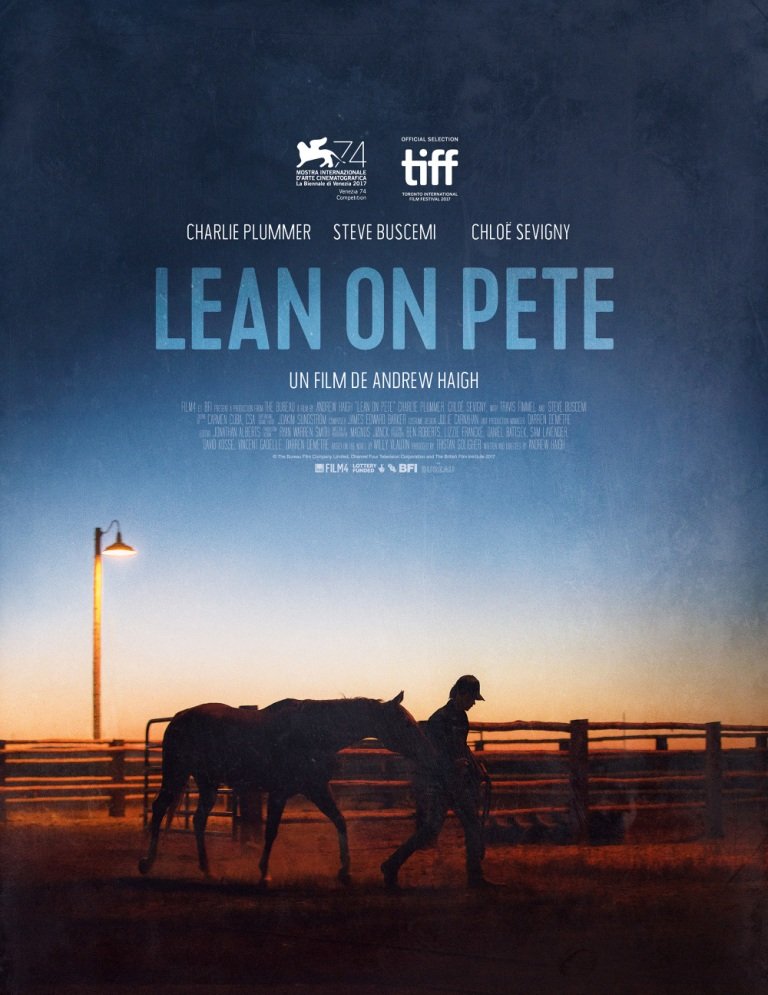

English film-maker Andrew Haigh’s previous devastating existential dramas – Weekend (2011) & 45 Years (2015) – were essentially about lonely souls desperately yearning for companionship (or love) so as not to feel alone. What Mr. Haigh excels in is showcasing the lonesomeness of people through an ultra-nuanced, non-melodramatic approach. There’s a sense of grief and pervasive loss diffused throughout his narrative, yet it doesn’t become outright depressing or unrealistic. With Lean on Pete (2017), adapted from Willy Vlautin’s novel, Andrew Haigh once again tells a splendidly low-key tale of a bereft soul, cast adrift in the Land of Opportunity & Dreams. Lean on Pete’s posters might make it seem like an inspirational coming-of-age tale about a boy and his (pet) horse. But this quiet drama that traces a gangly teenager’s arduous journey through the wastelands and impoverished quarters of America doesn’t contain the feel-good tone of horse-themed movies, The Black Stallion (1979) or Sea Biscuit (2003). Haigh’s movie rather gleans a bit from novelist John Steinback’s gritty miserabilism and film-maker Robert Bresson’s austere vision. Hence the melancholia surges through the central connection between an adolescent and an animal reminds more of Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) and Kes (1969).

Fifteen year Old Charley Thompson (Charlie Plummer) has recently moved to Portland, Oregon with his deadbeat but affectionate father Ray (Travis Kimmel). Charley’s existential scars are gracefully divulged: mother is absent (ran away) and he hasn’t seen his beloved aunt Margy (Alison Elliott) for years due to his father’s squabble with her. But Charley is a sweet boy. His sunken eyes and gaunt face lights up at every possibility of finding love or at least a stable family life. He also easily trusts others. Charley loves running and finds out that their shack is situated near a racetrack. Charley was on the verge of getting accepted into the football team of his Wyoming high school when his dad moved out here. Now his curiosity is piqued by the racetrack horses. By chance, he meets Del (Steve Buscemi), a grizzled old guy who races quarter horses, and instantly accepts the offer to work with him at the stable. Charley also travels with Del to country-fair circuits & backwoods race tracks, and all the while the teenager grows to love and care for mellow 5-year old quarter horse named ‘Lean on Pete’. ‘Don’t get attached to the horses’, warns Del, but it’s hard for Charley to not get swept away by the fresh wide-world and under-sung Pete.

While Andrew Haigh’s ’45 Years’ and ‘Weekend’ were sterling character studies that enhanced the characters’ silent introspection through the passive gaze upon beautiful landscapes, Lean on Pete serve as both a character and social study. Haigh doesn’t perfectly adjust to this kind of storytelling, as he seems to struggle a bit with the heightened drama, especially in the narrative’s sprawling desert-set second-act. Yet Haigh and his Danish cinematographer Magnus Nordenhof Joenck (‘A Hijacking’, ‘A War’) firmly places the protagonist into this specific context, exhibiting the ugly and blistering dimensions of American dream. Similar to the works of Werner Herzog (‘Stroszek’), Kelly Reichardt (‘Wendy & Lucy’), Andrea Arnold (‘American Honey’), etc through the camera’s crave for the picturesque wide-open spaces of United States, the downcast, dispossessed state of its citizens is highlighted with tragic irony. Most recently, Sean Baker used garish, half-decayed structures of Florida to portray the incredible tragedy of underprivileged kids (‘The Florida Project). Of course, Lean On Pete isn’t preoccupied to go for a politically relevant depiction of Trump’s America. The indictment of unsavory American values here is more abstract since Haigh’s intimate focus mostly lies on the vulnerable yet self-determined teenager’s rite-of-passage.

Except for the bland exposition techniques employed in sequences where Charley addresses the horse (revealing his inner thoughts), Andrew Haigh develops the story-line organically and subtly. The novel’s attempt to depict various culturally and socially ostracized people (group of dispirited veterans, nomadic homeless community, etc) appears a bit schematic, although Haigh doesn’t stage these scenes with notes of implausibility or pity. Haigh’s visual style often places Charley amidst the vastness of America’s landscape so as to depict how the vulnerable and prideful individual is consistently overwhelmed by the dispassionate society. Eventually, Lean on Pete may come a bit short in reaching the heights of masterful adolescent tales like 400 Blows or Kes, but it certainly takes forward Haigh’s talent for nuanced storytelling. Moreover, the performances are nothing short of astounding. Charlie Plummer’s measured acting style often substitutes dialogues with meaningful looks and subtle emotions. His restraint and solemnity keeps the film rooted amidst the barrage of sorrowful twists. And it’s hard to keep our own emotions at bay, when Plummer’s Charley finally breaks down at the end of his excruciating journey.

Lean on Pete (121 minutes) is an affecting coming-of-age tale which also casts an unsentimental gaze at poverty and hardship in America. It is an unexpectedly grim and heartrending look at the desire for acceptance and selfless love that drives one’s life.