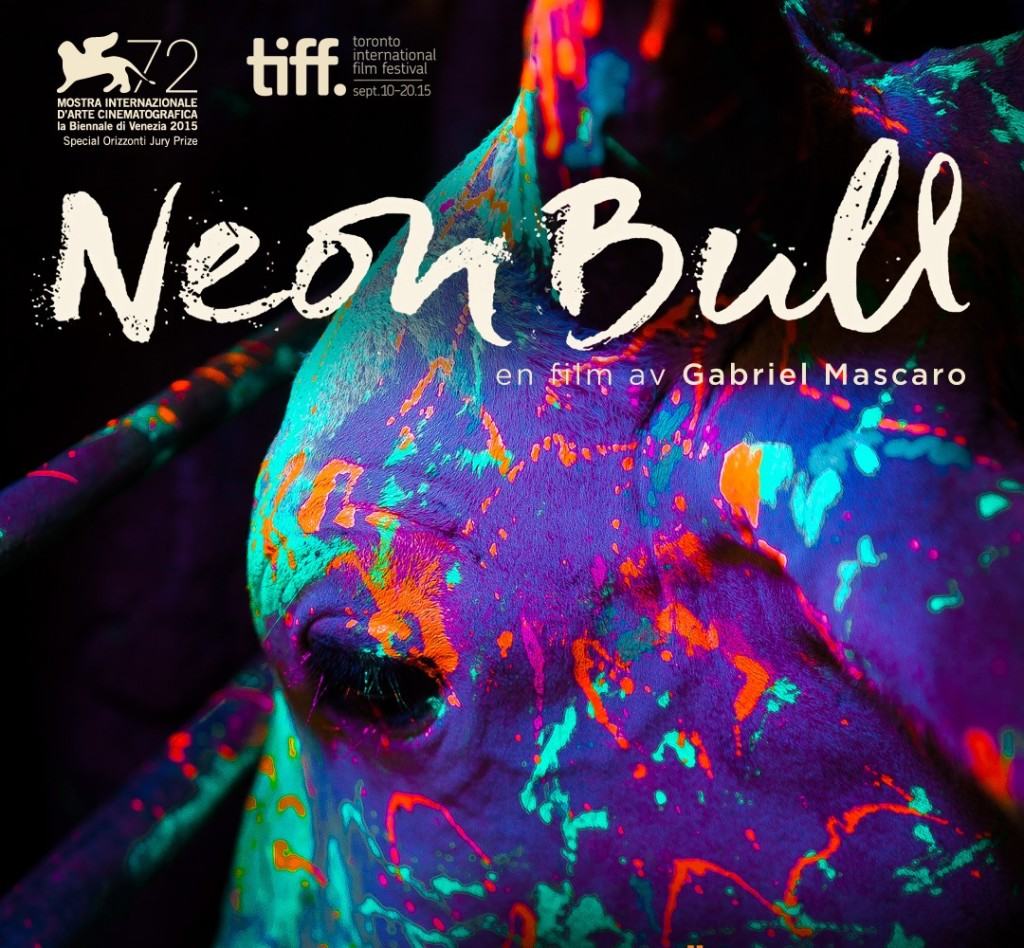

Neon Bull earned a Special Mention at last year’s TIFF’s inaugural Platform competition and won the Special Jury Prize in Venice’s Orizzonti section

Except for the word ‘Neon’ in the title, there’s not much connection between Nicolas Winding Refn and Brazilian visual artist/film-maker Gabriel Mascaro’s films. May be I could make some far-fetched connection: while Refn’s film explores the narcissism in fashion world through its aspiring teen protagonist, Mascaro’s “Neon Bull” (‘Boi Neon’, 2015) effortlessly studies the aspirations of its physically toughened protagonist to be a fashion designer, who occupies the lower rungs of socioeconomic ladder. Of the many aesthetic and thematic contrasts that exists between the films, there’s a vital contrast in the way I related or experienced these films: as the ‘Demon’ perpetually pulls out life from its characters, making them as beautifully bland as mannequins, the ‘Bull’ infuses life into its characters, whom at first seem like shoddy rural people involved in exploiting bulls to make a living. Now, enough of me, trying to tediously equate the relations between the two strikingly different works. “Neon Bull” is the kind of film that kind of makes you cautious to not show your prowess in vocabulary to concoct superlative adjectives because there is no hint of grand-standing in the conception of each scene. It is also hard to write about a movie like “Neon Bull” since the social context or issues dealt with are diffused within the extraordinarily crafted painterly visuals. To those uninitiated, the unassuming, languid pace of the film might push them to a conclusion that nothing is said or happens. But, if you possess little concentration and patience this vigilantly documented piece of cinema would subtly pass on its notions & complicated meanings. You would then start reflecting or even relating with the strangely sensuous story of bull handlers in the remote corner of Northeast Brazil.

What’s it about? “Neon Bull” is about the unceasing tensions that exist between countryside and the rapidly developing towns or between bodily desire and emotions. It is the story about a hulking rodeo guy, exhibiting his artistic streak in designing alluring outfits. A tough-looking dreamer with an unwavering and deep understanding of human emotions and as he moves through the embellished landscape, he looks like a brave, humble artist floating through the contrasting urban/rural shadows, while also consistently transcending his constrained space. I am sorry. That last sentence came out from the word-monger within me, trying to prove my worth as ‘movie analyst’. The film does the opposite: it doesn’t thrust anything upon us or prove something. “Neon Bull” opens with a very slow lateral pan across the wide-screen to show corral fencing, within which a bull lazily sits atop another bull. Iremar (Juliano Cazarre) is the cowboy, who wrangle bulls in and out of the pen. The bulls and Iremar are part of traveling Vaquejada (rodeo), scuttling around the impoverished Northeast area of Brazil. In the rodeo sport, bulls enter into ring, where two riders atop exotic horses, attempt to bring it down, by ripping off the bulls’ tail tussles. Upon hearing about this traditional sport or about Iremar, we now withheld a judgment, but the beauty of Gabriel Mascaro’s elegant visuals is in the way it never passes judgment on the characters or in their activities. They freely roam around the parched landscape and are always viewed from a distance, but gradually we seem to form a strange connection with them.

As the saying goes ‘don’t judge a book by its cover’, Iremar might be a roughneck, but he has talent to delicately design women’s clothing and bikinis. The other members of his traveling rodeo are: Galega (Maeve Jinkings) with whom he alternately bonds and fights: Galega’s little daughter Caca (Alyne Santana); the fat Ze (Carlos Pessoa) and Mario. Galega is a single mom (the whereabouts of her husband are unknown) who is frustrated with Caca traveling alongside her, refusing to stay with granny for education. Caca is a precocious kid, who desperately desires for a father figure (and nearly finds one in Iremar). The desire to get a good sewing machine for feeding off his talent makes Iremar and simple-minded Ze to steal on the nearby horse auction camp, where rich men buy exotic-looking horses. The thing they are after would initially make you squirm. Ze rubs a cloth on the backside of a mare in heat and later holds it near the face of a male horse. Iremar masturbates the horse to catch the horse’ semen in a bottle (the purpose is not said). But this scene is staged in a perfunctory way rather than to merely shock. It is not staged in an exploitative and grossly humorous manner. This episode indirectly leads to the arrival of attractive young man with a ponytail named Junior (Vinicius de Oliveira), who brings out hint of jealousy from Iremar (he disrupts the early family-like dynamics). If there is a deliberately designed event in this muted narrative, it is the chance meeting between pregnant perfume saleswoman Geise (Samya de Lavor) and Iremar.

“Neon Bull” boasts vignette kind of film-making, which by being meandering and lyrical actually deepens our understanding of the characters or their socioeconomic afflictions. In cinema, the predominant rule is that to get intimate with characters and their emotions, one need to get closer to the performer. Director/writer Gabriel Mascaro does the opposite to yield the same result. There’s not a single close-up and by stepping back, he allows the characters the much-needed space to calmly show us who they are. Except for the precise lateral pans, we don’t see much of the camera movements, which mean that nothing is shoved into our face. Minute by minute, we just observe the replicated life details of impoverished humans who face dearth of professional opportunities. By doing so, the existential trappings and bodily desires of Iremar or Galega resonate with us. It is a movie of small moments and small gestures, but it slowly rolls around to pass upon a remarkably arresting movie experience. Mascaro’s intention is not to tell a story or construct a character arc and so the dialogues are not expository. There’s no narrative meaning in the words uttered, as the intention of dialogues here is to only showcase the reality of these characters’ lives.

Does the pulling of the tail tussles of frightened bulls by the horse riders insinuates an allegorical statement on the socioeconomic spectrum in Brazil? By showing the rapidly industrializing country landscape, does Mascaro lamenting for the Northeast? Is there a profound meaning in the way Iremar uses the ripped-apart tail tussles to use it for his fashion designs? And what does the final image of Iremar and Galega continuing their mundane works say? Does it say that these freely roaming around characters can’t escape their impoverished fate? Again, I got to stress on that “Neon Bull” is not the easily categorizable movie, which raises questions and pushes you to find answers (or come to your own conclusion) through repeated viewings. The pleasure and pain of this film could be fully experienced by not ruminating on what the film could be about. In the interview to filmcomment.com, director Mascaro says his film is “a discussion of the body in the cinema, ad how to look at body in the cinema……..a struggle of space, a body that struggles for space, that is asking for space”.

On one hand, you have the movement of bodies in a cyclic manner through the journey on road; there is practical, professional treatment of bull & horse bodies; then, on the other hand you have body movements and activities that crave for pleasure and sex. The reason why the ‘horse semen extracting’ scene comes off less shocking is because Iremar behaves in the casual manner he usually treats the animals. There’s an instance where group of nude men showering (once again the nudity is viewed in a distant manner). In another instance, Galega waxes her pubic hair. Her thigh placed on the trucks dashboard obscures he genitalia. The intention in these scenes is not to extract titillation (the camera never lingers on the body), but just to perceive a muted sensuality within the quotidian events. Eventually, the necessary emotional catharsis is provided for the characters through sex: Galega with Junior; and Iremar with Geise. Much of the subtle humor in “Neon Bull” is related to a sense of irony. In both the sex scenes, you could see the characters not able to experience pleasure by escaping away from the places of work.

Galega stands inside the dark, bull pen as Junior pleasures her, while the other sex scene unfurls on the cutting table of clothing factory (there’s another irony here: bodies are lying naked on a table where clothes flow in abundance). And the sex scene is not the sex you use usually witness in cinematic (it is the kind which provoke people to walk out). The six or seven minute uncut love-making just looks like a surreal moment (like the previous bizarre burlesque dance in the barnyard), where the two characters are in a state of suspension, floating far away from their mundane lives. And, look at the interesting way Mascaro cuts this scene: exhausted Iremar rolls around (with Geise above him), just like the bull in the arena that tries to get up after pulled down by the horses. A body that desired unbridled intimacy, now ‘struggling for space’. By the very final shot, we know a transformation has happened within the characters’ identities, even though they all seem to inhabit the same space. May be this unaccountable, nuanced transformation is an allegory for the silent transformation of Brazilian body-politic (In an interview, Mascaro stated “I have a special interest in body politics, or the bio-political, so I want to take physical love and affection and the effect of work on the body and place these things side by side.”)

Obvious parallels could be drawn in the treatment of mares and bulls. It perfectly works as an allegory for the gender identities. But, Mascaro is mostly interested in traits of the characters and not in stressing on those metaphors or allegories. A simple porn magazine is used to tell the desires and limitations of three different characters. However, what Mascaro leaves out is character idealization. He is not showing Iremar and his gang as victimized souls of Brazilian economy or as noble, pure souls with no money. Everyone has their flaws, does what they perceive to be normal, and knows that life goes on. Still the necessary compassion or some sort of emotional connection is achieved through the distinct film form. Mascaro and cinematographer Diego Garcia (who later went on to film Apichatpong Weerasethakaul’s “Cemetory of Splendor”) initially concocts the camera movements in the most mechanical manner, but gradually a fluidity is attained and we get a sense of life flowing through the frames. It’s pretty much a documentary-like approach, which infuses warmth and human touch as the camera keeps on moving subtly. Another commendable aspect of Mascaro-Garcia duo is how they have connected a thematic link through seemingly episodic images. Let it be the long, tracking shots of confused body movements of the bulls or the monochromatic red palette in the surreal trans-species dance or in the sex scene on factory floor, it all plays along the predominant theme of exploring space and intimacy between different bodies. So, it’s not just a pseudo-art-house feature with meaningless formal flexing of visuals.

Thirty-two year old Brazilian director Gabriel Mascaro, with his second feature-film “Neon Bull” (101 minutes) shows marvelous control of his material, whose tenderly humane and matter-of-fact erotic themes could have easily devolved into exploitative territory. Along with Carlos Reygadas, Kleber Mendonca Filho, and Ciro Guerra, Mascaro comes across as yet another talented, contemporary Latin American film-maker to watch out for.