“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

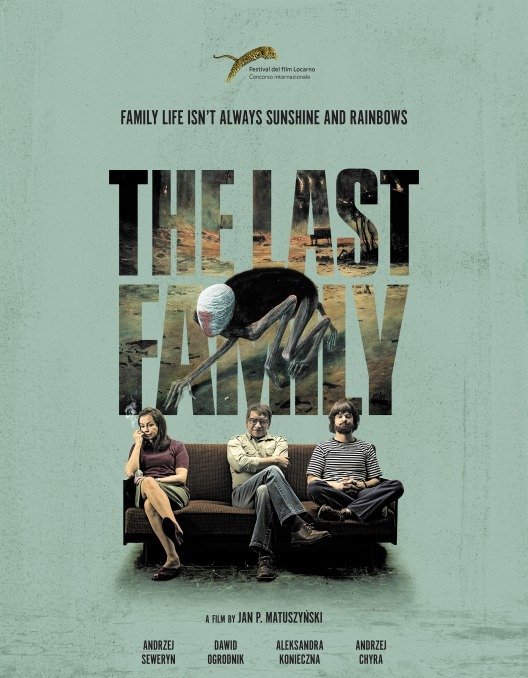

“You two are standing so far apart that I can’t capture you” says Zofia Beksinski to her husband Zdzislaw Beksinski and son Tomasz Beksinski aka Tomek, while filming them during a outing. This rather simple scene from Polish film-maker Jan P. Matuszynski’s feature-film debut “The Last Family” (Ostatnia Rodzina, 2016) suggests the complex, polarizing, yet fascinating stance of the genius father and son. The highly successful and controversial artist Zdzislaw Beksinski is well known for his surrealistic, Gothic painting works, which astoundingly addresses dystopia, death, and eternal suffering. His son Tomasz was a music journalist, pop music connoisseur, popular radio presenter and a movie translator. Both the father and son had a frigid perception of life and the world. Although Mr. Beksinski’s imagination took fanciful trips to darker alternate reality, he is a calm and amiable personality on the outside with a good sense of humor. But, Tomasz couldn’t master the ability to confine his darker side to his art. He was suicidal, manic-depressive and prone to sudden outbursts. Wife and mother Zofia Beksinski was the silent, solitary force who held the artistic family together. “The Last Family” isn’t a typical biopic that chronicles the idiosyncrasies of an artist through his art. Director Matuszynski neither recounts the tale or situation behind Beksinski’s famous paintings nor studiously portrays Tomek’s career. This story of Beksinski family is set between the years 1977 and 2005 and focuses on the bonds between these three polarizing characters. By observing the family’s quotidian life, Matuszynski gets closer to their struggles in life’s darkest corners.

Director Jan Matuszynski said in an interview, “This must be the best documented family ever in history”. From 1957, Mr. Zdzislaw Beksinski started recording his familial conversations on a tape recorder (a year before his son’s birth). From early 1980s, he switched over to VHS camcorder and later to digital technologies. He obsessively documented his intimate world — their trivial activities as well as fired up interactions. Script writer Robert Bolesto mined through the extensive family archives and made meticulous investigation on the family so as to boldly state that ‘the story is not a liberal interpretation, but rather a painstaking reconstruction of the everyday interactions of Beksinski family’. The director actually used the same cameras Zdzislaw Beksinski had to faithfully recreate the ‘domestic-video’ sequences.

The film opens in 2005 with Zdzislaw (Andrzej Seweryn) announcing his fantasy to biographer and friend Piotr Dmochowski. The fantasy involves a virtual reality programme that could cook up fine-tuned version of Alicia Silverstone with sadistic abilities. While it looks like an eccentric way of setting up the central character, it impeccably suggests how the acclaimed painter confined his misanthropy, obsessions, and helplessness to these virtual forms of desire or alternate reality. The narrative then moves back to 1977, the year Beksinski family relocated from their provincial hometown Sanok, Poland to an architecturally insipid high-rise in the capital city Warsaw. Zdzislaw, his wife Zofia (Aleksandra Konieczna) and their two ailing mothers live in one apartment. Tomek (Dawid Ogrodnik) lives alone in an apartment, in a high-rise situated at the extreme opposite to theirs. There’s no single mention of the Solidarity Movement or Soviet repression or any form of politics because the family lives in a zone, unbothered by the external influences. Beksinski senior is an isolated artist, devoted his self entirely to the art. And, he also devoted fair amount of time to observe his family and analyze their idiosyncrasies. Beksinski junior acquired a taste to appreciate different cultural trends – from pop music to cinema – yet he struggled with chronic emotional troubles and suicidal impulses.

The family atmosphere didn’t do much to help Tomasz. As Beksinski senior says about his son: “every tiny thing triggers an avalanche”. The genius father and son are fascinated as well as petrified by the suffocating reality. However, Tomasz couldn’t handle the ‘rock-bottom’ like his father, who possesses fine dose of humorous stoicism. On one occasion, Tomasz attempts to blow up his apartment and covered with blood, falls at the doorstep of his parents’ apartment. While director Matuszynski vividly chronicles their darker impulses, he doesn’t provide a sharper interrogation on the troubles of two males. It’s simply a meditation on these individuals’ inner worlds – on how it salvages and destroys itself. This approach may frustrate a lot of viewers because each casual or intense conversation resembles a funeral procession, devoid of simple meaning. Yet, this mature case study of life’s merciless nature and human’s unfulfilled desire worked for me. Its atmosphere of despair and stoicism was even oddly touching at times.

Jan Matuszynski’s directorial style could be called as detachedly observational (and slightly stuffy). He examines his subjects without judging or commenting. Most of the sequences unfolds in master shots (some in single takes), the camera relegating to showcase the confines of the abode, rarely embarking closer or growing more distant from the characters. Matuszynski and cinematographer Kacper Fertacz avoids a framing approach that pays grand tributes to the genius painter. Every frame brings the sense of watching a closer-to-reality family interaction. The intention is to draw us inside the isolated bubble. The well-crafted, interactive master shots, doesn’t for a single instance, divert our attention from the honest as well as cruel observations. There’s nothing here to distract ourselves. And, the distinct framing technique also allows us to choose on whose reaction we decide to focus. I particularly liked the long discussion between the three pivotal family members (in the exact middle of the film), shot in a VHS camera. I just can’t avert my eyes, although the relatable emotional truth, extracted from the scene was too hard to bear.

Veteran actor Andrzej Seweryn, who had worked with great film-makers like Alain Resnais, Andrzej Wajda, and Steven Spielberg, impeccably portrays the complex role of Zdzislaw Beksinski (won best actor trophy at Locarno Film Festival). He meticulously unfolds the intimate world of the controversial painter. Konieczna is incredible as the patient matriarch Zofia. She is the strong link holding the family, who sadly has no private place to vent her emotions. Konieczna doesn’t allow Zofia to be a mere shadow, soothing the agonies of the geniuses. She seems simple and fragile, yet there’s something strong about her composure. The Last Family may work lot better (and offer an more distressing movie experience) for those who had intimate knowledge of Beksinski’s works and the tragedies encountered by his family. Yet, for viewers like me, Mr. Matuszynski’s focus on the familial bond of the Beksinski’s, or the lack thereof, brings out certain universal emotions to deeply reflect on. The theme of unrealizable desires, virtual fantasies, and prolonged suffering enables to relate with our own silent reckoning about life. Although some of the behavior we witness in the narrative are too extreme, everyone’s family would have some factors that constituted the Beksinski family. Like Beksinskis, many of our families too was isolated from politics (or other external influences) and yet life (or at least our attitude towards it) didn’t change much even with acquisition of all the sophisticated material wealth.

The Last Family (123 minutes) is an unsettling portrait of the excruciating domestic life of respected and controversial Polish artist Zdzislaw Beksinski. Despite the deeply pessimistic themes and coolly detached observational style, the film ends up being strangely moving.

★★★★

Director Jan P. Matuszynski Interview — Tuck Magazine