The development of Chinese cinema is generally compartmentalized into six unique generations of film-makers, starting from the year 1905 (the year first Chinese film was made) to the present. Among these the fifth generation film-makers were considered to be the most influential and popular group. The triumvirates – Zhang Yimou, Tian Zhuangzhuang, and Chen Kaige — of this film-era began their studies (in Beijing Film Academy) and entered into the industry after the end of Chinese Cultural Revolution. They grew up during the chaotic social movements which gave their films a distinct perspective. Although the time of fifth generation film-makers were considered to have partially ended before the 1990s (after Tienanmen Square protests of 1989), some of these film-makers’ greatest works were made in the early 1990s, The sixth and post-sixth generation directors too followed their predecessors’ way of making films outside the Chinese film system (often engaged in confrontations with censors). Among the fifth generation film-makers, Zhang Yimou is a very popular name among the international art-house movie-lovers. His oeuvre could be easily distinguished between the works made before and after 1994. Yimou’s early films like “Red Sorghum” (1987), “Ju Dou” (1990) criticized both the absurd old, traditional values as well as the oppressive, contemporary social system. His early works were often disapproved by Chinese critics and censors, blaming him for confirming the Western image of China (as poor and backward). Nevertheless, Zhang Yimou’s portrayal of the Chinese society never relied on caricatures; it often shines with humanism and hope.

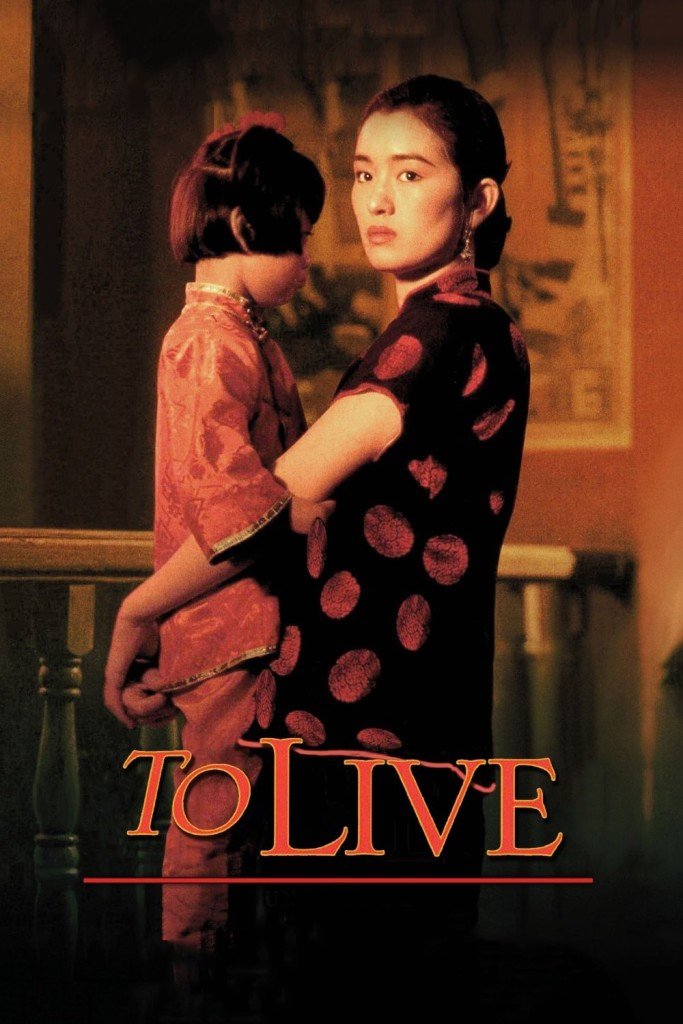

In 1994, Zhang Yimou adapted novelist Yu Hua 1992 novel titled To Live aka “Huo zhe”. It is a significant movie for brooding on a politically sensitive topic and also happens to be the last film before Zhang Yimou made a transition in his film-making style. Upon its release, To Live was immediately banned. Although it won the year’s Grand Jury Prize at Cannes, the film was never released officially in China. Later, Zhang wasn’t allowed to receive foreign funds for the production of his movies. He then opted to make conventional, non-politicized films like “Shanghai Triad”, “The Road Home”, “Happy Times”, etc (To Live was the last of Zhang’s movie to be banned in China). Two of the critically and commercially successful ventures – “Hero” (2002) and “House of Flying Daggers” (2004) – brought him back the international fame. His refined cinematic language added dazzling quality to those martial arts films. The trailer of his upcoming CGI extravaganza “The Great Wall” simply introduces Zhang Yimou as a ‘visionary’. I do love the sumptuous visual treat he has offered in the past decade or so, but I mostly prefer Zhang Ymou, the preeminent, sociopolitical film-maker.

“To Live” chronicles the hardships faced by a family for more than three decades, from the Chinese Civil War to Cultural Revolution. Yimou makes a sweeping & sharp examination of the Chinese revolution through the life experiences of the ordinary people. The melodramatic contrivances in the plot and the light-hearted take on the source novel were generally criticized. But after plenty of repeated viewings, I must say that To Live has never ceased to amaze me, providing one of the most touching and thought-provoking movie experiences. The film often takes a melodramatic turn without being wholly dramatic or insipid. The way Zhang Yimou contextualizes the country’s sociopolitical history through the eyes of these ‘salt of the earth’ people is a wonder to behold. Neither the characters are reduced into hero/villain categories nor do they serve only as a mouth-piece for director to spew his ideologies. Apart from being a human drama and a critique on Mao’s regime, To Live also possesses existential themes. What does the phrase ‘to live’ means to these ordinary people, whose greatest joys comes in very little doses, encompassed inside the never-ending day-to-day struggle.

The film is set in Yimou’s favorite small town setting. He is a genius when it comes to adding copious amount of little details to life of people, habituating in small towns. The movie opens on a narrow stone street, riddled with traditionally built mansions, taking us back to the waning days of Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China (after the end of World War II). Xu Fugui (Ge You) is a landlord who leads a debauched life, spending whole night in a local gambling house. After a long night of gambling, he is carried by a female servant. Fugui’s compulsive gambling had led him run up a vast ledger of debts. At home, he scowls at his wife Jianzhen’s (Gong Li) protests. Fugui’s parents are too old to control their son. One day the gambling debts run up to a point, which forces Fugui to sell-off their ancestral home. As he is tossed into the street, his pregnant wife leaves him, taking along their little daughter. Fugui’s father dies, unable to cope with his son’s vile, self-indulgent behavior. When Fugui becomes a changed man and starts to work on the streets (as a puppeteer), his wife returns back with their little son Youqing and daughter Fengxia. Nevertheless, tragedy follows him as he is forcefully drafted into military (first forced to serve under National Revolutionary Army and later under Communist Red Army) during the 1949 Chinese civil war. When the war is over, Fugui returns to his family to begin a new life under the new people’s government.

Ever-smiling, little Fengxia has lost her voice to a high fever. But, their life is far better and looks promising. The new government has given Jianzhen the job to deliver water and the local communist party leader of the region is a genial man. The focused, energetic local bunch are working towards the party’s goal of communal happiness. Fugui witnesses the execution of the man who has newly occupied their family’s ancestral home. The guy was killed publicly for being a landlord and disapproving the communist regime. Panic-stricken Fugui returns to home and tells his wife that they are now lucky to be part of poor, working class. He also frames the certificate he received from the Red Army to totally discard their landlord past. The narrative then shifts to two vital time frame under Mao’s rule: The Great Leap Forward (between 1958 and 1961); and Cultural Revolution (commenced in 1966). Fugui’s family faced little joys and countless tragedies during that totalitarian era, when the rulers annihilated the existence of private space and individual happiness. Even though, Fugui and Jianzhen are repeatedly caught in the storm, stirred by sociopolitical changes, their innocent souls withhold hope for the future. The sense of being together as a family gives them the need ‘to live’ than the alleged ideological framework proposed by their non-personified oppressors.

Most of Zhang’s movies from the late 1980s and early 1990s present traditional Chinese elements (related to its culture). The old shadow-puppet play is used in “To Live” to track down each of the transition period in Fugui’s life. From the earlier days, he plays puppets for fun to the day it all are burnt, the puppets serves as the passive elements, bridging his past to the present. The puppets reinvigorate Fugui’s purpose in life at different times. The aesthetic sensibilities of Zhang makes us a participant (may be passive) than being a disconnected observer. Zhang’s examination may not be original or less subtle, but there’s honesty in the way he presents his characters and contextualizes their joy and pain. Despite grounding the characters and events in a realistic environment, Zhang’s narrative does embrace few melodramatic ideas. Even in those circumstances, he immerses us deep into the characters’ viewpoint (the credit also goes to these great performers) that we can’t do anything but react to their struggles. He humanizes the on-screen melodrama to a point that it looks like an unforced drama, flowing with humanity. His art form is so unforgettable and smoothly flows through which allows him the space to perfectly incorporate his personal idealism. To Live isn’t the darkest drama the censor officials thought it was. Director Zhang diffuses his frames and narrative with many subtle elements. There are a lot of comedic moments, like when Fugui rushes to his wife after the execution of a landlord or when precocious kid Yongqing teaches a lesson the bullies. The imagery of Mao and the red color increasingly permeates throughout the narrative as the difference between private and public space keeps on blurring.

Perceiving “To Live” only as a sentimental drama, set in the era of Chinese communism, would stop us from connecting with many of its subtleties, metaphors and acute ironies. I have personally experienced or found something new every time I watch the existential quandaries of Fugui family. It is true that Zhang’s film isn’t as scathing or subtle as the examination of the same era by fellow fifth-generation film-makers Tian Zhuangzhuang (in“Blue Kite”) and Chen Kaige (in the Palme d’Or award winning “Farewell, My Concubine”) – both these masterpieces released a year prior to To Live. Nevertheless, Zhang’s brand of humanistic film-making has struck me deeply. Contrary to the Censor’s opinion, To Live isn’t an anti-communist film. Zhang takes a neutral approach to showcase what it means to live in that period. The camaraderie of the townspeople, the citizens trusting their leaders and the leaders respecting the common people are some positivity of the ideology that was later pervaded with paranoia and fear. Everyone’s work and achievement are recognized in those periods when Mao called up for the “The Great Leap Forward”. On the other hand, we see how the ideology’s amalgamation of private sphere into the public sphere affects individual’s decisions. The prioritization of individual thoughts over the alleged collective goodness intermingles with every affair that confounds Fugui and his family. There’s a sense of irony in how Fugui’s lucky turn to be a part of the proletarians (by gambling away all his properties) brings tragedies to him at every turn. In fact, the oppressive regime plays an indirect hand in the two key decisions (that shapes the eventual fate of his son and daughter) taken by Fugui. This blurring of private and public space under Communist regime also makes me think how much of the decisions we make (in our democratic, capitalist system) is influenced by pressure from public sphere (are we really free to decide, unlike those by-gone era’s Chinese people?).

To Live isn’t a story of staunch revolutionaries believing in everything the new authority put forth on them. Even the loyal follower of Mao, Wan Erxi (Fugui’s son-in-law) behaves in a practical, humane manner when a problem arises. The basic reason behind people struggling together as a commune is not because they have learned Communism overnight. Fugui and others are totally clueless about their allegiance to this new ideology. They approach it with hindsight and with a hope that it will better their lives. This particular approach to the characters makes us easily relate with them. We might be fascinated by a rulers’ rhetoric or a government’s policy, but in the end all the individuals and communities (with conflicting opinions) desire is a promise for good life. Apart from the propaganda speech uttered by the good-hearted Mr. Niu, the common people didn’t cook and slept with their families on streets for crusading against Western Capitalism. They believed it will eradicate the sufferings, at least for their children and children’s children. Zhang Yimou pays tribute to the great sacrifice of these people (without taking guns to the borderlands). There’s something commendable about those Chinese people who believed in the togetherness of family and community, never reaching out for blind ideological or religious support. Zhang beautifully symbolizes the failed desires of the uprooted young through simple things like ‘dumplings’ & ‘photographs’. In the final scene, when Fugui talks to his grand-kid Little Bun, the director uses chickens to symbolize the hope for future generations, built on the strenuous effort of previous generations. Even those who aren’t aware of Chinese history or not interested in its political message can relate it with the struggles faced by predecessors to provide a stepping-stone for the future generations (not just exclusive to Chinese people).

Ge You deserved the Best Actor Award he won in the 1994 Cannes Film Festival. This film marks the sixth creative collaboration between Zhang and Gong Li (their personal relationship waned after “Shanghai Triad” (1995)). Both the actors are stunningly naturalistic. The narrative offers us brief snapshots of the family’s 30 year life, but you could witness the amazing weight they bring to their characters, as if we have lived closer to them, sharing those 30 years of hardships and joys. Gong Li’s performances in Zhang’s films are a sheer wonder to behold. It’s a big challenge hold back the tears in the scene (every time I watch) when she breaks down in the hospital, holding her daughter in the hands. The three actors who play innocent Fengxia at different life stages are perfect choices. Perhaps, the greatest aspect of To Live is Zhang and his magnificent ensemble’s expert skill to make us fully perceive the reality faced by the on-screen characters.

In my humble opinion, To Live aka ‘Huo zhe’ (132 minutes) is one of the greatest & wisest family dramas ever made. The vital historical context and the overt as well as subtle sociopolitical messages are well balanced with rich and intricate human drama.

★★★★1/2