William Wyler belongs to old school of Hollywood film-making where the script and casting and directing actors occupies a prominent place than auteurist flourishes. Wyler’s big dramas with big actors efficiently provided entertainment and valid social commentary. Directors like Wyler, Capra, and Billy Wilder won too many Academy Awards for direction, which might not have been often bestowed upon true American auteurs. Of course, we can’t possibly dismiss the consistently engaging works of these studio-backed directors as out-dated melodramas. The old school American film-makers’ depiction of emotional truth still has the power to resonate with contemporary viewers, and most of the themes they tackled remain socially relevant, or at least has an existential quality attached to it.

William Wyler’s directorial career can be neatly demarcated based on the works he did before and after World War II. Born in a small town (in 1902) near the Franco-German border, William Wyler gradually worked his way up to become assistant director in the Universal Studio productions. While the director is best known for blockbuster Christian epic Ben-Hur (1959), he actually worked as an assistant in Fred Niblo’s 1925 silent-movie version of Ben-Hur. After making studio-controlled and tightly scripted comedies in the 1930s under Universal, Wyler jumped to Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Here he made some of his most memorable earlier films (The Letter, The Little Foxes, etc), collaborating with the great star-actress Bette Davis and much sought-out cinematographer Gregg Toland (Citizen Kane). Before deciding to contribute to the American war efforts, Wyler made the heightened melodrama, Mrs. Miniver (1942, Wyler won his first Academy Award for the movie).

The brutal war-time experiences enabled Wyler to get much closer to the emotional truths and agonies of his on-screen characters. During the war, he flew in combat-ready B-17s, shooting footage for his impressive documentary The Memphis Belle. During the bombing raids (in B-25s), an incident caused him permanent hearing problem. Wyler also made another honest genuine war documentary titled Thunderbolt. After returning to civilian life, he seemed to be the perfect candidate for directing MacKinlay Kantor’s novella ‘Glory for Me’. In 1944, producer Samuel Goldwyn’s wife Frances showed Mr. Goldwyn an article in Times about traumatized war veterans (the term ‘PTSD’ wasn’t commonly used then). Goldwyn hired former wartime correspondent MacKinlay Kantor to write the story. Scriptwriter Robert E Sherwood (The Petrified Forest, Rebecca) later developed the script under the title The Best Years of Our Lives, and the directing job naturally fell on to Wyler who was under contract with Goldwyn Productions. In 1947, The Best Years of Our Lives won 7 Oscars (including Best Director and Best Film) and happened to be highest-grossing film since David O Selznick’s Gone with the Wind (1939). Today, the film might sound like one of those familiar melodramas, put forth to confirm the popular perception of American nationalism. But such assumptions would only be too wrong. William Wyler had worked hard to strip the essentials of the narrative to its basic, making its themes and characters universal in nature. In his review, the late Roger Ebert praised the film in this manner: “As long as we have wars and returning veterans, some of them wounded, ‘The Best Years of Our Lives’ will not be dated.”

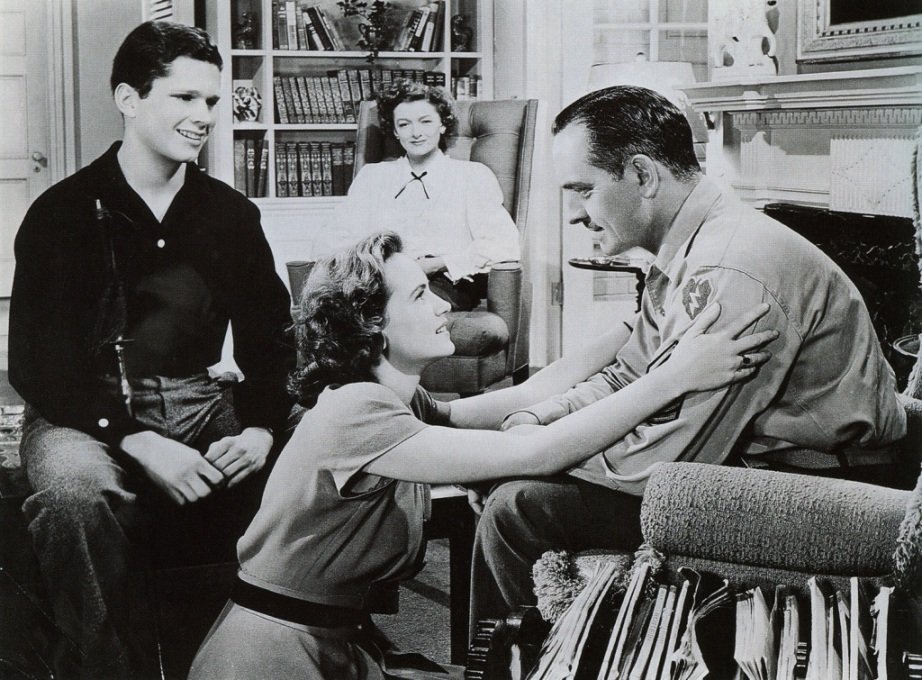

The Best Years of Our Lives tells the story of three returning war veterans – Air Force Major Fred Derry (Dana Andrews), Navy man Homer Parrish (Harold Russell) and Army Sergeant Al Stephenson (Frederic March) – who get acquainted with each other as they fly on the same aircraft for nearly a day to reach their hometown ‘Boone City’ (a fictional town modeled after Cincinnati, Ohio). In the taxi, journeying towards home, each of the three individuals become increasingly quieter as their respective neighborhood looms over. The vestiges of the brutal war are caged inside their souls and they wonder how it will affect their lives and their loved ones. Homer has entered into the war immediately after graduating from school and he has lost both of his hands. He has been adeptly trained to use the prosthetic hooks, yet he is quite sure that his working class parents and sweetheart Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell) won’t look at him the same way before the war. While Homer’s emotional pain is plainly visible when others treat him as an object of pity, the existential quandary of the other two are buried much deeper.

Fred Derry gets off at impoverished quarters of the town and immediately finds out from dad that his wife Marie (Virginia Mayo) – Fred married her few weeks before the war – is working in a nightclub and moved to a better furnished apartment. Marie is a partying girl who hopes their life will ever be the same and forces Derry to wear his Air Force Uniform to show off to her friends. She easily dismisses his trauma and expects him to earn enough money to fuel her routine party schedules. Fred naturally refuses to meet her demands and truly he doesn’t possess the job prospects to do so. He has previously worked behind a soda fountain in a small drug store which was now transformed into a big supermarket. The manager reluctantly gives him the frustrating job of assistant floor manager. The only sweet thing that has happened to Fred after his return home is meeting with radiantly beautiful Peggy (Teresa Wright). Peggy, the only ray of light in Fred’s life, is former Army Sergeant Al Stephenson’s daughter. Al returns home to his empathetic wife Milly (Myrna Loy). Yet, picking up where they left off seems to be difficult job. There’s natural discomfort in the husband-wife relationship. Al returns back to his banking job and offered a cushier job title. To capitalize on Al’s time in the service, the bank President puts him in charge of passing loans for war veterans. Al is torn between his responsibility to the bank and his basic humanity to lend hand for the struggling fellow servicemen. He passes his days with a drink on his hand.

The Best Years of Our Lives was then known for Wyler’s revolutionary attempts made within a studio-backed picture. Wyler’s casting of non-professional Harold Russell is said to predate Roberto Rossellini’s use of non-professional performers in Open City. Harold’s casting was considered as the perfect example of ‘art imitating life’. The film’s original script was rewritten to accommodate Harold, who lost his hands in an accident during World War II. By casting a real-amputee and non-professional actor in the role of Homer Parrish, Wyler set new benchmarks for his time. Homer’s on-screen anguish as other stare at his prosthetic hooks wasn’t just a simple act. It was an achingly real emotion for Harold. Wyler closely worked with combat veterans during the film’s pre-production. He came across a training film called ‘Diary of a Sergeant’, where it’s shown how Harold efficiently trained himself to use the prosthetic. After witnessing Harold’s natural depth of feeling in the videos, Wyler was sure he’d found Homer. Harold initially rejected the role. When he took on the character, it is said that Harold did his best to avoid any awkwardness with his fellow actors. Mr. Goldwyn tried to send Harold for acting lessons, but Wyler condemned it, preferring Harold’s raw performance. Wyler’s strong decision makes Homer to be one of the most memorable characters in movie history. Harold’s non-acting clumsiness and introverted nature provides emotional depth to the character, especially in the era before rise of exemplary method-actors. The academy voters gave Harold an honorary gold statuette since they were unsure about his Oscar chances. However, Harold walked home with the Oscar for supporting actor. Hence, he happens to be the only actor to receive two Oscars for the same part. Homer Parrish was Harold’s only cinema role and he later continued his work as an advocate for the differently-abled.

The positive aspect of scriptwriter Sherwood’s rich realization of the characters is his less use of cinematic constructs. The three individuals feel much like product of the society rather than cardboard figures built upon melodramatic base. Apart from Fred and Peggy’s romantic struggles, the script doesn’t invent any inorganic developments on the narrative course. Whatever conflicts plaguing the three war veterans returning back home, it’s already there in place before the narrative starts. How they gradually become part of this conflicted yet ‘normal’ life, without succumbing to the darker notions makes up the plot trajectory. Sherwood and Wyler instill a sense of optimism and minor accomplishment in the ending. Nevertheless, there’s also sharp indication that the struggles will continue, particularly evident in Derry’s final dialogue to Peggy: “You know how it’ll be, Peggy. It may take us years to get anywhere. We’ll have no work, no decent place to live. We’ll get kicked around.” The rebirth of self and rejuvenation of the society is shown to have been realized, but we are left unsure about the trials to come.

Renowned cinematographer Gregg Toland’s remarkable use of deep focus is one of the important talking points of the film’s visual language. Wyler and Toland’s command over form is visible right from the early sequence when Homer wakes up in the plane to witness the calm sun-lit sky. Except for the sweeping shot of decommissioned military air crafts, Wyler keeps the camera movements restrained and minimal (I read that in order to construct realistic environment more attention was given to production design and Wyler even advised his actors to buy their clothes from local shops). The scene featuring junkyard of air-crafts was a formally and thematically powerful one. Sitting inside the comfort of a broken-down aircraft and looking through its glazed window, Fred Derry simultaneously relives the glory of his recent past as well as forces himself to get it out of his memory. Wyler cuts between long-shots and mid-shots, focusing on Fred’s face, presenting us the worn-out shell of the airplane and Fred. Both the machine and the man are stripped off the qualities that made them essential during the war (isn’t it, in the modern battle arena morality is obscured to turn humans into killing machines). The machine’s part could be easily disposed for other purposes, but what about the man’s soul? Could a man’s soul as easily as a machine transform itself to serve an entirely different purpose? It’s a timeless question for people navigating through their societies after fighting a bloody war. The capitalist economy in the seven decades after the release of Wyler’s movie has gained notorious reputation, yet what has remained unchanged is the sense of anxiety and dread faced by war veterans, returning to increasingly short-sighted, intolerant society.

The Best Years of Our Lives (170 minutes) is an enthralling classic which sharply blends social commentary with engaging storytelling method. It is emotionally powerful without being overly melodramatic and hopeful without being naive.