Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece, Bicycle Thieves (1948) opens in front of a freshly reconstructed government building with a crowd of city’s skilled yet unemployed laborers. The story’s central character after getting a job of hanging up posters, promising he would turn up with his pawned bicycle, walks back to home and comes across his water bucket-carrying wife, the camera all the while getting us acquainted with the wider vista of post-war ravages and poverty. There’s only diegetic sound and no other stylistic adornments. De Sica’s Shoeshine (Sciuscia aka Ragazzi, 1946), however, opens in an contrasting manner.

We see two boys on horseback in the countryside, consumed by the thrill of speedily riding their favorite horse. Although De Sica’s tone here conveys happiness, it sort of resembles his staging of the fevered dream imagery in his previous melodrama, The Children Are Watching Us (1944). But soon De Sica informs us that the boys’ dreams of riding a horse into a glorious future are still just a dream.

They are shoeshine boys named Pasquale Maggi (Franco Interlenghi) and Giuseppe Filippucci (Rinaldo Smordoni), their place in the social ladder clearly exemplified by the shot of them shining shoes of obscure, nonchalant American GIs. Nevertheless, the boys are supposedly closer in achieving their dream of owning the horse named ‘Bersagliere’ – title of Italian infantry division. Few weeks of shoe shining would provide them enough lire to gallop around. But the boys get a chance to earn the remaining money in one go. Giuseppe’s older brother, Attilio offers the boys the job of selling two blankets stolen off the Americans to an old fortune-telling woman. The boys take the job without understanding the bigger con planned by the brother and his gang.

Pasquale and Giuseppe, nevertheless, receive their end of share and they buy ‘Bersagliere’. In one of the film’s beautiful shots, we catch the boys riding the horse around the city amidst the other hooting shoeshine boys. The rest of the narrative showcases how the boys’ dream is clamped down by the institution, brimming with adults plagued by fascist tendencies. Pasquale, the older of the two, is an orphan and sleeps in the lift of an apartment building. After earning enough cash to buy the horse, he sleeps in a bed of hay, in the stable. Giuseppe has a family, but they are poor and struggling. He is the cutest kid of the two, a characteristic that allows him to get a chocolate or two from American soldiers which he gifts to his little girlfriend (Anna Pedoni).

Related to Shoeshine: Cairo Station [1958] — The Struggles against Sexual Repression and Social Oppression

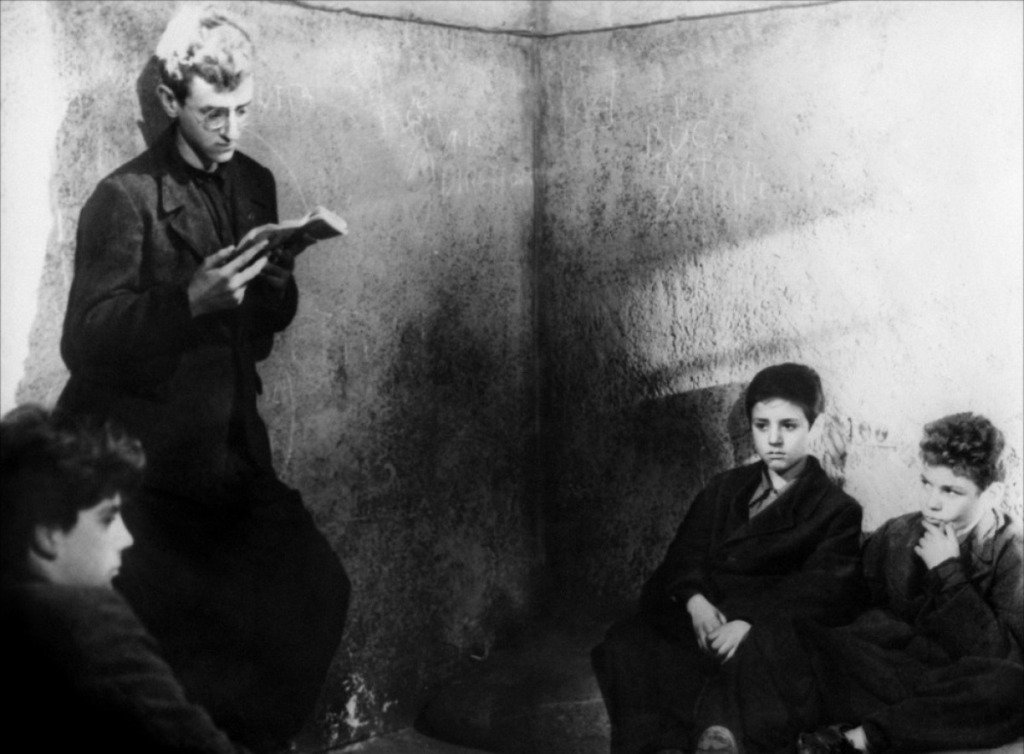

When the police get hold of Pasquale and Giuseppe, they strictly adhere to the adult code of not ratting out on their ‘friends’. The boys are sent to juvenile detention center until their case comes to hearing at court. Adding to their woes, Pasquale and Giuseppe are separated and confined to different, overcrowded cells. Giuseppe reluctantly ends up under the charge of Arcangeli (Bruno Ortenzi), a hardened teenage delinquent, rumored to have robbed a bank. Moreover, the boys’ friendship is truly tested when the stern prison head, Staffera (Emilio Cigoli) plays a cruel trick on Pasquale in an attempt to extract the names of conmen the boys are fiercely protecting so far. The rift caused by this incident only widens, thanks to adults’ manipulations and sets off a fatalistic trajectory.

Shoeshine’s script was initially drafted by De Sica’s frequent collaborator Cesare Zavattini, based on the director’s own ideas. Later, a team of script writers were brought in to fine-tune the narrative, prominent among them is Sergio Amidei (who closely collaborated with Roberto Rossellini in Rome, Open City [1945]). Unlike Rossellini’s picture or De Sica’s very own Bicycle Thieves, the neorealist formula in Shoeshine mostly drives the story, not much the film’s stylistic choices. Shoeshine was shot within the studio, had minimal footage of street life, and brims with expressionist cinematography (the suggestive use of dark and light). Nevertheless, De Sica’s supreme ability to work with non-professional actors, particularly children, is evident in this film, where he acutely observes a community of boys forced to mature before their time. The movie is also less melodramatic compared to De Sica’s previous works, allowing him the space to present the narrative without unnecessary embellishments.

Although the narrative is progressively bleak, De Sica infuses right amount of humor and sentimentality, emphasizing on his humanist commitments. Despite setting the characters within a fatalistic narrative, the character themselves are distinct and believable enough. Giuseppe’s conflict over turning against Pasquale (in spite of the latter’s supposed betrayal) is as much believable as Pasquale succumbing to the warden’s pressure. In fact, the brokenness of impoverished boyhood is one of the prominently reflected themes in neorealist films, which was later examined in a more introspective and subtle manner by French New Wave figures (for e.g., Truffaut’s 400 Blows).

Also Read: The Cow [1969] — A Pioneering Masterpiece of Iranian Cinema

Zavattini and De Sica clearly underline how the beauty and power of childhood (witnessed in the film’s opening sequences) gets corrupted by an authoritarian adult world. The narrative set up gradually examines how the iron-clad prison system methodically disintegrates the trust the boys had for each other. The decaying of trust comes full circle as the one boy beats up the other in front of the very object of their dreams. After the inevitably grim outcome, the eternal silence of one boy pitted against the wailing of the other the ‘dream’ gallops and flees like a soul separated from the body.

Shoeshine, like most of the neorealist classics, was badly received in Italy during its release. Neapolitans precisely wanted to escape the kind of reality that was sharply portrayed on-screen. However, it enjoyed great success overseas (especially in US and France), and went on to win the honorary Oscar. Overall, Shoeshine (87 minutes) is one of the very influential neorealist movies that painted a vivid picture of post-war Italy’s social problems through the tragic destinies of two impoverished, criminalized boys.