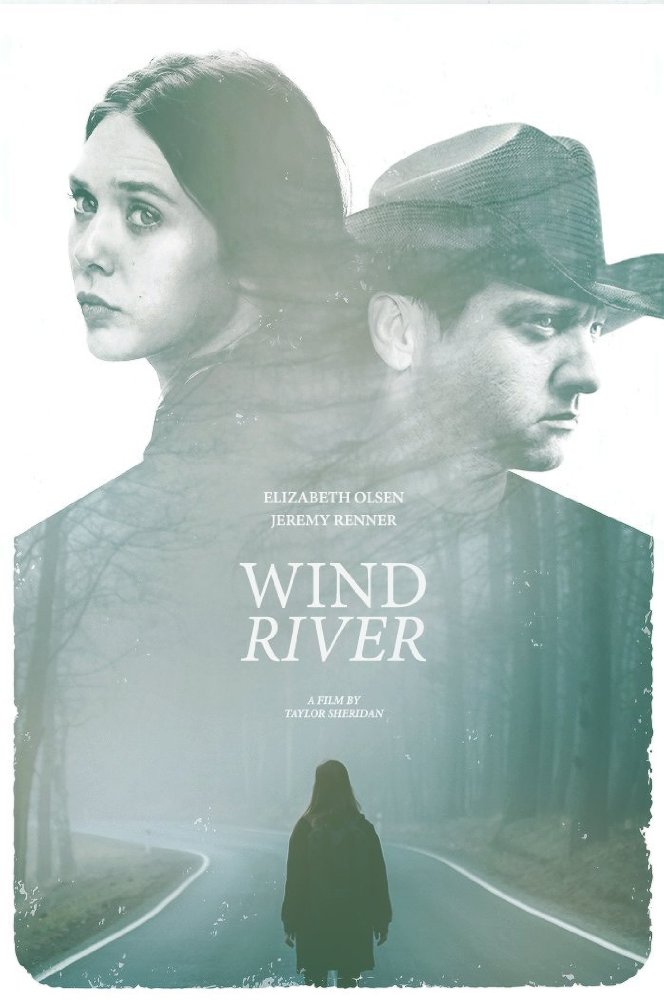

Wind River [2017] : A Simple Mystery Thriller Incorporated with Fine Emotional Terrain

The ascension of 47 year old TV actor-turned-screenwriter Taylor Sheridan in Hollywood has become the stuff of legend in the contemporary American cinema: Three spec scripts converted into three critically acclaimed crime fictions. Despite having never penned a script before, Mr. Sheridan is said to have finished the three spec scripts (a script written with a hope that it will be purchased by a producer or a studio) within six months and sold two of them immediately. One was Sicario (2015), helmed by Denis Villeneuve, which explored the drug war in US-Mexico Border. The next was neo-Western Hell or High Water (2016) which contemplated on the economical despair of West Texan residents. Sheridan preserved the third script – Wind River—hoping to take over the directorial rein (considering the success of Sicario & Hell or High Water, Sheridan naturally became contender for the directorial position). Wind River (2017) is set in frigid Indian Reservation in Wyoming. Clubbed together, these three films form the loose ‘American Frontier Trilogy’.

Taylor Sheridan diffuses set of values and recurring character traits into his unofficial theme-driven trilogy. Strong-headed women turned vulnerable by violent circumstances, anguish-ridden good-hearted & honorable men, examination of America’s marginalized community, overhead shots of harsh landscape, foreboding set-pieces unearthing American underbelly, and confluence of genre elements, social conscience and emotional truth are all predominant threads that’s at play in Taylor Sheridan’s universe. In fact, the prologue of Wind River reminds us of the writer/director’s wolf and sheep analogy in Sicario. A young, bloodied Native American girl runs barefoot, in the middle of night, on the snowy landscape, before collapsing on the ground and dies with a whimper. Sheridan’s eye for atmospheric detail and procedural once again upholds our interest in what otherwise seems to be simple murder/mystery that starts with a mutilated body. Cory Lambert (Jeremy Renner), an officer of the Fish and Wildlife Service stumbles upon the body while following a family of mountain lions that’s hunting down domestic livestock.

Writer/director Taylor Sheridan, in his interview to Rolling Stone Magazine, remarks ‘how doing bit parts in procedural television has allowed him to study its basic structure and its limitations’. While the central mystery weaved by Sheridan is imbued with certain generic elements, he attempts to transcend the alleged constraints by scrutinizing the community’s ostracized status rather than simply use the wintry lands as idiosyncratic backdrop. Sheridan says it is why he took over direction since he was worried that any hired film-maker may eschew the issues faced by Native Americans to highlight two white American’s heroics. It is true that Sheridan has treated the reservation inhabitants with respect and pondered over the issues with sensitivity. But there’s a feeling that it’s overwritten and certain directorial choices seems a bit on-the-nose, lacking the visual acuity of Denis Villeneuve or David MacKenzie. For example, the scene towards the end when Lambert laments on hardships of living in the res with dull platitudes (the writer sneaks-in wolf remark too) to Jane or an earlier scene when Lambert explains to Martin on facing the grief of losing a child. The words, of course appear to be well-penned, but it doesn’t do much in terms of visuals or deepen the characters or at least move forward the plot.

The missteps, however, is understandable taking into account that this is Sheridan’s full directorial debut (he worked as director-for-hire in the mediocre independent horror Vile in 2011). And, Sheridan cooks up few interestingly powerful and subtle visual compositions. Although the backstory which solves the mystery is as elementary as depicted in cheap crime fictions, the director frames the sudden escalation into violence in a very haunting manner. While the blurred vision shoot-out in the dilapidated house of young Native American verges on gimmick (the action combines the tense opening shoot-out in Sicario and final pitch-dark sequence in Silence of the Lambs), the build-up to the bloody encounter between private security forces at an oil company and the police force was sharply executed. Even though Sheridan showcases an act of revenge and vigilantism in the end, he keeps an artful distance so as to shun the viewers from anticipated catharsis. The director rather chooses to finish the narrative with a simple yet very thoughtful final shot: a Cowboy and Indian who in the past centuries had fought on opposite sides, sit side by side, indifferently gazing at the vast landscape, and share their inner pain and heartbreaks in that lingering, unforgettable moment. This shot effortlessly convey the agony and grief of America’s most marginalized than the earlier barrage of words.

With Wind River (110 minutes), writer-turned-director Taylor Sheridan moves from volatile, sweltering lands of Sicario and Hell or High Water to a frozen yet equally precarious atmosphere of Indian Reservation. The mystery plotting at its centre remains very economical and familiar, but the narrative gains strength through its honest inspection of contemporary Native Americans’ lamentable existence.

★★★½

New Republic Review

Director Taylor Sheridan Interview — Globe and Mall

Taylor Sheridan Interview — Collider