Legendary film-maker Agnes Varda, a major figure of the French New Wave who turns 90 this May, recently took home the honorary Oscar. In an interview (with Bomb magazine), when asked about her thoughts on this Oscar, she told that it’s a ‘big honor and a joke’. Joke because “they give Oscars to famous people because they make money for the producer. That’s why I don’t get a normal Oscar. I get a secondary type. They think I deserve something, but I am not part of the big world of money. I am known, but I am not successful.” Ms. Varda’s distinctive experimental style, documentary realism, and greater humanist purpose may not have always gleaned her success or popularity, but this compassionate grandma of cinema seems to be the perfect embodiment of emboldened artist. In her six decade-plus movie career, Varda has aimed to reinvent herself with every new project. She has entranced us with classics like “Cleo from 5 to 7” and “Vagabond”, and in the past two decades she has tried to find new forms of storytelling by fully embracing the documentary medium. Her intimate, first-person account of journey across the French countryside in “Gleaners and I” (2000) and autobiographical work “The Beaches of Agnes” (2008) profoundly focused on the themes of community, life, grief, and the meaning of memory. Agnes Varda’s new collaborative work with young street artist/photographer JR titled Faces Places (‘Visages Villages’, 2017) once again employs deeply humane artistic expression to confront the incontestable notions of mortality, death, and social evolution.

Part of the charm in Varda’s passionate documentaries lies in witnessing her positively infectious mood, her adoration for cinema, and other playful shenanigans. Her curious, cross-country jaunts oft give the feeling of hitting the road with a trusted friend. With Faces Places, the enthusiasm is only doubled up due to presence of JR, who possesses the lithe, ecstatic spirit of an artist. What kind of a movie is Faces Places? Considering the talks that this might be Varda’s last project, can we count it as a work saying farewell? Or is it simply a prankish, improvised art installation that’s also a matter-of-fact-meditation on communal living and nobility of the common man? Or is it a subtle portrait of inter-generational friendship? May be it’s a buddy road trip comedy. Faces Places is all of these and much more; a testament to Varda’s artistic grit and most importantly a deft inquiry into memory and images, and how it shapes our life force.

During the trip to a placid French village, they line up the locals and take their individual portraits, asking them to hold a baguette in front of the face. Eventually the large, individual portraits are glued together in a row to create the illusion of them all holding one long baguette. At one point, Varda muses, “JR is fulfilling my greatest desire. To meet new faces, and photograph them, so they don’t fall down the holes in my memory.” Gradually the projects, not only becomes a means to celebrate the shared happiness of communal living, but also a personal endeavor for Varda as she contemplates the varying spectrum of her own mortal experiences. While JR and his able-bodied team handle the photography and its creative development, Varda glimpses into others’ lives, asking warmly humanist questions. She meets assortment of fascinating people from different walks of life: a shy café waitress whose giant portrait attracts lot of onlookers; a young small-town bell-ringer; an old village eccentric with chipped tooth leading to his elaborately decorated shack in the woods; a cheese-making couple who doesn’t burn their goats’ horns; and finally the wives of dockworkers in Le Havre. And, all these encounters are full of immutable joys, humane gestures, and deep reflection.

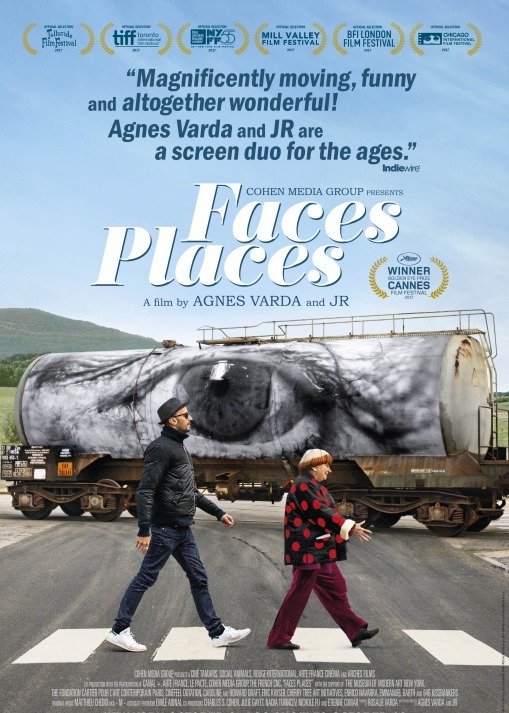

Agnes Varda with her mischievous eyes and trademark two-tone hair-style, and tall JR, an amiable yet enigmatic artist always wearing a dark sun-glass, are the delightful nomadic pair. The vibe between them happens to be the documentary’s perennial source of pleasure. The relationship between Varda and JR ranges from bickering pals, like-minded artists, teacher and student, and colleagues. Early on Varda explains that JR’s sunglasses and recalcitrant refusal to remove them reminds her of Jean-Luc Godard, who also sported a sun-glass and Varda pressed him to remove them during a short film (in 1961), which he eventually did. In fact, JR’s obstinacy to take his glasses off becomes a running joke in the movie, one that hits a poignant note during the ending. Faces Places also subtly wades into the personal lives of the co-directors/artists. At one spirited occasion, Varda goes to visit JR’s 100 year old grandmother. Later, we see medical procedure subjected to Varda’s eyes to treat her disease, which is causing gradual blindness. After the procedure, she jokingly remarks how it made her think of Un Chien Andalou’s infamous eye-slashing shot. The scene also has a touching dimension as it laments for the loss of Varda’s personal sight and its magnanimous power to make exquisite images. The pair talks more about death and accepts its inevitability, as they visit a small cemetery where great photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck are buried. On an enrapturing note, we see JR pushes Varda in a wheelchair through the Louvre, in an effort to recreate the iconic scene from Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964).

Since Varda’s personal recollections and general reflections often brings up the personality of Godard, it seems only right to conclude the journey with the film-makers meeting the iconic director. The trip to meet the ever-elusive Godard only brings to surface painful emotions for Varda (he agrees to meet them, but only to shun them with a cryptic, coded message). The narrative trajectory of the documentary is slightly changed. The well-packaged happy ending is missing. Earlier on, Ms. Varda says that “chance has always been her best assistant”. Hence she quickly resolves (choking back tears) from this devilish, inhospitable behavior (of Godard) and JR broods upon how this planned visit is a reflection of the artist’s compulsion to make their work seem complete. The planned visit may have gone astray, but Agnes Varda clings to the chances she gets and harvests pure emotions out of it. Faces Places (89 minutes) may be incomplete in one sense, but it also remains as a genuinely exceptional (uncategorizable) piece of film-making. It’s a soulful observation on the ineradicable synergy between the works of art and everyday life.