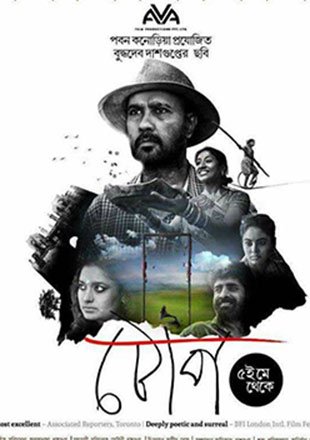

There was a time when a Buddhadeb Dasgupta film would be welcomed with as much gusto as a Rituporno Ghosh or an Aparna Sen film. The last time that happened, was perhaps with Janala (2009), which was bogged down by stiff performances from the lead cast. While Ghosh and Sen continued to grow in the Indian cine goers consciousness, Buddhadeb Dasgupta simply faded away somewhere – so much so that an evening show of his latest picture, Tope – The Bait, could hardly muster up ten patrons on a Friday evening showing on the day of its release. Don’t beat yourself up over being caught unaware of this latest offering, because so was I.

Not that Buddha babu has anything to worry about – he is, as the common parlance goes, a ‘darling of the festivals’. Tope itself has notched up impressive returns from half of the world’s A-list film festivals including Busan and Toronto where it premiered as a part of the festival’s ‘Masters of World Cinema’ sidebar – a fact that the filmmaker did not forget to mention at a press conference held during last year’s Kolkata Film Festival.

Nonetheless, the fact that his own people may have forgotten him does not seem to be lost on the master filmmaker – as was evident by his self-conscious tone when announcing that Tope was his first film in two decades to warrant a screening at the Kolkata Film Festival. One might call it poetic justice then that Buddhadeb Dasgupta returns to the Bengali screen after a hiatus of eight years with a story that romanticises the beauty of being lost – for Tope is, ultimately, a film about just that – getting lost. Tope’s world consists of a king who is lost without his kingdom, a teenage street performer who is lost without her childhood, a postman who is lost without his mind, and indeed a land which is lost in time.

In the same KFF interview, Dasgupta had spoken about being obsessed with Narayan Gangopadhyay’s short story for years before he felt like he could film it – reason being that he felt that the story was too realistic for his universe. But Tope is not a realistic film at all – it is soaked in Dasgupta’s distinct style of magic realism – so much so that when one walk’s out of the film, the real world seems to pale in comparison to its depth and richness, it seems too mundane and one-dimensional to be interesting. Every frame in Tope’s world – whether it’s the oft-repeated motif of bodies and objects floating around in a swampy pond or the simple yet breathtaking moment when the spatial enormity of Goja’s tree is revealed to us through clever camera work – is filled with disdain for all that we can consider ‘real’. Here, Asim Bose’s genius cinematography goes miles in creating moment after moment which at once pull us into this dreamlike world while still reminding us constantly that reality is only a curtain pull away. Bose’s work cannot be mentioned without Alokananda Dasgupta’s hauntingly beautiful background score for it is only when these two come together to create a bizarrely beautiful cinematic melody that Tope seizes to be just another story of class struggles from rural India and becomes something that will resonate in the minds of the audience for some time to come.

It has become fashionable of late to liken cinema to ‘poetry’ or ‘a painting’, but one look at Tope and we are reminded that cinema cannot be equated with any of the art forms that preceded it for it is truly an amalgamation of each of those art forms. Tope’s visual design is whimsical like a painting, and yet blunt in its depiction of humanity, like photography; its sound design and music equal parts of dramatic and symphonic, and its narrative lyrical in tone and poetic in the manner it unfolds on screen. Like most masters in the ultimate arc of their filmography, Buddhadeb Dasgupta has mastered the art of master-shot taking. On closer look, the film is a series of long takes which are so dynamic and cut with such precise fluidity that not once does the pace of the film bear down on the viewer.

While the film’s characterizations are nuanced and the screenplay pacey, revealing, and replete with dark humour and political undertones if only one chooses to look beneath the surface, the cast fails to bring much resonance to their parts. As is the case with many films in Dasgupta’s repertoire, acting proves to be the Achilles heel in Tope as well. Barring the two naturally gifted leading ladies – Paoli Dam as the mother of a wandering street performer, and Ananya Chatterjee as Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s version of a bored and lonely housewife, the rest of the cast is not only unconvincing but in fact oscillating between needlessly loud and utterly cold. Super urban Chandan Roy Sanyal is miscast as the insane (or is he the only sane one?) postman who has stolen the entire village’s letters and made his home amongst a brood of moneys. He tries his level best to breath life into what is the easily the best written part in the film, but he is simply not good enough an actor to pull it off. The real revelations of the film, though, are little Kajal Kumari who brings a confidence and finesse to her portrayal of a street performer who longs to meet her prince charming that is rarely ever seen in child actors, and Sudipto Chatterjee as the maniacal king without a kingdom who breaks into childlike song and dance at the drop of a hat with the same gay abandon with which Dasgupta’s screenplay hurtles towards its tragic climax.

Buddhadeb Dasgupta had once famously quipped, “One can make a movie without giving too much of an importance to the art of story-telling.” While that may be true for his particular brand of magic realism, the logic falters when brought out into the real world – and that is where, sadly, Tope looses the plot. The climax of the film, where a wounded mother, her husband, and the goofy postman set out to vengeance a despicable atrocity by the mad king, strays into reality and thus fails completely. In the end, Dasgupta tries to tie things up all too abruptly and ends up denying the audience a satisfying conclusion to this wondrous journey