (1932).