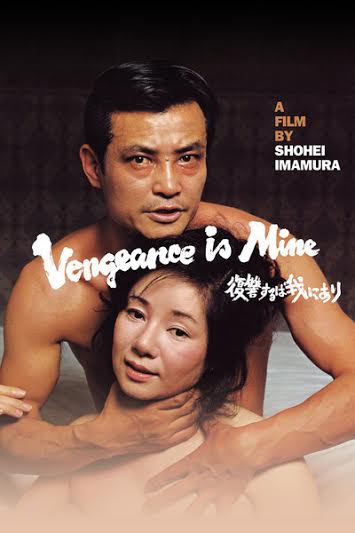

Shohei Immamura is one of the important film-maker in the ‘Nuberu Bagu’ aka ‘Japanese New Wave’. The masterful director of Post World War II Japan often unsettled his viewers by exploring and some times exposing the intricate and dark layers of oppression in the civilized society. His protagonists were mostly poverty stricken, criminals, social outcasts, pimps, black marketeers, etc who were approached with exceptional objectivity. These protagonists often question the advised moral values of the modern society and through their suffering we could grasp the denial of societal freedom and democracy. Immamura directorial style reached a point of excellence with his 1979 irate feature-film Vengeance Is Mine – his first full length movie in over a decade (after “The Profound Desire of the Gods” in 1968). The screenplay based on Ryuzo Saki’s biographical novel chronicles the 78 day man-hunt of sociopath/swindler Akira Nishiguchi. The name, however, was changed to Iwao Enokizu (astoundingly portrayed by Ken Ogata) and Immamura uses ‘Iwao’ as the perfect allegorical element to depict the residual creatures of modern society, whose disturbing, perpetual crimes has an intricate link with the ideological and economic decadence in the society.

Vengeance Is Mine opens with Iwao Enokizu traveling in a car with police detectives on a desolate, mountainous snowy terrain. He has been caught after 78 day search and during the period he has swindled lot of money and murdered five innocent people. In the car, Iwao muses about how he isn’t going to live to a ripe old age, since capital punishment looms in front of him. “Its gonna be damn cold in the clink” says Iwao as the movie’s title plastered on-screen, accompanied by a brassy musical track, which seems to belong to old, black-and-white thrillers. This initial scene also makes us think of the Richard Brooks’ true crime masterpiece “In Cold Blood” (1967), where two traumatized, avaricious individuals kill an innocent family. But, Immamura’s courageous film couldn’t be accommodated within the frameworks of neither a conventional thriller nor a true crime feature. Why? Because we are never offered the answer to what makes Enokizu to kill people? Or what served as the roots for his sociopathic tendencies? The detached, objective frames of Immamura offer no evident moral core and the wild jumps in narrative keeps us in a confounding mindset. At least, “In Cold Blood” we had that brilliant moment, where the light shines through rainy window as Perry Smith soulfully talks about forlorn dreams. As Mr. Roger Ebert perfectly states “What’s disturbing about Enokizu is that he has no feelings at all about his victims”.

Iwo Enokizu isn’t brilliantly evil like Hannibal Lecter, Dr. Mabuse or John Doe. He doesn’t have a despicably twisted mind too, like Norman Bates, Zodiac killer or the Leather-face. Iwao just hails from a simple, middle class family with a loving mother (Mayumi Ogawa), religious father (Rentaro Mikuni), a compliant wife (Mitsuko Baisho) and two beautiful daughters. The multiple flashbacks in the narrative exhibits Iwao’s childhood delinquency, his brief stint with the imperial army, hatred for his father, and the subsequent loveless marriage. But, such sequences are scattered throughout the film like small pieces in a larger puzzle set, and are captured with an objectivity that doesn’t offer any straightforward answers. The time-jumping narrative also ponders over the lurid thoughts and actions of the people around Iwao. Iwao’s father is a hypocrite, who has feelings for his daughter-in-law Kazuko and tries hardly to suppress those thoughts. Kazuko tries to seduce her father-in-law and at one occasion openly states that they could be together after Iwao’s hanging. She is forced to sex by an acquaintance of her father-in-law. Kazuko, initially opposes the man’s actions, but when he says that ‘he has the blessings of her father-in-law’, she gives in and passionately embraces the man, emitting the word ‘father’.

While on the run, Iwao stays in a rundown inn, managed by a downtrodden woman Haru (Mayumi Ogawa). She is a kept woman of the fraudulent, oafish inn owner. Haru’s ailing & gambling mother (Nijiko Kiyokawa) has murdered a man after the World War and often peeps at the sexual escapades of her daughter and those of others, staying at the inn. Haru develops a relationship with Iwao Enokizu, although he is more interested in intercourse than reciprocating her love. Iwao’s also sees Haru’s mother like a ‘buddy’, since she know how it feels to kill. In one excellent conversation between Iwao and Haru’s mother, she tells “I felt great when I killed the old battle-ax. Is that how you feel now?” ‘No’ replies Iwao. “So you haven’t yet killed who you really wanted to kill?” asks the mother. ‘May be not’. To which the mother says “Then you’re a wimp”. Later, the boorish inn owner rapes Haru in front of her mother and Iwao in the other room thinks about killing the man. However, they both do nothing. At last, Iwao, waiting for death penalty, was visited by his father. Iwao states how much he wished to kill his father. In fact, the central character never kills people out of deep impulse. And, when the police are interested in the motive, Iwao simply tells them that he committed the crimes and deserves to die.

Shohei Immaura instills forceful blows on viewer’s mind from two points: In the way, he stages the killings of Iwao; and the manner with which the so-called normal people, surrounding Iwao, repeatedly crunch the basic human values. By hinting at the murderous, illicit sexual fervor of others in the constrained society, Immamura doesn’t try to create sympathy for Iwao. What he indicates is the sociopathic tendencies arising out of a rigid society, where life takes a humdrum routine. While most of us turn our rage inwards and become an emotional wreak, Iwao turns it on the society itself. Like the steam that arises from hot-spring inns (Iwao’s father owns such an inn), are the killings a way to relief for Iwao? Psychopaths or sociopaths are often defined as deranged loners or seem to have a sexual dysfunction. Iwao has neither of those. He with his chameleon-like attitude attracts people to believe in him and his face is so common in the crowd that many people, even after seeing the face in ‘wanted posters’ fail to recognize him. The sexual hunger of the character also doesn’t stand out when compared with the feelings of pious father or that of the inn owner. Nevertheless, amidst all this ambiguity, Immamura catches us off-guard, when showcasing Iwao’s pure monstrosity, which is the detailed staging of the murders.

After the initial scenes of police interrogation, the narrative jumps to show the first two murders committed by Iwao. Director Immaura buries the memory of these murders into our mind to evoke it at later points and without these scenes Iwao the smooth con artist could elicit sympathy from viewers. We see Iwao in a workers’ uniform, ditching the bicycle and hitching the ride with two truck drivers of his company. He makes up a story about booze and takes the older one of two into a remote place and repeatedly hits the man in his head. Later, Iwao urinates at his hand to wash away the blood, buys knife at a shop, and then coolly leads the other one to a remote spot, stabbing him to death. The murders are messy. There’s blood all over and the men getting killed beg at Iwao. One says “please don’t kill me. I have a daughter to take care of”. But, Iwao remains detached during the whole act and steals the few thousand yens to start a new life. At another time, he befriends a lonely old lawyer, kills him and stashes the body at the man’s wardrobe. Iwao nails and tapes the wardrobe’s loose door. He gets angry and leaves the place, when he couldn’t find out the can opener, but never shows any signs of rage about killing the man. May be we could say that Iwao had distaste conformist individuals and so chose to murder these three men. But, the next two murders really unsettle us, because they both (Haru and her mother) understood him and Iwao showed some respect for them.

Immamura is famous for his unobtrusive camera angle, which inspired many other film-makers of the Japanese new wave. In this film, the shots are placed often above eye level (some times hangs from the ceiling) or else placed at a distance for the perfect objective perspective. Mr. Ebert indicates at the significant absence of quick cuts in Immamura’s works. Vengeance Is Mine is a challenging film from the start since it couldn’t be classified. With every turns in the narrative, Immamura chuckles at us for hoping to find meaning from human actions. The director wants to show how exclusion or classification can never solve a problem (Iwao is excommunicated by the church and the father excommunicates himself for having amoral thoughts about his daughter-in-law). Immamura implies how societal restraints and conventions are just superficial things, created solely for economic gains, which in turn devours the basic human values and aspirations. In every way possible, this is a cinema of defiance. This defiant quality is not just entrenched in the characterization of Iwao Enokizu, but also in Immamura’s playful directorial touches. For example, in the ending sequence, Iwao’s father and wife throws away his remains from a mountaintop. As they throw the remains, it freezes in mid-air. This darkly humorous defiance indicates how Iwao isn’t going to go away easily from his family’s memory, or in a broader stroke, it may indicate how the manhunt and state-sanctioned killing of a sociopath didn’t change anything in the corrupt society.

The vision of chaotic evil and violent nihilism in Vengeance is Mine (140 minutes) discomfits a viewer like no other film in the cinematic history. Iwao Enokizu isn’t condemned nor his murderous activities elevated to a myth, and even the society that created him isn’t bluntly blamed. What we gaze at is a pure, dark, subversive force that offers no meaning.