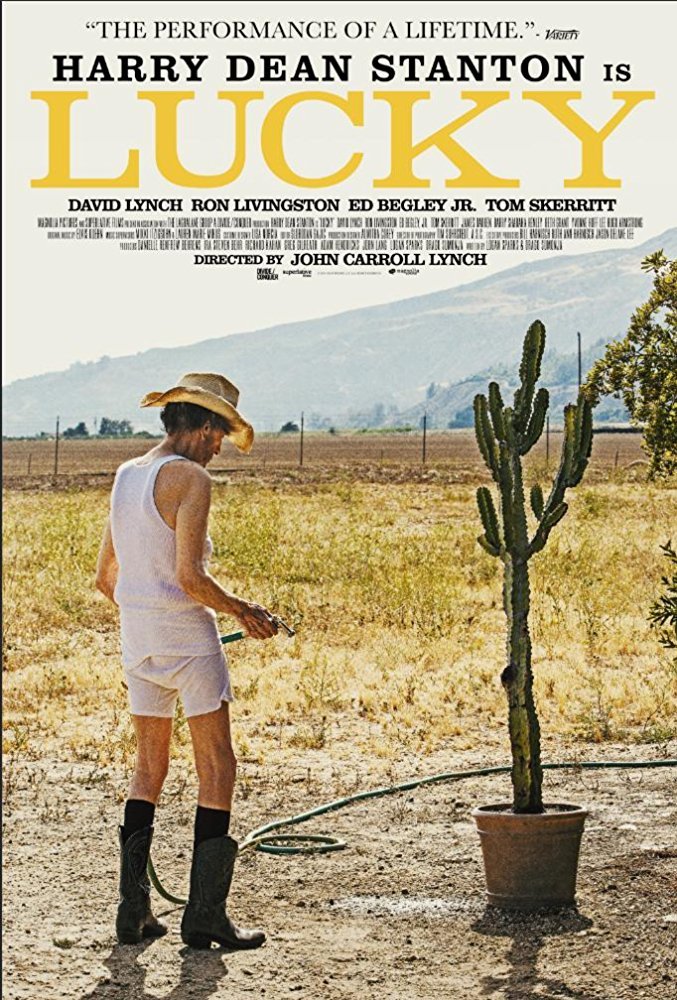

Lucky [2017]: A Gentle, Charming Tributary Piece to the Late Harry Dean Stanton

Harry Dean Stanton, the legendary actor & hipster icon with dead pan voice, wiry figure and craggy face, has been known for his perennial and memorable presence in TV, independent and cult American cinema. A spectacular character artist in his own right, Stanton tackled numerous roles, irrespective of the length of his screen-time. The actor’s prolific six-decade plus career (appeared first in a TV role in 1954) has gained richly deserved attention in the recent years. One of Harry Dean Stanton’s fine accomplishments is his refusal to plunge down sentimentality yet diffusing feelings of sensitivity and fascination. From playing guitar-wielding convict in Cool Hand Luke (1967), a hitchhiker in Monte Hellman’s cult road-movie Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) to his cameos in The Straight Story (1999) and The Avengers (2012), Stanton has been the mainstay of American indie/Hollywood circuit. David Lynch, Coppola, and Jack Nicholson were Stanton’s close friends, and famous critic Roger Ebert, once mused “no movie featuring either Harry Dean Stanton or M. Emmet Walsh in a supporting role can be altogether bad” (although Ebert later admitted that 1989 movie ‘Dream a Little Dream’ was an exception to this). The actor died in September 15, 2017 which can’t be termed as shocking, given that he is aged 91. Moreover, his swan song or inadvertent eulogy Lucky (2017) perfectly serves as a first-rate showcase of the actor’s unpretentious personality. Despite being plot-less, Lucky’s metaphysical layers and meditation on mortality, existence gains more profundity, knowing that Stanton no longer exists (the film released two weeks after Stanton’s death).

Harry Dean Stanton plays Lucky (or as one could say, he is lucky), a taciturn but a decent cowboy-hat-wearing old guy with a chain-smoking habit. First-time screenwriter Logan Sparks and Drago Sumonja reportedly conceived the project with Stanton in mind and the philosophically heavy material wouldn’t have been this remarkable, if the actor had said ‘No’. Prolific actor John Caroll Lynch (Fargo, The Good Girl, Zodiac, etc) has made his directorial debut with Lucky, who doesn’t affect the narrative and the veteran performers’ nuance. Stanton’s Lucky lives alone in a small, ram-shackled New Mexico town. The film depicts his routine life over the course of few consecutive days (a structure that reminds us of Jarmusch’s Paterson). He wakes up, does some quick yoga exercises, and smokes cigarettes. He opens the fridge, where there is only milk; a life pared down to essentials. Later, he walks to the diner for coffee, doing crossword puzzles and has a mix of good chat with the old friend/diner owner (Barry Shabaka Henley, who played the bar owner role in Paterson), waitresses and other customers. He buys milk and cigarettes from a local convenience store, heads back home for watching the game show. In the evening, he walks to the local bar, meeting other local regulars (played by Beth Grant, James Darren, and David Lynch).

One day, Lucky keels over, while preparing coffee and goes to the hospital. The physician (Ed Begley Jr.) doesn’t find anything wrong and gives him the routine advice that cigarettes are going to kill him. Lucky casually dismisses the notion by saying: “If they could have, they would have”. Occasionally, Lucky is subjected to moments of existential dread and philosophical clarity. He routinely exchanges his distinct greeting, “you’re nothing” to his friend, ruminates that ‘Realism is a thing’, and has weird encounters with a life insurance salesman (Ron Livingston), a brooding ex-Marine (Tom Skerritt), which makes him expressly come to terms with the inevitability of death. But, Lucky also discovers he isn’t as isolated or uncared for like he thought. Finally, when he drops his ‘everything goes away into blackness, void’ speech to the intently listening oldies at the bar, they ask “What are we supposed to do with that?” He replies, “You smile”. And, that’s exactly what we do at the film’s eventual fade to black-screen; we smile at the legendary actor’s steadfast, stoic resilience. As for smiling at the unknown, uncanny, empty, repetitive dimensions of life, I ain’t still wise enough.

Director John Lynch and screenwriting pair Sparks-Sumonja makes it pretty clear that Stanton is playing a character fully attuned to his temperament. This factor brings chief magnetic force to the narrative. Furthermore, it’s good that the screen-writers don’t use the actor’s persona for weaving a mawkish plot trajectory. Stanton’s Lucky doesn’t befriend an alienated teenager or rejuvenate his romantic life, even though there’s tinge of sentimentality in the way the townspeople view Lucky with reverence and adoration. The film isn’t exactly a profound reflection of the existential anxieties of the American elderly people. Some of the confrontations push up the thematic notions in an unsubtle manner. Yet as a soulful tribute and farewell to the unorthodox Stanton, Lucky largely succeeds. There are certain scenes that thickly lay out the ideas of mortality. But, John Lynch’s direction of the actors brings a quiet, lyrical quality to the proceedings, adding more textures to the simple exchanges. For example, the recital of ex-marine’s gruesome war experiences (about a little girl who smiled at the brink of death and destruction) unsubtly draws parallels to Lucky’s own quandaries over death. But Tom Skerritt delivers the feelings of misery and guilt in a powerfully subdued manner which brings more depth to the scene. The same could be said for the astoundingly emotional sequence when David Lynch delivers an earnest speech about letting-go his old beloved pet, a tortoise named ‘President Roosevelt’.

Sparks & Sumonja’s script walks a tight-rope between profundity and insipidness, while John Caroll Lynch’s patient direction smooths-out the uneven qualities of the character study. Nevertheless, the chief pleasure lies is savoring Stanton’s underplayed performance. There’s something soothing about witnessing Stanton strolling through dry, arid lands, like in Wim Wenders’ masterpiece Paris, Texas (1984). The script derives many of the protagonist’s character sketches from Stanton’s own life (unmarried status, working as a cook in navy during WWII, etc). Among the best showpiece acting part of the narrative, my favorite is when Lucky performs a quavering rendition of a Mexican folk song at a kid’s birthday. It’s a beautiful scene where the actor initially stands as an isolated figure in the party, and through the singing routine he understands his connectedness. Stanton’s subdued expression in this scene stands as a microcosm of Lucky’s whole subtle, interior journey towards the acceptance of mortality. All the other supporting performances imbue cherishable moments to the proceedings, the chief being legendary director David Lynch’s character Howard. “I miss my friend, his company. I miss his personality. You know what I’m saying? He affected me”, says the character played by Lynch who, is passionately talking about his lost tortoise. The words could, however, also stand as eulogy stating Lynch’s long friendship with Stanton, who had the perseverance and grit of a long-living tortoise.

Lucky (88 minutes) is a hushed-up and slightly uneven character study of an unorthodox 90 year old small-town American, which gains immense mileage out of codgy, unsentimental force radiated by favorite cult actor Harry Dean Stanton. It’s a poignant, metaphysical gaze at an old guy, skirting through the edges of mortality with a smile on his face.