Censorship has been a constant factor in Iranian cinema: either to curb criticism against the regime’s ideological stand or to banish what’s considered as ‘loose sense of morals’. Cultural and political context continues to impose limitations on the nation’s cinema. But the generations of genius Iranian film-makers never considered censorship as an impediment. They kept on carving new cinematic paths to interpret on their country’s rich cultural identity. The film form devised by the Iranian film-makers derived its influences from Persian poetry to Italian Neo-realist movement. The artistic insurgency had a lyrical visual language as well as a sharp focus to articulate the social context of oppression & impoverishment. The 1960’s was considered to be the new era in Iranian film-making. It was the decade Forugh Farrokhzad’s excellent short/documentary “The House is Black” (1963) and Ebrahim Golestan’s seminal film “The Brick and the Mirror” (1964) were made. Nevertheless, the inception of New Iranian Cinema (‘cinema motefavet’) was often associated with Dariush Mehrjui’s “Gaav” (aka The Cow, 1969). The Cow, which works both as a poignant human drama and subversive cinema, grabbed the attention of the West and inspired more film-makers to explore the contemporary social themes of Iran.

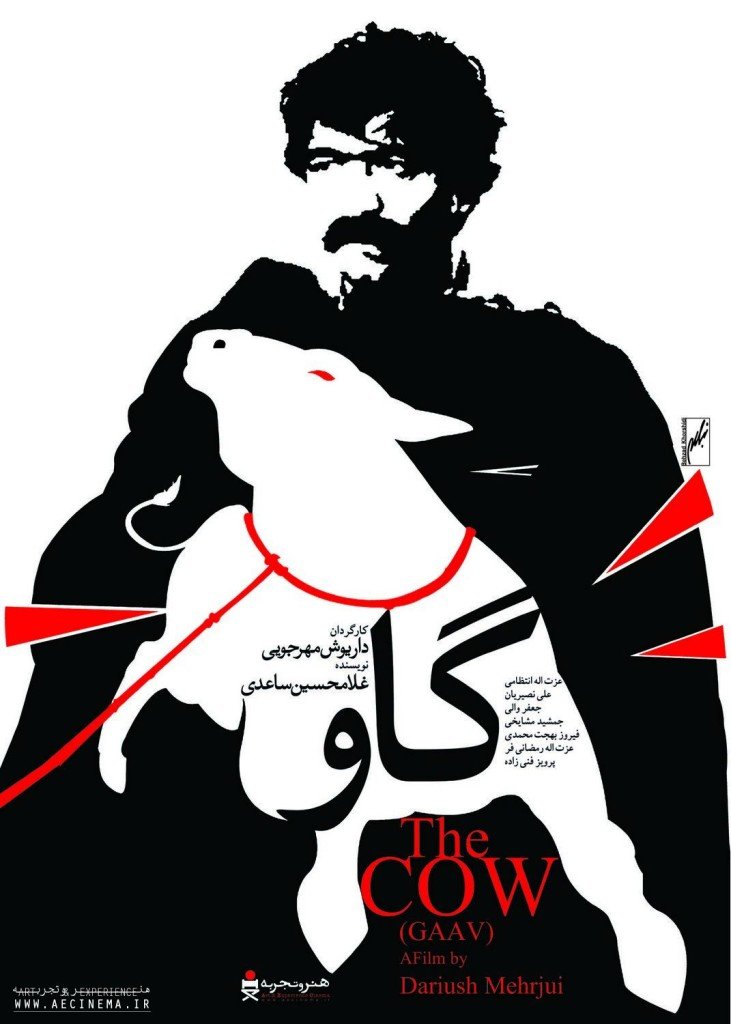

In 1968, the Iranian government established the Ministry of Arts and Culture to work out the censorship requirements (in the 1980s censorship practices controlled films prior to production). Although Mr. Merhrjui received funding from the Shah of Iran, the final product of the film was immediately banned for its ‘negative’ portrayal of rural Iran. Shah Pahlavi’s regime considered “Gaav’s” vision to be contradictory of their vision for modernization. The film was allowed for a domestic release only after the inclusion of a disclaimer, stating that the events portrayed in the film happened long before Shah’s regime. “Gaav” was smuggled out of Iran and won the critics prize (FIPRESCI) in 1971 Venice Film Festival (and also won a prize in the Berlin Film Festival).

In “The Cow”, writer/director Darius Mehrjui (UCLA philosophy graduate and film student) blends Italian neo-realism sensibilities and the sensibilities of an absurdist folktale. There’s an incredibly realistic portrayal of rural Iran’s socioeconomic situations and at the same time there are also some marvelous surrealistic, eerie touches. In the opening credits, we see two abstract figures – one human, other an animal – moving & blending together. This image, I think, conveys the central conceit of the tale. The narrative opens with the scene of roving children from a small village, accompanied by a grown-up bully, mercilessly harassing a mentally disabled guy. The sparsely populated village is visualized through the shots of passive spectators, a donkey cart, a dog, cluster of clay and stone houses, a mosque and a pond, around which all the lively activities in the village take place. A middle-aged character who keeps an eye on all the movements in the village through his window brings a light comedic touch. The faces of the village people (especially women & old people’s) seem to be burdened by the hard realities of poverty. Islam (Ali Nassirian) looks like the decision maker in the village. The chief and others looks up to him in the time of crisis. The only lively factors of the village are: Masht Hassan (Ezzatolah Entezami) and his cow.

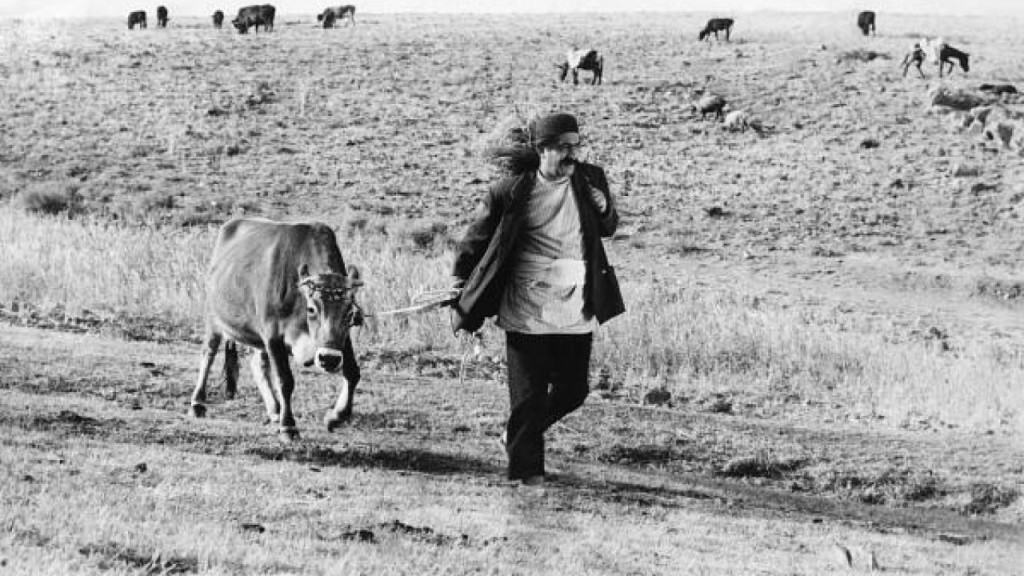

Hassan adores his pregnant cow like a child, taking her to graze in the open fields and washing her after a long day of work. The affection he has for the cow is more than the love he possesses for his wife (he just addresses her as ‘woman’). The ownership of the cow has also brought Hassan a distinct identity and social status in the village. The threat to this identity is signaled by a threat standing on the far horizon. When Hassan takes his cow outside for grazing, he sees three men from nearby village (called ‘Bolouris’) in a distant, small mountain range looking at his cow. He conveys this event to the villagers, who are all worried over the cattle-rustling group. Although Mr. Mehrjui conveys ominous feelings about the Boloruis in those initial shots, the real threat they present to the villagers is cloaked in ambiguity. Hassan sleeps in the cow shed, fearing a raid from the Bolouris. The next day Hassan goes to his work after confirming that the cow is safe. Later in the day, Hassan’s wife discovers the cow lying dead in the shed and her loud cries brings every person in the village. The villagers debate on how to convey this shocking news to beloved Hassan. Islam comes up with the suggestion to tell Hassan that his cow has wandered off and a fellow has gone after it. He also proposes to bury the cow in the old well. Islam and his villagers perceive how their plan had only made things much worse when Hassan gradually descends into insanity.

The screenplay of “The Cow” was co-written by popular Iranian writer Gholam Hossen Sa’edi. Sa’edi, who specialized in psychiatry, has said to have traveled with renowned Iranian thinkers like Jalal Al-e-Ahmad to Iran’s remote villages and wrote many ethnographic essays about his travels. Hamid Dabashi, the Iranian American professor, in his book ‘Masters & Masterpieces of Iranian cinema’ mentions the heavy influence of the Sa’edi’s short story collection “The Mourners of Bayal” in grounding the characters and realities of a village life. Mehrjui and Sa’edi’s script of “The Cow” offers a clear-eyed portrait of the dynamics in the village as well as they have imbued a Kafkaesque feel in Hassan’s transformation (in the later half). The first I watched this film I was wondering, ‘how to approach the film?’ or what’s the meaning of the events?’ “The Cow” isn’t devised as a representation of a single idea. It could be interpreted in different ways, complementing its subversive and metaphorical meaning of the images. Some critics call the film a parable about regimes often deceiving its people; some comprehend Hassan’s fate as the fate of rural Iranian people, deprived of identity and led astray by the government institutions; some see Hassan as the representation of Iranian cinema, prodded by bewildering censorship methods. The villagers’ fear for outside threat is positioned alongside their thieving and lying activities. When the cow dies they place blame upon ‘evil eye’ or on the outsiders. This process of blaming ‘outside’ parties (for all misfortune), while continuing to commit morally reprehensible acts could be interpreted on different levels. From a social perspective, the villagers’ conclusion about the ‘outside’ threat is similar to the government’s blame on every misstep on parties outside their nation’s borders. Whatever our choice of interpretation is, “The Cow” works primarily as a moving human drama.

Spoilers Ahead…………

Director Mehrjui’s rich aesthetic sensibilities and Sa’edi profound psychological exploration doesn’t underwhelm the emotional power we derive from Hassan’s personal experiences. By signifying the importance of the cow, from the both social and personal perspective, the film-maker is able to deliver the hard-hitting impact in the second-half. Nevertheless, the director doesn’t turn the narrative into a very dark territory. There’s a ‘Fellini-esque’ touch in how Merhrjui frames the baffled expressions of the villagers. Their reactions seen from distance allows for a small undercurrent of humor. He allows us to perceive the twisted nature of Hassan’s transformation (where he proclaims ‘I am Hassan’s cow’), without ever downplaying our emotional connection with Hassan. The distressing factor of the film is not just Hassan’s descent into madness; it lies in how the village community reacts to it. As they repeatedly find themselves in a situation unable to address (or find solution to) Hassan’s mental illness, the community slowly seem to give in to his illusion. As the man is stripped off his identity, the villagers overstep their boundaries to reach for some kind of resolution. At the end, the rebelling man/animal becomes a just a burden to be abolished. This disturbing notion is sharply expressed in the climax when Islam loses his senses to treat stubborn Hassan as an animal (‘get going you beast!’, he shouts). The movie’s success also belongs to the stupendous performance of Ezzatolah Entezami in the central character.

“The Cow” aka “Gaav” (100 minutes) is a seminal work of Iranian cinema which served as the precursor to the nation’s post-revolutionary cinema of Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Abbas Kiarostami, etc. The film could serve both as a touching cinematic experience and contemplated deeply from a philosophical point of view.

★★★★1/2

“Gaav” — Movies that make you think