Memory is not like a well that you dip into or a filing cabinet. When you remember something, you remember the memory. You remember the last time you remembered it, not the source. So it’s always getting fuzzier, like a photocopy of a photocopy……even a very strong memory can be unreliable because it’s always in the process of dissolving.

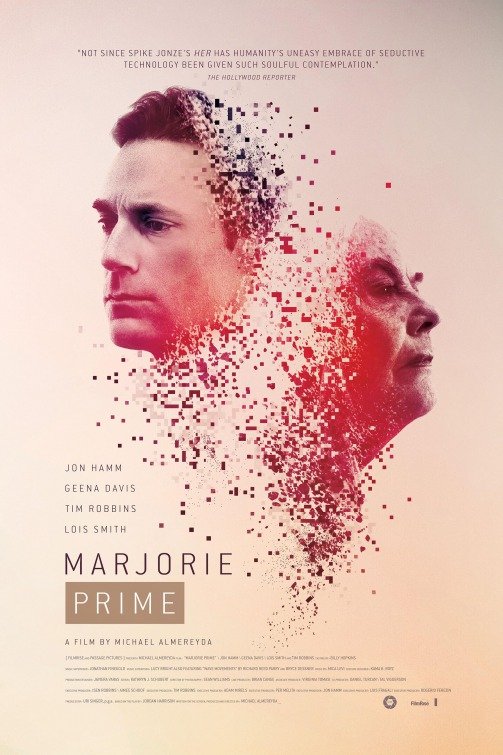

American film-maker Michael Almeredya’s films were always interested in observing the human condition, musing on the malleable memory and our relationship with ever-changing technology. Of course, Mr. Almeredya’s vision isn’t as ambitious or accomplished as that of great film-makers like Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Ingmar Bergman, and Andrei Tarkovsky whose unique craft delved deeply into these subjects. Yet Almeredya’s minimalist, modestly-scaled films are definitely thought-provoking and oft boast a fine emotional core to match its intellectual trappings. The director’s recent film Experimenter (2015) chronicled the controversial social experiment of social psychologist Stanley Milgram which raised disturbing questions about the plasticity of human nature, free will, etc. Now with the self-contained, low-key chamber drama Marjorie Prime (2017), Almeredya poignantly explores the elusive, slippery thing that defines our existence: memory. Both Experimenter and Marjorie Prime could work as the perfect double bills to reflect on the vagaries of human nature [Almeredya’s exciting upcoming projects includes a biopic about Nikola Tesla and an adaptation of Don DeLilo’s White Noise] .

Marjorie Prime was based on Jordan Harrison’s Pulitzer Prize nominated play which is set in the near-future, probably in the 2040s or 2050s. Being a stage-play, the film is less interested in imagining the futuristic ultra-tech backdrops and extravagant filmic flourishes, and rather interested in human relationships plus the human-machine relationships. The film doesn’t seem much initially. It gives off a feeling of being a very talky picture or filmed play that’s amateurish in its conception. But our misgivings are soon overturned. For one, the dialogue doesn’t always try to explicate its themes and then the four central performers are absolutely great. Almeredya and gifted cinematographer Sean Price Williams (Queen of Earth, Heaven Knows What, Good Time) does their best to generate a visual rhythm and observes the vibrant spaces and faces in the manner that suits the medium, although they couldn’t fully free the narrative from its stage-bound nature. On hindsight, one must admire the duo for avoiding ostentatious visual flourishes and keeping things subtle (or minimal) which allows the contemplative ideas and wonderful performances to deeply take root.

The story is wholly set in a house by the beach whose inhabitants are: octogenarian widow and a former concert-violinist Marjorie (Lois Smith), her daughter Tess (Geena Davis), Tess’ husband Jon (Tim Robbins), and a live-in caregiver Julie (Stephanie Andujar). The film opens with the shot of Marjorie gazing at the sea. She walks inside the empty living room and when she sits in a recliner, a middle-aged man, appears out of nowhere, sitting opposite her. The man (Jon Hamm) is a slightly younger version of Marjorie’s dead husband Walter and he is not the result of the old woman’s schizophrenia. He is a perfect hologrammatic replica (otherwise known as Prime) of Walter in his 40s (Marjorie wants to remember her husband like this) who is meant to provide companionship for Marjorie as she is gradually losing her mind to dementia. The interesting aspect about the Prime is that people must recall their own memories to build up the brain of the Prime and further assist them with future exchanges. Jon and Marjorie, in her good days, feed the Prime with their memories, regardless of its truthfulness. Holo-Walter or Walter Prime reiterates it later in the form of a coherent narrative whenever the old woman lacks company or fishes for a memory.

The opening exchanges are brilliantly written which exposes the machines lack of consciousness and presence of a peculiar self-seriousness. The Prime takes every word literally (as when Marjorie playfully calls it ‘idiot’ the hologram wears a glum expression) devoid of the idiosyncrasies and playfulness that define our conversations. However, the Prime quickly soaks up all such nuances and replicates it later. The opening scene also establishes the central theme or the paradox of the narrative: on how we exoticize our fonder memories in a way that makes it less truthful every time we recall it. Furthermore, the Prime stands-in as the perfect, elaborate metaphor of our social media. The Prime isn’t a mere simulation but a mirror which reflects our selective memory, pretty much like our well-adorned ‘wall’. This idea is reflected when Walter Prime tells the story of the 1997 movie My Best Friend’s Wedding, in a self-effacing manner, which was actually their date movie and after its ending Walter proposed marriage to Marjorie. Old Marjorie doesn’t remember that and she wonders if wouldn’t it be more romantic to say they watched ‘Casablanca, in an old movie theater with velvet seats’. Tess is totally skeptic of the Prime and finds the whole idea ‘creepy’. She has always remained estranged from her mother, especially after the suicide of her elder brother Damien, whose name is advised to not be uttered in the presence of Marjorie. Tess also has a shaky relationship with her own daughter Raina. The whole painful nature of their existence and frayed relationship only comes to light in the human-to-human conversations. Although life in general is unpredictable or unfathomable, we can choose the memories – however tenuous it might be — to create a portrait of us. In a part disquieting and fascinatingly low-key manner, the film showcases how that future would look like when undying machines exist, burdened by the idealized memories of each other.

Director Michael Almeredya overtly pays tribute to Alain Resnais’ confounding masterpiece Last Year at Marienbad (in the scene Jon and Tess kiss in front of a vast mural at a European museum) and Ingmar Bergman’s Autumn Sonata (about a similarly distressful relationship between mother and daughter). As I mentioned earlier, both Almeredya and DP Sean Williams does their best to cinematically reconceive the play. There are calm shots of the ocean which puts a metaphorical spin on the story and there’s clever inclusion of brief, less-talky flashbacks to inquire upon the unreliability of memory. Apart from the ‘hall of mirrors’ element Tess talks about (the quote mentioned above), Almeredya approaches the question of memory without turning it into a thesis yet keeping intact the complex, esoteric notions surrounding it. In one scene, Tess talks about a girl’s parrot which keeps talking in her deceased father’s voice, even 20 years after. “Well, she says it’s not exactly his voice, but she can definitely tell that it’s him”, Tess states. It’s a simple line of dialogue yet deeply conveys the unbridgeable gap between our memory and truth or actuality. Much of the written dialogues and stagings are done in this manner that contains hidden depths beneath its simple surface [the final exchange between the three Primes was spellbinding].

Marjorie Prime may feel too gentle at times and would definitely disappoint those expecting a robust SF conceit. But as a non-traditional think-piece, it triumphantly gauges the ever-relevant ideas of memory and identity. The masterful committed performances from the cast perfectly brings alive the emotional quotient. Lois Smith reprises the role she played at the stage. Almeredya states his primary aim to make the film was to work with the veteran actress and the why is evident in Lois’ ethereal, genteel presence. Geena Davis and Tim Robbins fully use their chance to play a subtle role after a long time. The couple’s self-doubt and hidden vulnerability broadens the narrative’s emotional canvas. Hamm, who also shares a executive producer credit, ably portrays the Prime with an affectless, deadpan dialogue delivery. Mica Levi’s (Under the Skin) musical score is another alluring aspect of the film which instills an extra-layer of soulful feelings.

Marjorie Prime (100 minutes) is an enticing chamber drama on our abiding and elusive relationship to memory. Despite a micro field of vision and pared directing style, the film perpetually digs deep into the characters and concepts so as to accelerate an internal dialogue on the part of the viewer.