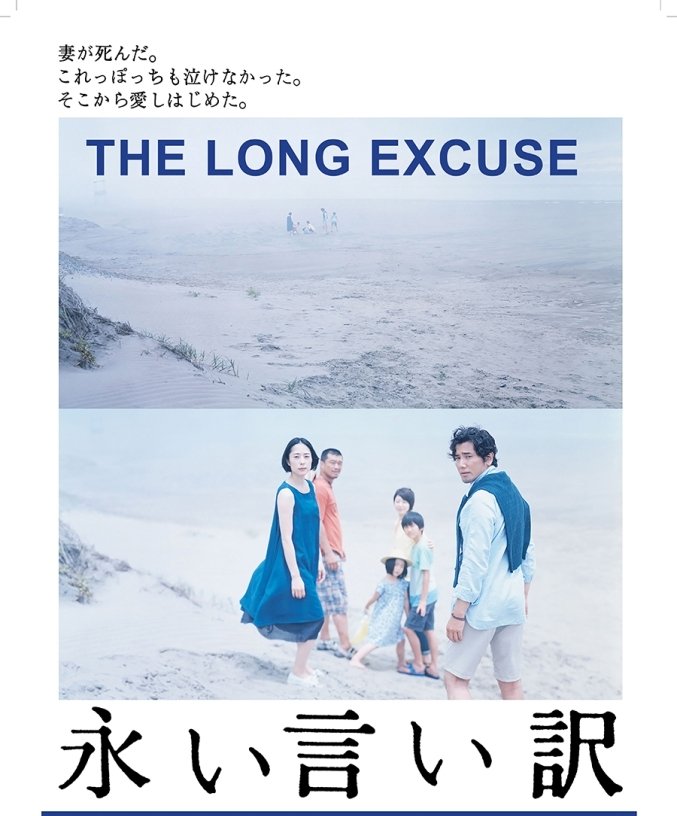

Japanese film-maker Miwa Nishikawa’s protagonist Sachio Kinugasa (played by Japanese star Masahiro Motoki) — in her heart-warming drama The Long Excuse (2016) – is a difficult personality to like. In a casual sense, you could call him as ‘asshole’ or a ‘jerk’. When we first see him he is drunk and getting his hair cut; not in a salon, but in the hands of his compassionate wife Natsuko (Eri Fukatsu). She bears her husband’s denigrating comments with a smile. From the tidbits of conversation, it’s understood that Sachio is a best-selling novelist, popular enough to frequently appear in TV shows, and his wife Natsuko, whom he had met before he was a writer and encouraged him to pursue writing career apart from taking care of all his basic needs, works as a hairdresser. Sachio chastises Natsuko for everything, even for calling him by first name among the public. Sachio’s petulant behavior continues up until Natsuko leaves him for the pre-planned trip with her best friend Yuki. As Natsuko and Yuki travel in a bus that zig-zags upon the icy mountainous road, Sachio is on top a young woman, reaping the benefits of his wife’s temporary absence. Alas, in the same time Sachio plunged deep within her, Natsuko’s bus caught in a blizzard, plunges into the icy lake. The absence is now permanent. Sachio is left to contemplate his own emotional frigidness alongside the irredeemable loss of a two-decade companion.

Miwa Nishikawa is one of the important modern Japanese film-maker and novelist, whose films take the middle ground of commercial and art cinema. The Long Excuse (aka ‘Nagai iiwake’) is the second time for Nishikawa to adapt her own novel (previously she wrote the novel Dear Doctor and made into a movie). Miwa Nishikawa has a degree in literature and in the last year of studies, she worked as assistant for internationally renowned director Hirokazu Kore-eda (in Afterlife, 1998; Mr. Kore-eda also graduated from the same university as Nishikawa with a literary degree). Later, in 2003 Nishikawa made her feature-film debut Wild Berries (‘Hebi ichigo’), which was partly financed by Kore-eda. Since then Kore-eda has given few opinions or ideas on her films. Mr. Kore-eda’s style could be seen in the way Nishikawa sensitively handles her character plus in the manner she avoids unnecessarily dramatizing the narrative. Yet, within the five feature films (including Long Excuse – my favorites of her works are Dreams for Sale and Dear Doctor), Nishikawa have developed her own distinct story-telling sensibilities. The Long Excuse has incredible warmth and complexity for such a simple premise, although the film is bit overlong with epilogues solely targeted at our tear glands.

The good thing about ‘The Long Excuse’ is Sachio’s characterization. Struck by the enormous tragedy, he doesn’t immediately put himself in redemption mode. He still couldn’t free himself from the artificiality of his public persona. We hear Sachio soulfully narrating the importance of Natsuko in his life and the sacrifices she made for him. However, it’s seen that he has written those words for the funeral gathering and even emits fake tears. It doesn’t mean Sachio feels no amount of grief over the loss of his wife. He hasn’t yet found a way to express it. What also accompanies over Natsuko’s loss is the fear of a future, where he would have no one to genuinely love him. The idolators and acquaintances are leaving messages and only hoping for Sachio to write a novel or do a reality-show based upon his tragic experience.

While contemplating his moral complexity, Sachio gets to meet a truly tormented figure in the meeting held by Bus Company: Omiya Yoichi (Pistol Takehara), husband of Natsuko’s friend Yuki. Omiya, a simpleton with a truck-driving job, finds it hard to take care of his pre-adolescent son Shinpei (Kenshin Fujita) and fickle little girl Akari (Tamaki Shiratori). The chaotic abode of the Omiya’s is immediately visible and contrasts the neatly aligned space of Sachio’s house. Suffering a bit from writer’s block, Sachio thinks of helping Omiya, who has to travel for at least 2 days in a week. Soon, the two children learn to trust Sachio and he too enjoys their company (Sachio found children as a block to his career dreams despite Natusko’s wish). But, still we aren’t very sure for the reasons behind his baby-sitting aspirations. Is it for his comeback novel or a TV show? Nevertheless, as Sachio explains to his manager, he loves this paternal role. And, it’s not before long, the possessive, cantankerous side of Sachio shows up to complicate his relationship with the Omiya’s.

Director Miwa Nishikawa in her interviews has said that the seeds for this story were sown when she came across news reports of the great earthquake in Tohoku (March 2011). “I came to the realization that beneath the surface, perhaps not all the losses suffered were of the dearly beloved……. There must also have been many not-so-fondly remembered and bitter farewells as well”, says Nishikawa. Although, Nishikawa’s drenches her central character in shades of gray and delves into darker themes, there’s always a strong thread of humanity and positivity running within the narrative arc. In ‘The Long Excuse’, she once again offers a life-affirming experience without either minimizing or overly dramatizing the nature of grief. She nudges us to be more conscious of the love’s preciousness so as to not later get caught in the abyss of misery.

Director Nishikawa diffuses assortment of details on how different people grieve or mourn over the loss of their loved ones. Sachio’s grief is more self-centered and even allows it to be exploited for the sake of melodramatic shows. Hence, Sachio’s mourning often leads to arguments and fights (the image of Sachio fighting at a cherry blossom was sharply ironical). Omiya’s mourning is of a different kind. He is totally stuck in the period before his wife’s departure (often replays the last message Yuki left in the phone) that he finds it hard to move on. In the middle are the confused children, whose feelings of loss aren’t much visible to the adults. The beauty lies in witnessing how the loss of these mourning individuals collide and gradually lead to healing. Similar to Kore-eda or the great Ozu, Nishikawa uses changes in seasons as a metaphor for the changes in characters’ life. She also finds space for subtle humor when polarizing values of Sachio and that of the children confront each other.

The chief flaw in the narrative lies in the third act as Nishikawa prolongs the narrative to find a perfect ending. Considering the director’s good intention to not provide conventional answers to the complex themes, the film could have been 15-20 minutes shorter and yet more powerful. The performances are uniformly excellent. Masahiro Motoki, (Departures, The Bird People in China) in the initial portions, truly incites our anger by playing such a deceitful character. Later, he genuinely makes us feel his vulnerability and humanity so as to empathize for his plight. Director Nishikawa, similar to many masterful Japanese directors, has developed a perfect knack to work with child actors. The kid who plays Akari doesn’t seem to be performing at all. The natural erratic behavior of a child is just captured in a poignant manner.

The Long Excuse (124 minutes) touchingly explores the emotional thawing of a heady, grief-stricken individual. It may lack the profundity orchestrated by film-makers like Kore-eda. Nevertheless, the stellar acting cast and director Miwa Nishikawa’s decision to not overly sentimentalize the tale, offers an intoxicating movie experience.