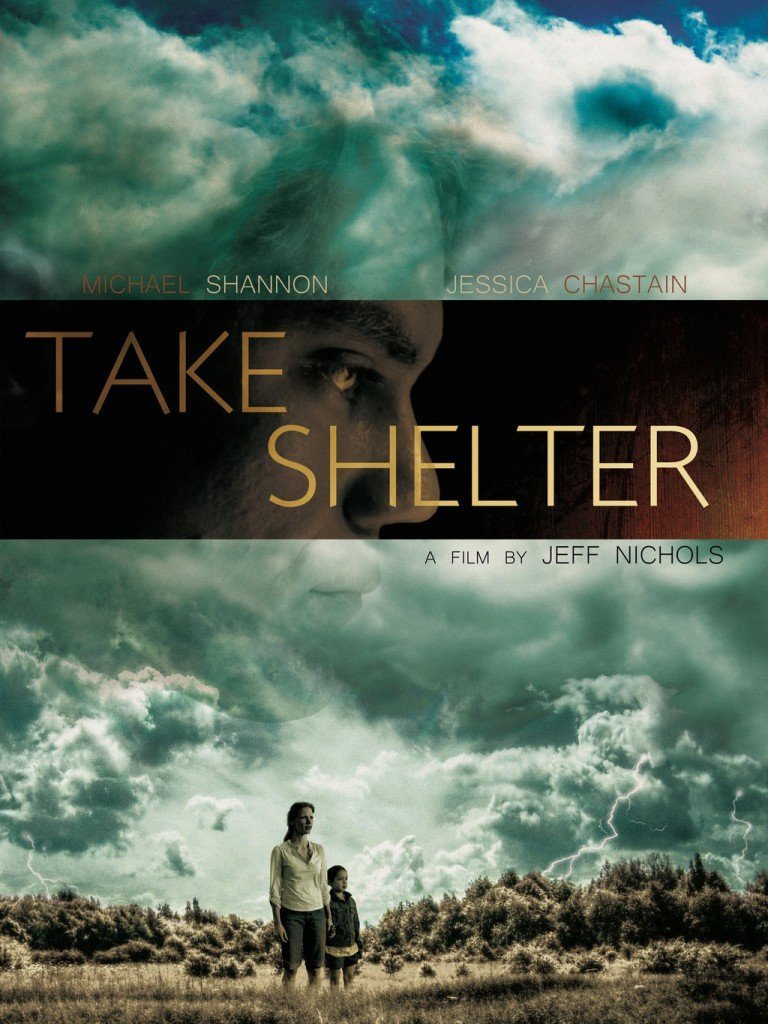

Few years back, a storm brooded over the American economy, sending tornadoes of dread to the average American families. The ensued job losses ravaged the modest comforts enjoyed by the families of blue-collar workers. Even after the financial recovery, an anxiety over losing life’s simple comforts pervades on the mind of a common, working man. A storm broods in Jeff Nichols’ intense drama “Take Shelter” (2011) too. It is both literal as well as figurative. The protagonist does manual labor for a sand-mining firm and has the usual externalized worries over mortgages, health insurance, etc. But, what separates him from the aforementioned average American is that his fear and anxieties are also internalized. Curtis LaForche, the protagonist, has visions of literal storms, capable of bringing total destruction. So he decides to build an elaborate storm shelter in the field, before his house. It is the kind of decision where the externalized economical anxieties clashes with internalized emotional storm, shadowing the possibilities of hope and familial love.

“Take Shelter” would immediately bring to our mind the tale of Noah and may insinuate that it is a tale of prophecy and faith. But, Jeff Nichols’ never latches on to religious symbolism for this tale of alleged apocalypse. He rather designs Curtis’ mental deterioration as a nuanced exploration of dread and anxiety. By nuanced, what I meant to enunciate is the manner with which director Nichols depicts Curtis’ emotional anguish. The character is very much grounded, imbued with little relatable details of everyday workers’ world that we get a clear idea of what Curtis might lose if he gives into his nightmares. The overwhelming sense of fear and horror pervades in the movie’s atmosphere are also brilliantly brought out through small naturalistic details (like the vast open skies resembling the gaping mouth of a beast).

“Take Shelter” opens with a subjective shot of Curtis standing alone and facing the storm that brings rain with the viscousness of motor oil. It is one of his dreams about the uncanny monster of a storm, which looks all the more foreboding because of the familiar landscape. Curtis lives in rural Ohio with his loving wife Samantha (Jessica Chastain) and they serve as attentive parents to their six year old deaf daughter Hannah (Tova Stewart). Curtis has a good paying job to take care of Hannah’s cochlear implants and they are saving up enough money to take a trip to Myrtle Beach. But, the intensity of Curtis’ dreams increases as in one episode, the dog rips him into pieces. He wakes up to feel the pain of dog’s bite in the dream. Later, Curtis builds a little shelter for the dog and keeps it away from the family. Gradually, each nightmare envisions more baleful situations for his family. When he is wide awake at work, he sees locusts blotting out the sunlight and hears thunder crashes, while the sky stays blue and bright.

Curtis, the gentle soul, knows that all this impending sense of doom is only in his head. He could also grasp the reason for these schizophrenic delusions. In her early 30s, Curtis’ mother (Kathy Baker) suffered from similar kind of delusions, and still lives in an assisted-living facility. He thinks there might be some genetic claims to his predicament and seeks the help of local doctor. Curtis’ best friend and co-worker Dewart (Shea Wingham), who doesn’t know about his friends’ visions, enviously declares “You got a good life”. At a later time, when Curtis’ normalcy and achievement of the American dream wavers, Dewart also warns him “I don’t want you to fuck up”. But the danger of being annihilated by an external force looks so real for Curtis (and for us too) that he starts to obsessively put his mind to the storm shelter. Is he going to face the ‘storm’ or burrow himself deep inside a ‘shelter’? (or a proverbial grave). Obviously, the question makes sense when seen from both figurative & literal sense.

Director Nichols and cinematographer Adam Stone evokes the sense of dread and the feeling of being caught inside Curtis’ head by using attuned visuals of the rural flatland setting. The funnel-shaped clouds, big industrial shovels digging at earth, spider-webs like lightning are on the outset, just simple images, but these collectively and gradually create vague, brooding sense of cataclysm. Although Curtis’ activities could be easily made to only read as personalized or internalized apocalypse, Nichols chooses to effectively construct the dreams to put ourselves in the middle ground of uncertainty and certainty (as experienced by Curtis). The director also doesn’t rely on changes in hues to signal us of the visions, which again is to keep us in the unsure state. Nichols’ debut feature “Shotgun Stories” and his 2012 uncanny coming of age drama “Mud” were concerned with family legacies and absentee parent. In “Take Shelter”, Nichols’ knack for detailing familial communications (for example, the beautiful conversation, when Sam and Curtis stand in the doorway of Hannah’s bedroom to watch her sleep) is so compassionately etched that we cringe at Curtis’ unstoppable absurd actions. Director Nichols also uses his pet themes to create nuanced as well as different moods. His critically acclaimed recent film “Midnight Special” looks like a restrained, ambiguous sci-fi, but at its core it’s another profound exploration of parent-child relationship.

The script does tick along slowly and clumsily at times. Some of the plot points are very obvious. For example, when we see Sam showing sense of relief after hearing about insurance benefits, attached with her husbands’ job, we could immediately judge what’s going to happen few scenes later. Despite the unsubtle plot points, Nichols show good eye in heightening or restraining an actors’ performances. Even actors like Ray McKinnon (as Curtis’ elder brother), Shea Wingham seem to create a strong impact with their smaller roles. Chastain’s entirely reactive, vivid performance lends the sense of hope, counteracting Shannon’s darkness (I read in the IMDb trivia page that Jessica Chastain was only paid $100 per day for the role of Samantha). She elegantly actualizes the emotions of love and fear, while witnessing her husband’s mania. The kid Stewart is another earnest presence in the narrative. The film’s major strength next to Nichols’ direction lies in Michael Shannon’s portrayal of gentle Curtis. Prior to “Take Shelter” Shannon played a psychologically unhinged character in Mendes’ “Revolutionary Road” and as a wild-eyed schizophrenic in Friedkin’s “Bug”. So, Shannon playing Curtis could have easily brought out a sense of deja vu. Nevertheless, his ability to make us understand the characters’ embarrassment and agony imparts sadness, compared to the unnerving feeling inherent in those previous characters. His public outburst do instill fear – the one that of seeing a gentle soul being destroyed by a doomed fate.

Any discussion of “Take Shelter” wouldn’t feel full without talking about its ending. What does it confirm? What does it mean? Is it ambiguous or literal? The objective lensing of the final frame does make the ending vision literal, and if it’s literal it could serve as last-minute hollow twist. On the outset, this ending does seem absent of ambiguity (due to objective viewpoint of Sam & Hannah), but I felt that the family facing a forthcoming storm could be interpreted in a metaphorical level too. Despite what the visuals are indicating, there is hope in it, because Curtis isn’t now confronting that emotional as well as literal vortex alone. Yeah, in our lives all kinds of storms rumble over the horizon, and the only thing that matters in the end is standing together as a unified family to confront those naturalistic or man-made demons.

“Take Shelter” (121 minutes) is a nuanced character study of a respectable man, taking refuge in an insane, self-fulfilling prophecy. Its occasional narrative flabbiness is overcome with assured direction and riveting performances.